Foothill Yellow-legged Frog - Rana boylii

Baird, 1854Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

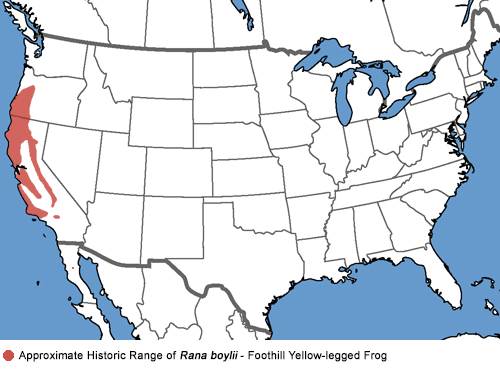

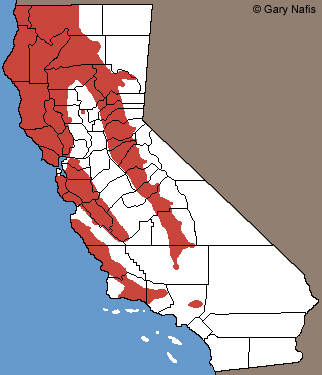

Red: Historic range in California

(No longer present in all these areas)

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Listen to this frog:

A short example

Volunteer for the Foothill Yellow-legged Frog Docent Program in Marin County with Marin Water: https://www.marinwater.org/VolunteerPrograms

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Mendocino County | Adult, Mendocino County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Clara County, showing the yellow under the legs that give the species its name. |

Adult in water, Trinity County | Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Clara County | Large old adult, Alameda County © Kevin Hintsa | Adult, Marin County © Zachary Lim |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult, Shasta County © Luke Talltree |

Adult, Butte County © 2005 Jackson Shedd |

Adult, Butte County © 2005 Jackson Shedd |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Marin County © Ben DeDominic | Adult in situ on a rock in a stream in Humboldt County © Spencer Riffle | Adult, Monterey County © David Hacker |

Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Marin County © Ben DeDominic | Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Placer County © Teejay O'Rear |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Yolo County © Teejay O'Rear | Adult, Yolo County © Teejay O'Rear | Adult, Nevada County © Teejay O'Rear |

Adult, Placer County © Teejay O'Rear |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Placer County © Zachary Cava | Underside of adult, showing the yellow under the legs. Linn County, Oregon | In-situ adults photogrphed during a permitted survey in Santa Cruz County © Zachary Lim |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A California Red-legged Frog and a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog in the same creek in Santa Clara County. © Owen Holt |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Foothill Yellow-legged Frogs With Unusual of Interesting Patterns or Coloring | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unusually-marked adult, Humboldt County © Nathan McCanne | Adult with mottled pattern, Shasta County © Michael A. Peters |

Red-backed form, Humboldt County © Steven Krause |

Red-backed form, Humboldt County © Steven Krause |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This very large adult photographed in Humboldt County appears to be missing dark pigment except in the eyes and it may be erythristic, with an excess of red pigment. © Kong Tran | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Del Norte County | Juvenile, Humboldt County | Juvenile, Del Norte County | Juvenile, Santa Clara County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile in water, Santa Clara County | Sub-adult, Shasta County © Michael A. Peters |

New metamorph, Santa Clara County © Neil Keung |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New metamorph, Santa Clara County © Neil Keung |

Sub-adult from Mariposa County © Christian Naventi |

New metamorph, Santa Clara County © Neil Keung |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-adult, Sonoma County creek. © egret.org / Audubon Canyon Ranch |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Yellow-legged Frog Eating | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wim de Groot captured this series of four pictures (the bottom two are enlargements) of a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog eating a fly in Santa Cruz County. We only see part of the large tongue that the frog is pulling back into its mouth here. The tongue was even larger when it was fully extended. © Wim de Groot |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diablo Range Gartersnake eating a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog in Santa Clara County © Zachary Lim | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of Rana boylii - Foothill Yellow-legged Frog with similar sympatric Rana aurora - Northern Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora is also similar in appearance to Rana draytonii - California Red-legged Frog which is sympatric with Rana boylii in much of its range.) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Left: Adult Rana aurora - Northern Red-legged Frog Right: Adult Rana boylii - Foothill Yellow-legged Frog Both frogs were found near each other in the same river in Linn County, Oregon. |

Top: Rana boylii Bottom: Rana aurora |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reproduction, Eggs, Tadpoles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male with paired vocal sacs not inflated (left) inflated (right) | Adult male and female in amplexus, Salmon River, Siskiyou County © Janjaap Dekker |

Adult Foothill Yellow-legged Frog in amplexus with an American Bullfrog in Nevada County © Tom Van Wagner | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Egg mass, Linn County, Oregon | Adult male and female in amplexus next to an egg mass in a Sonoma County creek. © egret.org / Audubon Canyon Ranch |

Tadpole, Santa Clara County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adults in amplexus, Marin County © Terry Goyan |

Adults in amplexus, Marin County © Terry Goyan |

Adult and egg mass in creek, Marin County © Terry Goyan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See More pictures of eggs and tadpoles and breeding habitat. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Mendocino County river |

Habitat, Mendocino County river |

Habitat, Del Norte County creek | Habitat, Santa Clara County creek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Santa Clara County creek | Habitat, Humboldt County creek | Habitat, Santa Clara County creek | Habitat, Stanislaus County creek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Shasta County creek © Michael A. Peters |

Habitat, 1600 ft., Del Norte County creek © Alan Barron |

Habitat, Shasta County river |

Habitat, Trinity County creek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, El Dorado County © Teejay ORear |

Habitat, Mariposa County © Christian Naventi |

Habitat, Humboldt County coast © Teejay ORear |

Habitat, Nevada County © Teejay ORear |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Mendocino County creek | Habitat, Placer County © Teejay ORear |

Habitat, Placer County © Teejay ORear |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scenes from a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog breeding site along a river in Oregon, including calls made in the air and underwater. (The underwater calls were not recorded along with the video, they were added later, however, the frogs depicted underwater are calling male frogs.) | A Foothill Yellow-legged frog calls at the edge of a small pool in a river with just its head out of the water, producing a call that can be heard in the air and underwater. The sounds heard here were recorded with an underwater microphone placed about 3 feet behind the frog. | Foothill Yellow-legged frogs trying to hide by blending in with the rocks on the bottoms of several creeks in California and southern Oregon. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Watch more short movies of this frog at Endangered Species International |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Six distinct population segments (DPS) of Rana boylii are recognized by state and federal agencies and each has its own conservation status. (See map above) I show the Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) listings from the January 2024 Special Animals List below. You can look at the most recent lists at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife CNDDB Plants and Animals page to see the status rankings of other organizations for each DPS: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals Population 1: North Coast DPS Population 2: North Feather DPS Population 3: North Sierra DPS Population 4: Central Coast DPS Population 5: South Sierra DPS Population 6: South Coast DPS |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | ||

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | ||

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | ||

| Bureau of Land Management | ||

| USDA Forest Service | ||

| IUCN | ||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -