Southwestern Pond Turtle - Actinemys pallida

(Seeliger 1945)= Southern Western Pond Turtle / Western Pond Turtle / Pacific Pond Turtle

= Emys marmorata pallida / Actinemys marmorata pallida / Clemmys marmorata pallida

Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

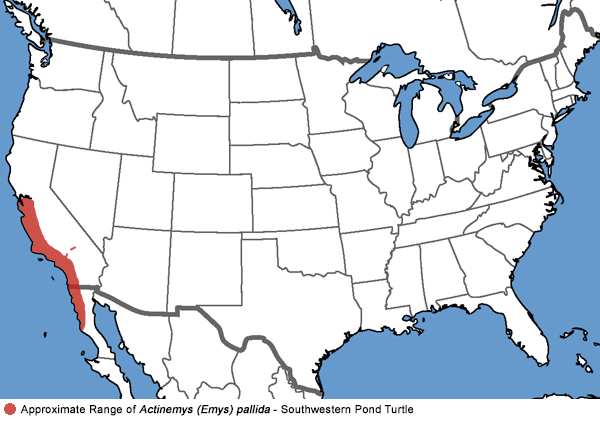

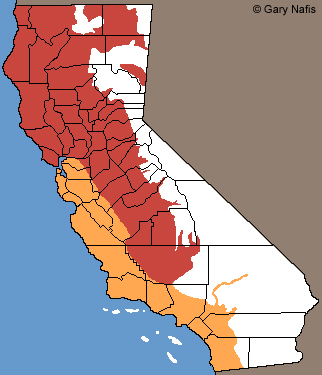

Orange: range of this species in California

Orange: range of this species in CaliforniaActinemys pallida - Southwestern Pond Turtle

Red: range of similar species

Actinemys marmorata - Northwestern Pond Turtle

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Volunteer to monitor Marin County Pond Turtles.

Training session, March 1st, 2025 with Marin Water:

https://www.marinwater.org/VolunteerPrograms

| Adults | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Santa Barbara County © Jason Butler |

Adult female, Santa Barbara County © Brian Hubbs |

Adult male, Ventura County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult male, San Luis Obispo Co., © Andrew Harmer |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Los Angeles County © Gregory Litiatco |

Adult, Santa Barbara County © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SCP or specific authorization from CDFW. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult turtle eating a juvenile crayfish, San Luis Obispo County © Brian Hubbs | Adult female, Los Angeles County © Gregory Litiatco |

Adults and juveniles, Los Angeles County © Jeff Ahrens | Adults and juveniles, Los Angeles County © Jeff Ahrens | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Brian Hubbs |

Adult in habitat, Santa Barbara County © Jason Butler |

Adults basking in February, Santa Barbara County. © Brian Hubbs | Young male, Orange County © Jason Jones |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Los Angeles County © James R. Buskirk | Adults, Monterey County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult with damage to its carapace, Orange County © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SPC or specific authorization from CDFW. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Monterey County © Kinji Hayashi |

Adult female, Monterey County © Kinji Hayashi |

Adult males, Riverside County © Brian Hubbs |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young adult, San Luis Obispo County. Some adult females, like this one, show a pattern on the neck similar to that seen on juvenile turtles. © Joel A. Germond | Adults basking at a creek in Ventura County © Brian Hubbs | Adult, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult and juvenile, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond | Adult and juvenile, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond | Adult and juvenile, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond | Adult, San Diego County © Andrew Borcher |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This San Luis Obispo County pond turtle was handled and released with permits by a licensed wildlife rehabilitation facility. © Joel A. Germond |

Adult female basking on a plastic garbage can, L.A. County © Brian Hubbs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| San Luis Obispo County © Ryan Sikola | Adult and two juveniles, San Luis Obispo County © Joel Germond | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southwestern Pond Turtles from east, and west of the San Francisco Bay, south to Monterey Bay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These turtles were previously identified as either unknown, Northwestern Pond Turtles, or intergrades with the Southwestern Pond Turtle which previously ranged south from the Monterey Bay area. The California Department Species of Special Concern Project range map labels them as Southwestern Pond Turtles, so I will do the same for now. You can see their map here. (See comment below.) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adults and juveniles, Alameda County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Contra Costa County, with pale throat characteristic of a male | Adult, Alameda County | Adult, Santa Clara County © Neil Keung |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female, Contra Costa County | Adult, Alameda County | Adult female, crossing a trail in late May, San Mateo County. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adults, Santa Clara County © Neil Keung |

Immature adult, Alameda County. Some immature adult females show a pattern on the neck similar to that seen on juvenile turtles. © James R. Buskirk | Adult male, San Mateo County | Basking adult male (left) and female (right), San Mateo County. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Four adult females basking, Alameda County | Adults showing their climbing ability, Alameda County © Mark Gary | Basking adult female, San Mateo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two adult turtles from Santa Clara County with shells covered with algae. © Cait Hutnik (You can see lots more of Cait's pictures of pond turtles here.) |

Adult, Diablo Range, Alameda County © Noah Morales |

Basking adult, San Mateo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This adult pond turtle in Contra Costa County has large patches of algae growing on its shell. © Mark Gary | Adult male (left) and adult female (right) Alameda County, © Mark Gary |

These turtles from the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles County all died during the 2015 drought. © Huck Triggs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Differences Between Males and Females (genus Actinemys) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Females usually have a pale throat mottled with dark markings. |

Adult female with mottled throat © Grayson Sandy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Males usually have a pale throat with no dark markings. |

Males have raised areas towards the rear of the head, as you can see on this male from Santa Clara County. © Brian Hubbs | Males have a slightly concave plastron Left: Male Right: Female © Pierre Fidenci |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hatchling, basking in situ, Los Angeles County © James R. Buskirk | Hatchling, Monterey County © Kinji Hayashi |

Hatchling, Orange County © Jason Jones |

Hatchling next to U.S. 25 cent coin (.955 inches [24.26 mm] in diameter) Riverside County © Paul Maier |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hatchling, Contra Costa County © Mark Gary | Juvenile and hatchling pond turtles basking next to a Diablo Range Gartersnake in a Contra Costa County pond. © Mark Gary |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These 2 turtles are neonate A. pallida. Both were found in early May, in different years in Alameda County. |

A "tiny juvenile" A. marmorata found in mid-June, San Mateo County. |

Hathling A. pallida, 7 May 2005, Alameda County. The shell shows the granular character of the natal scutes, or areolae, typical among hard-shelled turtles of all families, but only present on tiny juveniles during the spring months. © James R. Buskirk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hatchling, Contra Costa County, with a flesh fly on its carapace. © Mark Gary | This hatchling was found in early June in a Contra Costa County pond that was almost dried up. © Mark Gary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pond Turtle Tracking |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Santa Clara County turtles with transmitters attached to their shells. An antenna with a radio receiver that can find these transmitters is used to find the turtles and track their movement in order to study their behavior. Transmitters on females like the one on the far left are placed on the side of the shell to prevent obstacles to males during breeding. The transmitters are removed without damaging the shells when research is completed. © Neil Keung | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This Santa Clara County turtle travelled away from a dry creek in summer to bury itself in an upland location above the creek in oak woodland habitat where it will stay until the following Spring. The turtle was found by tracking the transmitter which you can see attached to its shell. © Neil Keung |

Find the turtles. Both of these adult pond turtles were tracked with radio receivers to where they were hiding in shallow creeks in Santa Clara County. Both are very well camouflaged and could easily be overlooked. © Neil Keung |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Pond Turtles Compared with Red-eared Sliders - Trachemys scripta elegans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The head, neck, and throat of the female Western Pond Turtle is mottled, with no red stripe behind the eye. | The head of the male Western Pond Turtle is dark with no red stripe behind the eye, and the throat is white. © Grayson B. Sandy |

There is usually a prominent red stripe behind the eye of the Red-eared Slider. | Some older or melanistic adult Red-eared Sliders do not have a red stripe behind the eye. © Will Kohn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

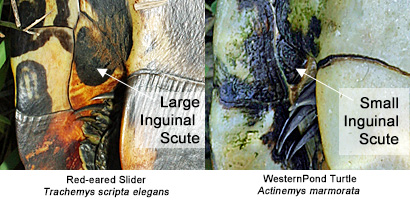

| A useful way to differentiate Western Pond Turtles from Red-eared Sliders, according to wildlife biologist Brandon Stidum, "...is to look at the marginal scutes 8-12 (...the scutes above the tail, or back scutes). Sliders have bifid or slightly forked scutes, where Western Pond Turtles do not; theirs are all smooth and do not split (except for traumatic injuries, but it’s usually only one or a few, not all scutes). The forking in the tail gives red-eared sliders the appearance that the tail is serrated or split in appearance. While looking for the presence and size of inguinal and axillary scutes is the best way to differentiate between the 2 once you have them in hand, a good way to do it from a distance is to look at the back scutes of the turtles." | Two adult Red-eared Sliders (left) compared with a much smaller adult Pacific Pond Turtle (right). © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SCP or specific authorization from CDFW. |

Ventral view of four adult Red-eared Sliders, with a much smaller adult Pacific Pond Turtle in the middle. © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SCP or specific authorization from CDFW. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identification Confusion with Melanistic Red-eared Sliders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melanistic adult Red-eared slider - Trachemys scripta elegans Riverside County. © Bob Parkard |

Melanistic adult Red-eared slider, (without red on the head) Riverside County © Bob Parkard |

Melanistic adult Red-eared with no red marks behind the eyes © Will Kohn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult Pond Turtle, Mendocino county | Adult female Pond Turtle © Grayson Sandy |

Adult male Pond Turtle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Click to enlarge |

Introduced melanistic sliders and old sliders whose red "ears" have faded, are often difficult to distinguish from the California native Western Pond Turtle, especially at a distance in the field, and even in hand. According to Bob Packard, with the Western Riverside County MSHCP Biological Monitoring Program, his organization confirms the identification of these turtles based on the presence of large inguinal and axillary scutes on the sliders, which are absent on the pond turtles (see illustration to the left) and by an interesting behavioral clue: the majority of sliders tend to be aggressive, biting readily, while pond turtles are far more reluctant to bite. You can also use the information described above about differentiating the two species from a distance by observing the rear marginal scutes, or back scutes. More pictures of melanistic sliders can be seen above. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

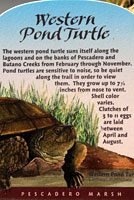

| Western Pond Turtle Eggs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These are pictures of the eggs of A. marmorata, which should be identical to those of this species, A. pallida. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Pond Turtle Eggs, © Patrick Briggs |

Western Pond Turtle Life Cycle: Adult, Juvenile, and Egg, Butte County. © The Chico Turtle Lab |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pond Turtle Feeding and Predation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult feeding on the carcass of a Bullhead Catfish in Santa Clara County. Several turtles were observed circling the dead catfish, tearing off pieces to eat. © Cait Hutnik |

This hatcling turtle was found in the stomach of an invasive bullfrog in Santa Clara County © Parsa Fard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Pond Turtles and Drought | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| © Mark Gary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Western Pond Turtles have evolved to live with ponds that dry up. As the picture above shows, the small pond shown below in the hills of Alameda County supports an extraordinarily high number of Western Pond Turtles - as many as 175 have been counted here. But in the fall of 2021 the pond dried up almost completely during a period of severe drought. Most of the turtles were gone in mid October when more than 20 of them were rescued and taken to the San Francisco Zoo. After winter rains re-filled the pond in the middle of March 2022 at least 87 live but emaciated turtles were counted at the pond. The rescued turtles had not been reintroduced yet which indicates that at least 87 turtles returned to the pond on their own. They most likely walked away from the pond and spent the winter buried in soil or leaf litter and then returned before mid March. It's possible even more will return. It's also possible that the pond will dry up again this year if drought conditions continue. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The pond completely full in March 2010, a year with plenty of rain. | The full pond from a distance in March, 2011, another non-drought year. | © Mark Gary The pond level has declined considerably in early September 2021, a severe drought year. 151 turtle noses and carapaces were counted in the water that remained. |

© Mark Gary One month later in early October 2021, the water level of the pond is still declining. Only 46 turtles were counted. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| © Mark Gary In mid October 2021 the pond is almost completely dry with only a few turtles remaining. More than 20 turtles were rescued from the mud at this time and transferred to the San Francisco Zoo. |

© Mark Gary Heavy rain filled the pond to this level in late October 2021, but most of the turtles were already gone. The water level continued to increase during the winter rainy season. |

© Mark Gary This is the pond in early May, 2022. It's covered with algae, which makes counting turtles difficult, but about 60 turtles were seen. |

© Mark Gary The pond in early November, 2022 has dried up again with water only a couple of inches deep in most parts. No turtles were observed. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Luis Obispo County | Habitat, Afton Canyon, San Bernardino County. According to Stebbins (2003) the turtles in this desert population may be a distinct taxon. | Habitat with turtle, Los Angeles County © James R. Buskirk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Orange County © Jason Jones | Habitat, Panoche Valley, Fresno County © James R. Buskirk |

Habitat, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Luis Obispo County © Joel A. Germond |

Habitat, small creek, Santa Clara County | Habitat, Contra Costa County | Adult basking on branches in pond, Contra Costa County. Where no objects are available in the water for basking, pond turtles will use branches overhanging the water, or they will bask on the shore. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Mateo County | Habitat, Alameda County | Habitat, small lake, Santa Clara County © Cait Hutnik |

Habitat, Alameda County © Mark Gary |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Mateo County | Habitat, Contra Costa County | Habitat, 2,300 ft., Monterey County | San Mateo County Park Sign |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos of Southwestern Pond Turtles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southwestern Pond Turtles compete for limited basking space on a small pond. | Southwestern Pond Turtles basking in the sun. |

Southwestern Pond Turtles in an Alameda County pond. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | G2G3 | Imperiled-Vulnerable |

| NatureServe State Ranking | S2S3 | Imperiled-Vulnerable |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | FPT | Proposed for ESA listing as Threatened 20231003 |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | SSC | Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management | S | Sensitive |

| USDA Forest Service | S | Sensitive |

| IUCN | VU | Vulnerable |

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -