Lizard Behavior and Life History

| These are pictures and videos that illustrate some of the interesting behavior and or natural history of lizards from California and around the world. This is not an attempt to illustrate everything, only what is depicted elsewhere on this website. Follow the links on the name of each species to find more pictures and information about it. |

|||

| Miscellaneous Lizard Observations | |||

|

|

|

|

| This video shows several Northern Desert Iguanas in the Colorado Desert, including one emerging from it's hiding hole. | Southern Alligator Lizards are good climbers, using their somewhat prehensile tail to hold on, but they aren't easy to spot in trees since they blend in well with the branches. This adult with a very long intact tail frequents this Mulberry tree. © Sylvia Durando | Lizards hide in holes, cracks, and under rocks and other objects. These pictures show where a Variegated Skink hid itself under a rock. |

|

|

|

|

|

| In this short video, a leopard lizard slowly wriggles its long tail as if using it as a lure. Or maybe it's a nervous behavior. | Long-tailed Brush Lizards are very well camouflaged when they align their bodies on a branch and remain motionless inside a shrub, as you can see in the picture on the left and the video on the right. | This short video shows the desert habitat of a Common Chuckwalla, then zooms in on the cryptic lizard, in a typical pose for a Chuckwalla or any lizard, basking high on top of a rock. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fringed-toed lizards use fringed scales on their toes to help them run over loose sand. Shown here is the rear left foot of a Colorado Desert Fringe-toed Lizard. | Fringed-toed lizards also have fringed eyelids to help keep sand out of their eyes, as you can see on the closed eye of this Mojave Fringe-toed Lizard. | Sometimes it's easy to understand why a species was given its name. This one's name is Side-blotched Lizard, for obvious reasons - it has a dark blotch on it's sides. | On this Western Zebra-tailed Lizard you can see the Parietal Eye, or Third Eye, which is the small dark circle in the middle of the top of the head, slightly behind the eyes. Studies have shown that lizards use this patch of light-sensitive cells as a type of compass which lets them calculate their position and navigate by the sun. |

|

|

|

|

Australian geckos of the genus Nephrurus - Knob-tailed Geckos, including this Prickly Knob-tailed Gecko, have a small spherical knob at the end of the tail, the function of which is not known. The complete tail can be severed at its base by the gecko in order to distract a predator and when a new tail grows back it does not have a knob. Some theories* about the function of the knob are: it could be a sense organ that responds to some kind of sensory stimulation; it could be used for heat exchange in thermoregulation; it could be vibrated on the ground to make a buzzing sound that distracts predators; or it could be used in social encounters. * Eric R. Pianka, Laurie J. Vitt. Lizards: Windows to the Evolution of Diversity. UC Press, 2003. |

Horned lizards have nasal valves which they can close to keep soil from entering their nostrils and lungs when they bury themselves to hide or sleep. This Southern Desert Horned Lizard has closed its nasal valves. The closed valves leave a small crescent-shaped opening through which the lizard can still breathe when it is buried. © Filip Tkaczyk |

In this video, a Plateau Striped Whiptail, digging in a hole, stops and slowly waves its arms and tail in a strange behavior I can't explain. |

|

|

|

|

|

| In 2010, researchers at UC Santa Cruz discovered that Desert Night Lizards - Xantusia vigilis, live in family groups, showing social behavior more typical of mammals and birds such as primates, ground squirrels, and woodpeckers. The young night lizards remain with the father, mother, and siblings for several years, all living under the same plant debris.The young feed themselves and do not receive any direct care from the parents. It is not yet known what survival advantages the group living arrangement provides. (ScienceDaily 10/10) A few other lizard species have also evolved a social system around a nuclear family, including the Great Desert Skink of Australia, which lives in families consisting of a breeding pair and several generations of young. The families live in complex tunnel systems with up to 20 entrances and separate latrine areas that have been dug and maintained by the extended family. (Science Daily 5/11) |

Some lizards can excrete excess salts through their nostrils, like this Coast Range Fence Lizard. © Guntram Deichsel |

When the temperature of the surface is too high for a Texas Greater Earless Lizard's thin toes, it raises them up to keep them cool, resting on the balls of the feet which can handle the heat. Zebra-tailed lizards also do this as do other desert lizards where the temperature of a basking rock may be over 130 degrees F. (55 C.)! yet you will still see them basking on the rock with the toes of all four hands and feet raised up. | |

|

|

|

|

| Some lizards have transparent lower eyelids, like this Great Basin Whiptail. The eyelid is open on the left, and closed on the right. |

This La Palma Lizard (Gallotia galloti palmae) from La Palma Island in the Canary Islands, is "praying" - raising her hands and feet up off the hot wood to keep them from getting burnt. According to Guntram Deichsel "The blood vessels in her fingers and toes are so small that they cannot transport the heat taken up from the surface away sufficiently." The technical term for the position is "orate fratres", which translates as "Pray, brethren." © Guntram Deichsel 2008 | Starred Agama (Stellagama stellio) Sarigerme, Turkey © Guntram Deichsel 2015. This lizard has also assumed a "praying" or "orate fratres" position, protecting its sensitve fingers and toes from the hot surface, as seen with the La Palma Lizard to the left. |

|

|

|

|

|

| This Australian Hosmer's Skink has large spiny scales on its body that make it difficult for a predator to remove it from the cracks in large boulders where it takes shelter. |

Australian Yakka Skinks live in communal burrow complexes under rocks and logs and their presence is often detected by their communal defecation site. | ||

|

|

|

|

| Adult Southern Alligator Lizard, photographed lying still at the edge of a trail in San Luis Obispo County © Joanne Aasen Alligator lizards sometimes tuck their legs along the sides of their body when they move or when they remain still. Sometimes people think they are looking at a snake when they don't see the legs sticking out. This might be a defensive pose that makes the lizard look like a snake, to prevent a predator from approaching it, or it might be a tactic to make the lizard appear to be something that is not alive such as a stick. This could be effective against flying predators. |

This Southern Alligator Lizard was found with the rear half of its body stuck inside a discarded beer can in Santa Clara County. This might be proof that some lizards use beer cans as protective shells in the same way that hermit crabs use borrowed shells. Or more likely it just shows that the lizard entered the can looking for food or shelter (or maybe beer) and got stuck trying to get out. © Katie Quehl. | ||

|

|

|

|

| I always thought alligator lizards got their name from their body shape and large scales that are similar to alligators, but this sub-adult Southern Alligator Lizard in Nevada County dove into a stream and swam away just like its namesake. © Lou Silva | This juvenile Sand Lizard is spreading its ribs out to flatten its body, which enables it to absorb more of the sun's rays to warm up its body. © Guntram Deichsel |

||

|

|

|

|

| These two videos show a Northwestern Fence Lizard appearing to taunt a garter snake (a Mountain Gartersnake is my guess, because it lacks red.) The lizard keeps moving down towards the snake but when the snake moves towards the lizard, apparently trying to catch it for dinner, the lizard runs up the wall away from the snake. © Rod | This Bakersfield Legless Lizard somehow tied itself in a knot. It was loose enough that it was able to get out of it. Click on the thumbnail to see pictures of the lizard as it tied itself up. © Ryan Sikola |

This adult Great Basin Collared lizard was observed in Lassen County in early April when they were just coming above ground after brumating during winter. This lizard is covered with dried mud, so maybe uts sheltering location got wet. © Don Cain | |

| Lizard Defensive Strategies | |||

| Biting or threatening to bite, running away, hiding, staying still to hide by camouflage, dropping the tail as a distraction, squirting blood, burying in sand, jumping into water, exposing bright colors as a warning - these are some of the tactics lizards use to defend themselves when they feel threatened by a predator or in a territorial dispute with others of their own kind. Probably the most well-known defensive tactic used by lizards is dropping the tail to create a distraction, known as "tail autotomy" or self-loss. Follow the link to see a page illustrating this tactic. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| In these pictures we see a Southern Alligator Lizard, that dropped its tail after it was captured for a photo session. The tail wriggled on the ground as you can see in the video on the right. Typically, whatever was attacking the lizard would see the movement of the tail and go after it, distracting it from the lizard long enough for it to run away to safety. We felt terrible to be responsible for the loss of such a nice unbroken tail, but in time the tail will grow back, almost as good as the original. | ASouthern Alligator Lizard's tail, released from the body, thrashes around wildly on the ground in this video. This is the same tail shown to the left. | ||

|

|

|

|

| This injured Coast Horned Lizard shows blood above one eye. When threatened, horned lizards will often spurt blood from a pore near the eyelid to deter the attacker, in this case, a dog. © Martha Lindl | This Coast Horned Lizard squirted blood from its eyes just before the photographs were made, as you can see by the reddish coloring on its head. © Jackson Shedd |

The head of this Coast Horned Lizard is covered with blood after it used its blood-squirting defense behavior. © Curtis Croulet | |

|

|

|

|

| This juvenile Southern Desert Horned Lizard has recently used its blood-squirting defensive behavior. Horned lizard blood has been found to be very distasteful to some animals, especially Canines, causing them to drop the lizards without eating them. © Geoff Fangerow |

This video shows the excellent camouflage of a tiny Round-tailed Horned Lizard. Its color and shape allow it to blend in with the rocks on the ground. These lizards can also run away quickly when needed, as you can also see here. |

Every time I picked up a tiny Pygmy Short-Horned Lizard and set it down to try to film it in motion, it ran away quickly then stopped only a few feet away, where it remained still until I went to pick it up again, even though there were small bushes nearby that it could have run into to hide. The lizard was not relying on speed to escape, it was relying on its ability to blend in quickly with the background, expecting that I would not see it. This picture shows how well they blend in and disappear. |

This Texas Horned Lizard has elevated its body and filled itself with air to make it appear more threatening and too big to swallow. This is another defensive tactic used by horned lizards. |

|

|

|

|

| When I first picked up this Coast Horned Lizard it puffed up its body, raised up on its legs, and moved its head back and forth to let me feel the horns on its head. This is a typical horned lizard defensive behavior when they are captured, to which they sometimes add squirting blood from the eyes. | When threatened or annoyed, Gila Monsters, like this captive Banded Gila Monster, open their mouth and make a loud hissing sound. You can hear a recording of this Gila Monster hissing here. |

Fringe-toed lizards escape from danger by running quickly and rapidly burying themselves in the loose sand of the dunes they inhabit. This short video shows a Mojave Fringe-toed Lizard burying itself in the sand to hide. Unfortunately, this lizard was a captive and had gotten sluggish so it buries itself slowly and incompletely. In the wild, they do it so fast it looks like they suddenly disappear. | Flat-tailed Horned Lizards also quickly bury themselves in the loose sand of their habitat to escape from danger. In this short video you can see on run rapidly across fine wind-blown sand and then see it quickly bury itself with a final shake of its tail. |

|

|

|

|

| This Australian Frilled Lizard opens the thin skin around its neck into a brightly-colored warning to stay away. | This Australian Boyd's Forest Dragon clings to small trunks where it remains still to avoid detection. When encountered, it will slowly turn around the trunk to avoid showing its body, as this one is doing. This can be a little frustrating when you're trying to take a picture of it. | ||

|

|

|

|

| This Australian Eungella Broad-tailed Gecko has cryptic coloring and markings that match its habitat of large rainforest trees and a flattened body with a broad tail to help it remain camouflaged when it forages at night on the trees. | This Australian Wyberba Leaf-tailed Gecko has cryptic coloring and markings that match its habitat of large granite rocks and a flattened body with a broad tail to help it remain camouflaged when it forages at night on the rocks. | ||

|

|

|

|

| A Ventura County San Diego Alligator Lizard bites onto the nose of a predatory California Striped Racer, leaving the snake unable to strike. Eventually the lizard released its grip and the two ran in opposite directions. © Melissa Wantz |

Many lizards can swim when they need to. When this Skilton's Skink was discovered hiding under an object, it ran off, jumped into the water and quickly swam to get away. © Robert Mellinger |

Some lizards become bipedal when they run - they run on their back legs only to move more quickly as this Gilbert's Dragon is doing. |

In this short video we see a tiny juvenile Eastern Collard Lizard, disturbed from its sleep under a rock, defending itself by opening its mouth then jumping repeatedly at the camera. At one point it even bit and held on to the camera. |

|

|

|

|

| Disturbed from his hiding spot under a rock, an alligator lizard threatens to bite and hisses several times when he is touched, in this short video. | Alligator lizards have strong jaws which let them bite hard and hold on. | ||

|

|

|

|

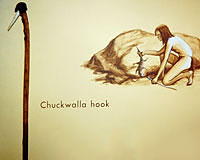

| Common Chuckwallas typically inhabit large rock outcrops. They often escape from danger by running into a crack in a rock, as this one did. They use both vertical or horizontal cracks, anything they can fit into. If you try to pull them out, they will inflate with air and that plus their rough skin makes it difficult to pull them out of a crack they have wedged into. Native Americans even made special hooks to help them pull Chuckwallas out of cracks. | This juvenile Common Chuckwalla was photographed after it emerged from a crack it used for shelter. © Mike Ryan | ||

|

|

|

|

| Jackson's Chameleons change their color to better blend in with their environment. This female changed her color from the picture on the left to the one on the right in about 20 minutes. | Green Anoles camouflage themselves by changing color from green to brown to match their environment. In this short video we see a male Green Anole quickly change his color from green to brown after he jumps onto a wooden post. |

||

|

|

|

|

| Nocturnal Granite Night Lizards have flattened bodies that allow them to hide from danger in thin cracks in large granite rocks, or under exfoliated flakes of granite on the surface of the rock. They also change color from a dark phase (seen here) to better help them hide in the crack, to a light phase when they are foraging on the rock surface at night, to help them blend in with the light granite that is flecked with dark spots. © Robert Black |

Light phase Granite Night Lizard on the surface of a rock at night. | Legless lizards live in loose substrate such as leaf litter or sandy soil. This video shows a Southern California Legless Lizard quickly burrow into loose soil. | This video shows a Bakersfield Legless Lizard burrow into loose soil. |

|

|

|

|

| Running away quickly up a tree or under a bush or into a hole, as this Northern Desert Iguana did, is one of the most common and effective ways a lizard can get out of danger. | This Australian Lace Monitor escaped capture by running way up a tree. | This Australian Southern Phasmid Gecko has evolved to climb up and camouflage itself on the stalks of the Spinifex plant it inhabits. | |

|

|

|

|

| Remaining motionless to avoid detection and to avoid triggering a predator's response to movement is another lizard defense strategy. After release from capture, this Coast Range Fence Lizard remained motionless in the position seen here for about a minute before turning over and running away. © Yuval Helfman |

When Marc Dyer took a ski lift up into the German Alps to go for a hike on March 30th, he expected to see a little snow left on the trail at about 1,800 meters (5,400 feet) but he certainly wasn't expecting to see a lizard walking on the snow. The lizard is called a Viviparous Lizard, Zootoca vivipara. It has the widest distribution of any species of terrestrial amphibian or reptile - ranging from Ireland all the way to Hokaido Island in Japan. It also lives farther north on the planet than any other species of non-marine reptile, up to 350 km (217 miles) north of the Arctic Circle in Scandinavia, making it one of the most cold-resistant lizards on the planet. Despite that, they are not typically seen on snow. This one was probably just traveling over the snow or maybe it was taking advantage of the reflective nature of the snow to soak up a little extra sun. Photo © Marc Dyer |

This video shows Western Zebra-tailed Lizards waving their striped tails to divert attention away from their body, running off quickly, and doing a territorial push-up display. | |

Skin Shedding |

|||

| LIzard skin does not grow as the lizard does, so when a lizard gets too big for its skin, it sheds the old skin in a process called ecdysis. This gives the lizard room to grow and helps to remove old or damaged skin. Unlike snakes, which typically shed in one piece, lizards shed in several pieces. | |||

|

|

|

|

| This adult male Eastern Fence Lizard in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, is shedding its skin. | This Plateau Striped Whiptail is shedding its skin. |

||

|

|

|

|

| Lizards shed their skin, usually a few times each year. Here, an adult male Desert Spiny Lizard in Arizona is shown with skin shed from its face and tail, but not yet from the rest of its body. | This Southwestern Fence Lizard is in serious need of a shedding. | Adult Great Basin Fence Lizard shedding its skin. © Ellen Goepfert | |

| Interspecific Social Interactions | |||

|

|

|

|

| This adult male Northwestern Fence Lizard and adult male Greater Brown Skink were photographed basking together in Placer County in late April © Rod |

This adult Skilton's Skink and Coast Range Fence Lizard were observed basking together frequently in a backyard garden in Marin County in April. This might represent a mate-guarding behavior by a male skink that confused the fence lizard for a female skink, or maybe they're just sharing a good basking spot, unconcerned about any threat from the other lizard. | ||

|

|

||

| This adult Moorish Gecko, a nocturnal species, is sometimes seen basking in the daytime in a yard in San Diego County. It often basks next to an adult Western Fence Lizard, but only briefly - not as long as the fence lizards bask. Juvenile fence lizards appear to avoid basking near the larger gecko. © John Nalevanko |

© John Nalevanko Six years after the picture to the left was taken, we can see what might be the same Moorish Gecko where it is seen almost every day basking beside one or two adult Western Fence Lizards. |

||

| Lizard Tongues | |||

|

|

|

|

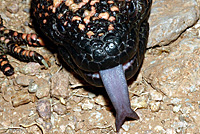

| A Reticulate Gila Monster flicks its wide forked tongue to sense its surroundings. | Burton's Legless Lizard | Geckos that have no eyelids use their tongue to clean their eyes. This Australian gecko is a Western Beaked Gecko | This Australian gecko, a Southern Phasmid Gecko, has no eyelids, so it cleans it's eyes with its tongue. |

|

|

|

|

| This large Australian skink, a Common Blue-tongued Skink, shows its blue tongue as a warning when it feels threatened. | Pink-tongued Skink | Spencer's Monitor | Black-headed Monitor |

|

|

|

|

| Perentie | Texas Spotted Whiptail |

Reticulate Gila Monster |

Eastern Collared Lizard |

|

|

||

| Note the slightly forked tongue on this Northern Alligator Lizard | A Mediterranean Gecko shows its tongue when it licks its lips. |

||

| Toes Specially Adapted For Climbing | |||

Some geckos have specialized toe pads to help them climb up slick vertical surfaces, and even upside down on ceilings. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| Common House Gecko on the outside of a glass window at night | Mediterranean Gecko | ||

|

|

|

|

| This picture shows the amazing climbing abilities of a Mediterranean Gecko, as it climbs up a glass window. | Peninsular Leaf-toed Gecko | This Australian Southern Phasmid Gecko has toes that are adapted to wrap around and climb on the thin stalks of spinifex grass that it lives on. | |

| Changing Color | |||

|

|

|

|

| These two pictures show the same male Green Anole. Less than a minute after the picture on the left was taken (after he finished displaying his colorful throat dewlap, he changed his body color from green to brown. This is why some people call these lizards Chameleons. | Green Anoles camouflage themselves by changing color from green to brown to match their environment. In this short video we see a male Green Anole quickly change his color from green to brown after he jumps onto a wooden post. |

The bright pink color on a juvenile Western Red-tailed Skink (above) fades when it becomes an adult (below). | |

|

|

|

|

| These pictures all show the same feral female Jackson's Chameleon over a period of about 20 minutes after capture. Chameleons such as Jackson's change their color to match their surroundings. |

Adult Western Red-tailed Skink without the pink tail of a juvenile (above). | ||

|

|

|

|

| Many lizards change their color depending on their temperature. Some can match the color of their surroundings. These pictures show the same Mediterranean House Gecko, first in its dark phase when it was discovered under a rock in an ice storm, and second, after it had warmed up inside the house. |

Many kinds of juvenile skinks have a bright blue tail that fades with age. These are a juvenile (left) and an adult (right) Skilton's Skinks. |

||

|

|

||

| In the daytime, when they hide in the shade, Granite Night Lizards are in their dark phase (left) but when they come out at night to hunt on large boulders they are in their light phase (right). | |||

| Changing Color During the Breeding Season | |||

|

|

|

|

| This male Five-lined Skink in Kansas has developed bright red coloring during the breeding season (left). A non-breeding Five-lined Skink from Maryland is shown on the right for comparison. | This adult male Northern Brown Skink has developed red coloring on the head and tail during the breeding season. | During the breeding season, male Fence Lizards develop a more intense blue coloration to show off to females and to rival males, as you can see in this confrontation between two adult male lizards. © Kathleen Scavone | |

|

|

|

|

| Female Long-nosed Leopard Lizards develop red spots when they are full of eggs in the breeding season. | Female Great Basin Collared Lizards also develop red coloring during the breeding season. | Female Mearn's Rock Lizards develop red and blue breeding colors. © Stuart Young | |

|

|

|

|

| This gravid female Western Sagebrush Lizard shows her bright red breeding colors. | This adult male Skilton's Skink is showing his red breeding colors (left & middle). © Alan Barron A non-breeding colored adult is shown on the far right. |

||

| Changing Color with Age | |||

| These are not pictures of three different lizards but they illustrate how the color changes in the Peninsular Banded Gecko. Hatchlings have a brightly colored body with a bright black and white tail (1) but as they grow the body turns brown and the tail starts to fade (2) until it attains its adult coloration (3 and 4). | |||

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile © Jason Jones | Juveile © Kevin Law | Adult from San Diego County | Adult from Baja California © Stuart Young |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile Green Iguanas (left) start out bright green, but become dull green or grey when they become adults (middle and right.) | |||

| External Parasites on Lizards | |||

| Ticks | |||

|

|

|

|

| It is common to find blood-engorged ticks attached to alligator lizards, especially in and around the ear openings, as you can see on the California Alligator Lizard on the left, on the Shasta Alligator Lizard in the middle, and on the San Francisco Alligator Lizard on the right. |

Adult California Alligator Lizard infested with ticks behind the ear. © Julia Ggem | ||

|

|

|

|

| This adult male Western Fence Lizard has several ticks on the side of his head and in his ear. In California, western black-legged ticks (deer ticks) are the primary carriers of Lyme disease. Very tiny nymphal deer ticks are more likely to carry the disease than adults. A protein in the blood of Western Fence Lizards kills the bacterium in these nymphal ticks when they attach themselves to a lizard and ingest the lizard's blood. This could explain why Lyme disease is less common in California than it is in some areas such as the Northeastern states, where it is epidemic. More Information |

Adult Coast Range Fence Lizard, San Luis Obispo County, with several ticks in its ear. © Ryan Sikola |

Adult male Short-lined Skink, parasitized by a tick behind the right foreleg. |

|

| Mites | |||

| Some lizards are infested with ectoparasitic red mites called chiggers, which are the six-legged larvae of trombiculid mites. Chiggers pierce the skin and inject saliva which causes an inflamed reaction leading to cell breakdown and an increase in tissue fluid. (If you have ever had chiggers on your body, you know how uncomfortable and long-lasting a chigger bite bite can be, and usually you will have dozens of chiggers!) After feeding on the lizard, the chiggers increase in size then drop to the ground where they metamorphose into the adult form of the mite. Instead of making themselves inhospitable to the parasites, some lizards have specialized mite pockets that provide a warm and humid site where chiggers can live and feed easier. (Occasionally ticks are also found in the mite pockets.) Mite pockets are typically found on the side of the neck, in the armpit region, the groin area, high on the side of the chest, and at the side of the base of the tail, but most species have pockets in only one place, occasionally two. (I don't know if the pictures below show mites in mite pockets or in random collections.) It remains unclear why some lizards provide mite pockets and how they benefit from an association with the parasites. Mite pockets are found on newly-hatched lizards, so they do not form in reaction to mites - the pockets have evolved with the lizards. There does not appear to be any significant impairment of adult lizard growth due to the parasites. One explanation is that the mite pockets help to concentrate the mites to specific areas avoiding an infestation of mites over the body that could overwhelm the host. It is also thought that the pockets actually reduce mite feeding efficiency and limit mite damage to the lizard's superficial tissues which reduce irritation of the lizard. There is some excellent information about mites and captive lizards on Anapsid.org * Michael J. Benton. The Mite Pockets of Lizards. NATURE Vol. 325, pp. 391-392 29 January 1987 * Jay Clark Reed. Analysis of the Function and Evolution of Mite Pockets in Lizards. University of Michigan Dissertation, 2014. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| A Desert Iguana with mites on the neck and elsewhere. |

A Long-nosed Leopard Lizard with mites on the neck. |

Western Sagebrush Lizard with mites scattered around the neck |

This Moorish Gecko has red mites on its body and between its toes. © Laura A. |

|

|

|

|

| Wild collard lizards sometimes have clusters of red mites under folds of skin around their neck or legs. These mites are a non life-threatening nuisance in the wild, but they can increase in numbers enough to kill a lizard in captivity if they are not removed. | This Five-lined Skink has red mites on its toes. |

A Desert Iguana with mites behind its rear leg. |

|

|

|||

| This Western Side-blotched Lizard has mites on the neck, behind the back legs, and on the tail. | |||

| Scale Types Found on California Lizards | |||

|

|

|

|

| The Collared Lizards, genus Crotaphytus, have granular scales on the back. |

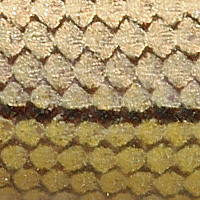

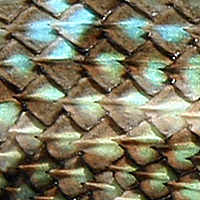

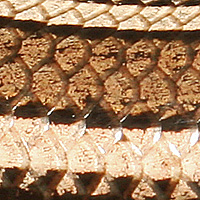

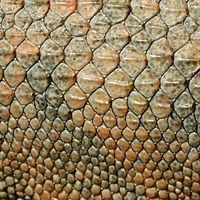

The Western Alligator Lizards, genus Elgaria, have large rectangular keeled scales on the back that are reinforced with bone. | The North American Legless Lizards, genus Anniella, have smooth cycloid scales. | The Side-blotched Lizards, genus Uta, have small keeled spineless scales on the back. |

|

|

|

|

| Desert Spiny Lizard | Western Fence Lizard | Sagebrush Lizard | Granite Spiny Lizard |

| The Spiny Lizards, genus Sceloporus, have overlapping scales with sharp spines on the back. |

|||

|

|

|

|

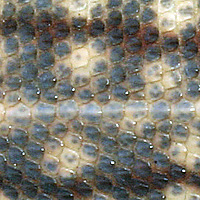

| The Chuckwalla, Sauromalis ater, has a back covered with granular scales. | The Toothy Skinks, genus Plestiodon, have smooth shiny cycloid scales that are reinforced with bone. | The Zebra-tailed Lizard, genus Callisaurus, has smooth granular scales above. | The Gila Monster, genus Heloderma, has round scales on the back that look like beads. |

|

|

|

|

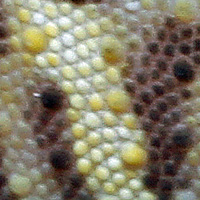

| The Banded Geckos, genus Coleonyx, have fine granular scales on their soft skin. | The Peninsular Banded Gecko, Coleonyx switaki, has soft skin with small granular scales interspersed with larger tubercles. | Leaf-toed Geckos, genus Phyllodactylus, have small granular dorsal scales that are interspersed with enlarged keeled tubercles. | The Desert Iguana, Dipsosaurus dorsalis has small granular scales on the back with a row of slightly larger keeled scales on the middle of the back. |

|

|

|

|

| Tree Lizard | Long-tailed Brush Lizard | Small-scaled Lizard | The Leopard Lizards, genus Gambelia, have granular scales on the body. |

| The Tree and Brush Lizards, genus Urosaurus, have a mixture of small granular scales and larger weekly-keeled scales on the dorsal surface. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| The Night Lizards, genus Xantusia, have small granular scales on soft skin. | The Fringe-toed Lizards, genus Uma, have soft and smooth skin with granular scales. |

The Whiptails, genus Aspidoscelis, have small granular dorsal scales. | |

|

|

|

|

| Flat-tailed Horned Lizard |

Coast Horned Lizard | Desert Horned Lizard | Pigmy Short-horned Lizard |

| The Horned lizards, genus Phrynosoma, are covered with small granular scales interspersed with larger pointed scales on the dorsal surfaces. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| The California Rock Lizard, Petrosaurus mearnsi, has small granular scales on the dorsal surfaces, and pointed keeled scales on the tails and limbs. |

The Green Anole, Anolis carolinensis, has small granular scales. |

The Brown Anole, Anolis sagrei, has small granular scales. | The Mediterranean House Gecko, Hemidactylus turcicus, has soft skin with prominent knob-like tubercles. |

|

|

||

| The Italian Wall Lizard, Podarcis siculus, has small granular scales on the back. | Moorish Wall Geckos have small granular scales with intermittent large tubercles. |

||

| A California Lizard Travels to Germany | |||

|

|

||

| The lizard shown directly above was found in a freight container containing only metal boxes at the BMW plant in Dingolfing / Bavaria / Germany on Oct 17, 2006. The container was shipped from Stockton CA on Sep 14, 2006. The lizard survived a 33 day voyage without food and water. The container was placed most likely on the top deck of the vessel and hence cooled down considerably at night which explains the good condition of the animal upon arrival. Photos © Jochen Späth Information: Guntram Deichsel Many species of plants and animals have been introduced into areas of the planet where they did not naturally evolve. The journey of this lizard illustrates one way animals can spread around the globe: If the lizard was a gravid female who found conditions favorable to her survival once she arrived, laid her eggs, and eventually the offspring began reproducing, or if other lizards arrived at the same location and bred with her, then an established breeding population could develop. |

|||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -