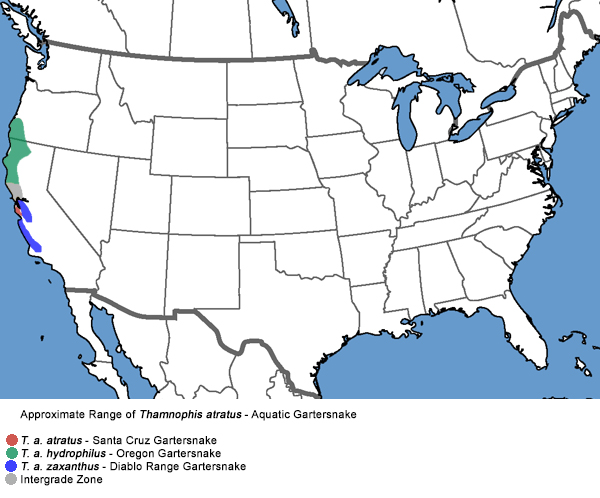

Aquatic Gartersnake - Thamnophis atratus

Diablo Range Gartersnake - Thamnophis atratus zaxanthus

Boundy, 1999Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

Light Blue: Range of this subspecies in California

Light Blue: Range of this subspecies in CaliforniaThamnophis atratus zaxanthus - Diablo Range Gartersnake

Range of other subspecies in California:

Red: Thamnophis atratus atratus - Santa Cruz Gartersnake

Orange: Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus - Oregon Gartersnake

Gray: Aquatic Gartersnakes formerly recognized as

the subspecies Thamnophis atratus aquaticus,

now recognized as an area of intergradation

between the three recognized subspecies.

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Contra Costa County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Contra Costa County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Contra Costa County | Adult, Contra Costa County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Contra Costa County | Adult in shallow water, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Contra Costa County | Adult, Contra Costa County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Ryan Sikola This species is so rare at the edge of its range in San Luis Obispo and Santa Babara counties that it will breed with the more common Two-striped Gartersnake. See "Hybrids" below. |

Adult, Alameda County © Adam Clause |

Adult, Alameda County © Yuval Helfman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult with bright yellow coloring, San Luis Obispo County © Joel Germond | Adult, Monterey County © Benjamin German |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile and hatchling pond turtles basking next to a Diablo Range Gartersnake in a Contra Costa County pond. © Mark Gary |

Adult, Alameda County © Faris K | Adult, Monterey County © Regan Sikola |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Clara County © Zachary Lim |

This snake was found at the supposed edge of the range of the subspecies, in Newman, Stanislaus County © Gary Cline. This made me wonder if that really is the edge of the range. If they are found in Newman, which is on the valley floor, I see no apparent reason why Diablo Range Gartersnakes cannot survive farther east into the valley anywhere along their range. If you have seen one outside the range shown on my map, please let me know. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Contra Costa County | Neonate, late August, Contra Costa County |

Juvenile, Contra Costa County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult eating a Bullfrog tadpole in Santa Clara County. © Chad Lane |

Janet heard squeaking then saw a gartersnake rolling and twisting down an incline. When they stopped, the snake was the victor in a struggle with a vole. Solano County. © Janet Ellis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult eating a frog (possibly a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog) at the edge of a creek in Santa Clara County © Douglas Brown | An intergrade Aquatic Gartersnake in Napa County eats a frog (either a California Red-legged Frog or a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog.) © Pamela Delgado | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This series shows a Diablo Range Gartersnake eating a California Tiger Salamander larva in Contra Costa County. The snake caught the larva in the water, then brought it to shore to swallow it. © Mark Gary |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This Diablo Range Gartersnake was observed in October eating a toxic California Newt in Alameda County at the edge of a newt breeding pond. You can see the snake biting the tail, then swallowing the newt tail first and then the head. You can read about gartersnakes eating toxic newts here. © Mark Gary |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This tiny juvenile Diablo Range Gartersnake was observed in December eating a recently-transformed juvenile California Newt on the edge of the same newt breeding pond in Alameda County where the adult snake above was observed eating an adult newt. © Mark Gary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diablo Range Gartersnake eating a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog in Santa Clara County © Zachary Lim | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hybrids | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Barbara County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Ryan Sikola |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| These snake are unusual hybrids of the Diablo Range Gartersnake and the Two-striped Gartersnake, Thamnophis hammondii. Note the thin yellow vertebral stripe that is not present on T. hammondii and is much thinner than that found on T. atratus. T. atratus is so scarce at the edge of its range in San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties that they breed with T. hammondii which is more abundant in the area. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intergrades | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult intergrade, Marin County | Adult intergrade, Marin County | Adult intergrade, Marin County | Possible T. a. atratus x T. a. zaxanthus intergrade adult, Santa Clara County © Jared Heald |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| North of the San Francisco Bay, there is a very large intergrade range mixing the subspecies T. a. hydrophilus, T. a. atratus, and T. a. zaxanthus. The snakes in this area were formerly classified as T. a. aquaticus (previously T. couchii aquaticus( but this subspecies is no longer recognized. More pictures and information about these intergrades can be seen here. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, spring, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, spring, Contra Costa County | Habitat, Alameda County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, small pond, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, summer, Contra Costa County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Alameda County |

Habitat, Alameda County | Habitat, 500 ft, western Stanislaus County |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diablo Range Gartersnakes in and around a small cattle pond in Contra Costa County. | Diablo Range Gartersnakes swimming in a cattle pond in Contra Costa County. | When it is picked up, a big adult Diablo Range Gartersnake demonstrates how it smears foul-smelling fluids from its cloaca all over the hand of its tormentor. Too bad they haven't invented online video with smells yet.... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -