|

|

|

|

| Adult found very close to the coast in Santa Barbara County © Max Roberts |

Adult, American Basin, Sacramento County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, 4,000 ft., Klamath Basin, Siskiyou County |

Adult, Plumas County |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Sierra Nevada foothills,

Calaveras County

|

Adult, San Benito County. |

Adult, 4,000 ft., Sierra County

© John Stephenson |

Adult, Butte County

© Jackson Shedd |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, northern Humboldt County |

Adult, Fresno County © Patrick Briggs |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron

|

Large, gravid adult female about 45 inches in length, Stanislaus County

© Adam Gitmed |

Adult, Butte County © Marcus Rehrman |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Napa County © Jonathan Koehler

This snake was found along the Napa River south of Yountville, which is close to where the T. s. infernalis subspecies meets the T. s. fitchi subspecies in Napa County. It looks more like T. s. infernalis to my eye, but some might call it an intergrade due to the fact that the entire head is not red. |

Adult, Fresno County © Brett Burch |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Santa Barbara County

© Ryan Sikola

|

Juvenile, coastal San Luis Obispo County, just north of the Santa Barbara County line.

|

Adult with faint red markings, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond |

This snake looks a lot like a Red-sided Gartersnake except that it has no red coloring on its head. It was observed a few miles from the ocean in San Luis Obispo County. © Brian Hubbs |

|

|

|

|

Adult, 6,500 ft. Siskiyou County

© Ryan Aberg |

Adult, Modoc County © Max Roberts |

Adult, Modoc County © Max Roberts |

|

|

|

|

Top: Mountain Gartersnake

Bottom: Valley Gartersnake

Both adults from Modoc County

© Max Roberts |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County

© Ryan Sikola |

Adult, approx. 9,000 ft. elevation,

Shasta County © Kurt Geiger |

Adult, southern Monterey County

© Laura Ann Eliassen |

|

|

|

|

| This snake from extreme southern Solano County appears to be mix of a Valley Gartersnake and a California red-sided Gartersnake. © Andre Giraldi |

Adult, Santa Barbara County.

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg

(Snake found by Andrew Louros of USGS)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Unusual Colors or Patterns |

|

|

|

|

| Melanistic adult, Yolo County © Richard Porter |

|

|

|

|

This very unusually-colored aberrant Valley Gartersnake was found in the Sacramento Valley in Sutter County, CA in May, 2017, and other snakes with similar coloring were seen in the same general field location, including the snake seen in photos below left.

U.S. Geological Survey photos taken by Alexandria M. Fulton.

(A Natural History Note about this snake was published in June, 2018: Herpetological Review 49(2), 2018.)

|

|

|

|

|

This aberrant Valley Gartersnake was photographed in 2016 in the Sacramento Valley in Sutter County, CA approx.1.5 km from the location where the snake seen above was found.

U.S. Geological Survey photos taken by Chris Garbark. |

This unusually-colored adult was found eating a California Toad in Upper Lake, Lake County. Possibly axanthic (missing red pigment) it might also represent an intergrade with T. s. infernalis, which sometimes has blue coloring.

© Yuri Brezinger |

|

|

|

|

This Valley Gartersnake with blue coloring was found in San Benito County near Hollister, which is not far from a population of California Red-sided Gartersnakes with similar blue coloring.

© Brandon King |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Valley Gartersnakes From Outside California |

|

| Adult, Klickitat County, Washington |

|

|

|

|

Underside of adult,

Klickitat County, Washington |

Juvenile, Kittitas County, Washington

|

In some areas, Valley Gartersnakes overwinter in large groups. Here you can see a mass emergence of Valley Gartersnakes and Wandering Gartersnakes in early May, Lincoln County, Wyoming. © Leslie Schreiber |

Adult with considerable red coloring on the side of the head, Skagit County, Washington © Zachary Lim |

| |

|

|

|

| Identification Tip |

| |

|

|

| |

Looking at the top of the heads can help to identify these sympatric species on the north coast:

T. sirtalis - Common Gartersnake (Left) has a larger longer head with bigger eyes than T. ordinoides - Northwestern Gartersnake (Right.)

© Filip Tkaczyk

California Gartersnakes Identification Key |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Valley Gartersnakes Feeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adult Valley Gartersnake eating a Boreal Toad in Trinity County © Spencer Riffle

|

|

|

|

|

Adult snake eating a California Toad.

© Pamela Greer |

Adult Valley Gartersnake found attempting to eat a non-native leopard frog of unknown species in a suburban backyard in Fresno County. (The frog survived, but died later.)

© Stephanie Mastriano |

This unusually-colored adult was found eating a California Toad in Lake County.

© Yuri Brezinger |

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Trinity Mountains habitat,

5,800 ft., Siskiyou County |

Habitat, Yuba County |

Habitat, 4,000 ft., Klamath Basin,

eastern Siskiyou County |

Habitat, Yolo County © Richard Porter |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, agricultural canal,

Sacramento County |

Habitat, 400 ft., Butte County |

Habitat (with snake bottom left), southern Monterey County

© Laura Ann Eliassen |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| A Valley Gartersnake is discovered resting in the sun near the edge of a mountain pond which is still half-surrounded by snow. When I get too close, the snake races off, showing the speed with which this gartersnake can crawl and swim to safety. |

Valley Gartersnakes race over land and in water at a high-elevation pond in Siskiyou County. |

A Valley Gartersnake at a creek in the Plumas County mountains. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Description |

Not Dangerous - This snake may produce a mild venom that does not typically cause death or serious illness or injury in most humans, but its bite should be avoided.

Commonly described as "harmless" or "not poisonous" to indicate that its bite is not dangerous, but "not venomous" is more accurate since the venom is not dangerous. (A poisonous snake can hurt you if you eat it. A venomous snake can hurt you if it bites you.)

Long-considered non-venomous, discoveries in the early 2000s revealed that gartersnakes produce a mild venom that can be harmful to small prey but is not considered dangerous to most humans, although a bite may cause slight irritation and swelling around the puncture wound. Enlarged teeth at the rear of the mouth are thought to help spread the venom.

|

| Size |

Adults of this species measure 18 - 55 inches in length (46 - 140 cm), but the average size is under 36 inches (91 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized snake with a head barely wider than the neck and keeled dorsal scales.

The eyes are relatively large compared with other gartersnake species.

Some average scale counts:

7, occasionally 8, rarely 6 or 9, upper labial scales, often with black wedges.

10 lower labial scales.

The rear pair of chin shields are longer than the front.

Average of 19 scales at mid-body. |

| Color and Pattern |

The ground color is dark gray, black or brown.

The dorsal stripe is wide and yellowish, and there is a yellowish stripe along the bottom of each side.

The red on the sides of this Common Gartersnake are usually confined to the area just above the lateral stripes, in a single row, alternating with dark markings

The top of the head is dark - black, dark gray, or brownish. There is sometimes a bit of red on the sides of the head.

The underside is bluish gray, and it may become darker toward the tail, or may become paler. |

Key to Identifying California Gartersnake Species

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Primarily active during daylight.

A good swimmer.

Often escapes into water when threatened.

The species T. sirtalis is capable of activity at lower temperatures than other species of North American snake. |

| Defense |

| When first handled, typical of gartersnakes, this snake often releases cloacal contents and musk, and strikes. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats a wide variety of prey, including amphibians and their larvae, fish, birds, and their eggs, small mammals, reptiles, earthworms, slugs, and leeches.

Toxic Newts

This species is able to eat adult Pacific Newts (genus Taricha) which are deadly poisonous to most predators.

An arms race between T. sirtalis and the tetrodoxin poison contained in Taricha has been documented, with newt toxicity varying by location and snake resistance to the toxin also varying by location.

(Edmund D. Brodie III. Patterns, Process, and the Parable of the Coffeepot Incident: Arms Races Between Newts and Snakes from Landscapes to Molecules. From In the Light of Evolution: Essays from the Laboratory and Field edited by Jonathan Losos (Roberts and Company Publishers). 2010.)

The Bay Area is the Center of an Evolutionary Race Between Hungry Snakes and Toxic Newts.

by Anton Sorokin. Bay Nature, April 6, 2022

Gartersnakes Can Become Poisonous

There is evidence that when Common Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) eat Rough-skinned Newts (Taricha granulosa) they retain the deadly neurotoxin found in the skin of the newts called tetrodotoxin for several weeks, making the snakes poisonous (not venomous) to predators (such as birds or mammals) that eat the snakes. Since California Newts (Taricha torosa) also contain tetrodotoxin in their skin, and since gartersnake species other than T. sirtalis also eat newts, it is not unreasonable to conclude that any gartersnake that eats either species of newt is poisonous to predators.

Williams, Becky L.; Brodie, Edmund D. Jr.; Brodie, Edmund D. III (2004). "A Resistant Predator and Its Toxic Prey: Persistence of Newt Toxin Leads to Poisonous (Not Venomous) Snakes." Journal of Chemical Ecology. 30 (10): 1901–1919.) https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000045585.77875.09

|

| Reproduction |

Females are ovoviviparous. After mating with a male they carry the eggs internally until the young are born live.

According to *Rossman et al. 1996, although Fall mating has been observed, most mating occurs in the Spring and most data for the species suggest that offspring are born some time between midsummer and early Fall, with considerable variation among and within populations.

|

| Habitat |

Utilizes a wide variety of habitats - forests, mixed woodlands, grassland, chaparral, farmlands, often near ponds, marshes, or streams.

|

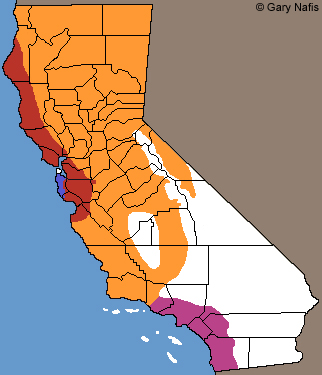

| Geographical Range |

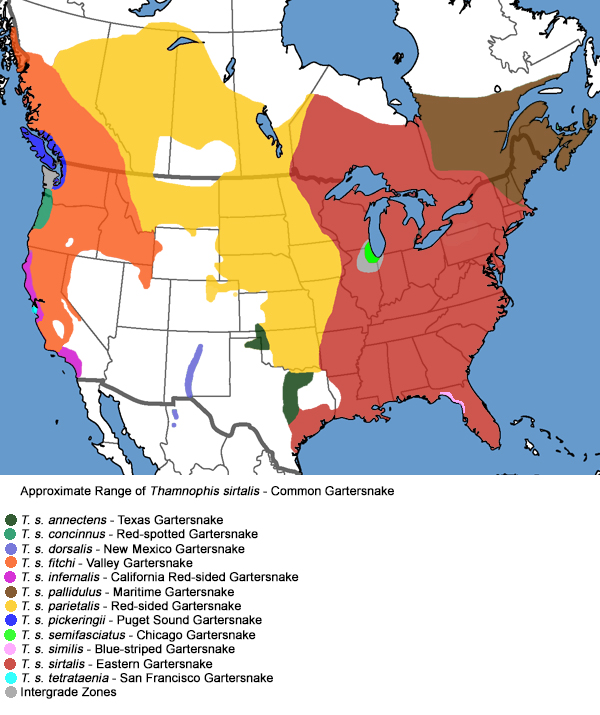

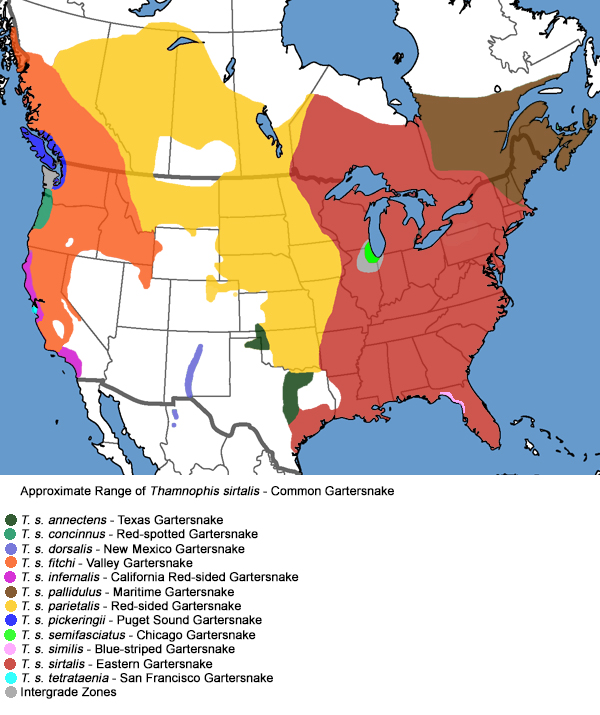

The species Thamnophis sirtalis - Common Gartersnake, has the largest distribution of any gartersnake, ranging from the east coast to the west coast and north into Canada, farther north than any other species of snake in North America.

This wide-ranging subspecies, Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi - Valley Gartersnake, is found throughout all of northern California, including the coast in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, south, east of the north and south coast ranges through the Great Valley and much of the Sierra Nevada (excluding a large part of the interior part of the San Joaquin Valley alley) and east of the Sierra Nevada into the northern part of the Owens Valley Outside of California. T. s. fitchi ranges north all the way to extreme southern Alaska, and east into western Nevada, Idaho, western Montana, western Wyoming, and north-central Utah.

(The western edge of the range of this subspecies as shown on my distribution maps is approximate and subject to change. For example: after I learned that an example of the infernalis subspecies was found on the east side of San Luis Reservoir in Merced County, I expanded its range east to cover that area. It's also possible there is a wide area of intergradation where both subspecies can be found. Researchers are no longer concerned with subspecies, so there is little information for me to go by.)

Uncertainty about which subspecies is present on the Central Coast between Monterey and Ventura Counties.

I have been uncertain about which subspecies is present in this area, T. s. infernalis or T. s. fitchi. Field guides show either one or the other in the area, but they don't show it as a range of intergradation where both subspecies can be found. I have heard from a reliable source that a respected herpetologist working in the area told him that the Common Gartersnakes within 5-10 miles of the Central Coast are T. s. infernalis, but I have not seen any pictures of them to confirm this. This picture shows a Common Gartersnake found 3 miles from the coast in San Luis Obispo County that has no red on the head, similar to T. s. fitchi. However, it also has large bright red spots on the sides that make it look more like T. s. infernalis, so it's possible the area near the coast is an intergrade area where snakes resembling either subspecies can be found.

Robert Stebbins, in his 1985, 2003, and 2018 western field guides, shows T. s. infernalis as the subspecies present along almost the entire coast with two areas in question in Ventura and Orange/San Diego counties. (His 2012 field guide does not show any subspecies of T. sirtalis.) My older range maps on this site showed

T. s. infernalis distributed along almost the entire coast, following Stebbins (and before the South Coast Gartersnake was recoginzed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife) but I changed it first to show intergrades on the Central Coast, then I changed it again to show only T. s. fitchi on the Central Coast for these reasons:

- Rossman et al. in The Garter Snakes - Evolution and Ecology 1996 * show T. s. fitchi as the subspecies present along the central coast from south of Monterey Bay to Santa Barbara County.

- In a 2002 study of western T. sirtalis, Janzen et al show T. s. fitchi as present in the area.

- A herpetologist who has surveyed the area told me that snakes in the area he has found have all keyed out to be T. s. fitchi - from the Salinas Valley south to Vandenburgh AFB in Santa Barbara County.

- I have seen several specimens from the area that were clearly T. s. fitchi, including one from right on the coast at San Simeon;

- All of the pictures of common gartersnakes in the area I have seen that can be identified look like T. s. fitchi, but none look like T. s. infernalis, including pictures I've looked at on iNaturalist and in the H.E.R.P. database. (Some are labled T. s. infernalis, but that is not evident from the pictures);

I don't have the resources to do a survey for snakes in the entire area or to check all of the museum specimens from the area, but until I see evidence that

T. s. infernalis also inhabits the area I'll show only T. s. fitchi, which I know is there. If you have seen pictures or other evidence of a snake that is clearly T. s. infernalis inhabiting the area, please let me know.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Rossman et al (1996) show the elevation record for the species (not specifically this subspecies) at 8,333 feet (2540 m.). Stebbins (2003) shows it as

8,000 ft. (2,438 m).

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 43, 2017 shows this note regarding the species Thamnophis sirtalis: "Analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear data suggest that this species may be composed of multiple independently evolving lineages often not concordant with the subspecific taxonomy (F. Burbrink, pers. comm.)."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Jones et al. (2023, Journal of Biogeography 50: 2012–2029) using genome-scale data did not find support for the traditional subspecies of T. sirtalis but rather discovered four distinct geographic lineages across North America. No taxonomic suggestions were indicated."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi - Valley Garter Snake (Stebbins 1966, 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi (Stebbins 1954)

Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis - Western Garter Snake (Coluber parietalis; Coluber infernalis; Eutaenia sirtalis obscura; Eutaenia sirtalis; Tropidonotus parietalis; Eutaenia proxima; Eutaenia imperialia; Eutaenia sirtalis pickeringii; Thamnophis infernalis, part; Thamnophis elegans, part; Eutaenia concinna; Thamnophis parietalis; Eutaenia sirtalis parietalis; Eutaenia sirtalis tetrataenia; Eutaenia sirtalis dorsalis. Pacific Garter Snake; Rocky Mountain Garter Snake; Red-barred Garter Snake; California Garter Snake; Churchill's Garter Snake; Dusky Garter Snake; Say's Garter Snake; Striped Snake; Pickering's Garter Snake) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Cascade garter snake

Northwestern garter snake

Pacific garter snake

Red-barred garter snake

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Colubridae |

Colubrids |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Thamnophis |

North American Gartersnakes |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

sirtalis |

Common Gartersnake |

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

Subspecies

|

fitchi |

Valley Gartersnake |

Fox, 1951 |

|

Original Description |

Thamnophis sirtalis - (Linnaeus, 1758) - Syst. Nat., 10th ed., Vol. 1, p. 222

Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi - Fox, 1951 - Copeia, p. 264

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Thamnophis - Greek - thamnos = shrub or bush + ophis = snake, serpent

sirtalis - Latin = like a garter - probably refers to the to striped pattern

fitchi - honors Fitch, Henry Sheldon

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

It is often reported that the name "garter snake" comes from the snake's striped back, which resembles the garters that were once used to hold up men's socks. In Etymology of garter snake evolutionary biologist Colin Purrington posits that "sirtalis" does not mean "like a garter" it means something closer to "ropelike." It follows that "garter snake" does not refer to the appearance of a man's garter, it is more likely "...a misspelling of guarder snake, garden snake, gardener snake, or garten snake."

|

|

Other California Gartersnakes |

T. a. atratus - Santa Cruz Gartersnake

T. a. hydrophilus - Oregon Gartersnake

T. a. zaxanthus - Diablo Range Gartersnake

T. couchii - Sierra Gartersnake

T. gigas - Giant Gartersnake

T. e. elegans - Mountain Gartersnake

T. e. terrestris - Coast Gartersnake

T. e. vagrans - Wandering Gartersnake

T. hammondii - Two-striped Gartersnake

T. m. marcianus - Marcy's Checkered Gartersnake

T. ordinoides - Northwestern Gartersnake

T. s. infernalis - California Red-sided Gartersnake

T. s. tetrataenia - San Francisco Gartersnake

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

* Rossman, Douglas A., Neil B, Ford, & Richard A. Siegel. The Garter Snakes - Evolution and Ecology. University of Oklahoma press, 1996.

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Snakes of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bartlett, R. D. & Alan Tennant. Snakes of North America - Western Region. Gulf Publishing Co., 2000.

Brown, Philip R. A Field Guide to Snakes of California. Gulf Publishing Co., 1997.

Ernst, Carl H., Evelyn M. Ernst, & Robert M. Corker. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003.

Taylor, Emily. California Snakes and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2024.

Wright, Albert Hazen & Anna Allen Wright. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1957.

Fredric J. Janzen, James G. Krenz, Tamara S. Haselkorn, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr, and Edmund D. Brodie, III. Molecular phylogeography of common garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) in western North America: implications for regional historic forces. Molecular Ecology (2002) 11, 1739-1751. © 2002 Blackwell Science Ltd

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|