Long-toed Salamander - Ambystoma macrodactylum

Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander -

Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum

Russell and Anderson, 1956

Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

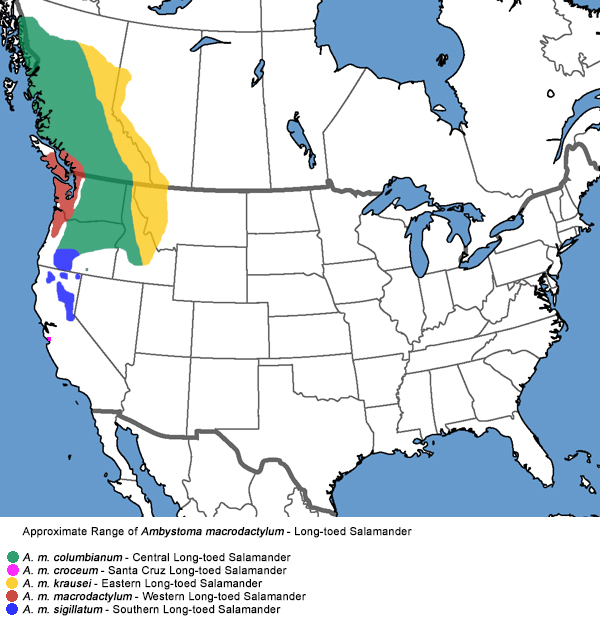

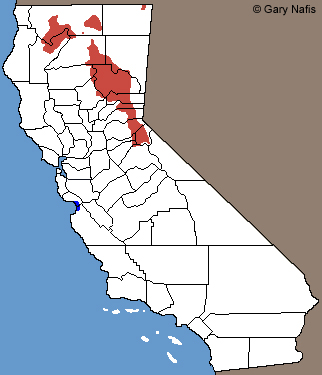

Bright Green: Range of this subspecies in California

Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum -

Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander

Range of other subspecies in California:

Red: Ambystoma macrodactylum sigillatum -

Southern Long-toed Salamander

Click on the top map for a topographical view.

Click on the bottom map for a larger view.

Map with California County Names

Dark Blue: Range of this subspecies

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Spencer Riffle |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Zach Lim | Adult, Santa Cruz County © Brad Alexander |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County |

Adult, Monterey County © Zach Lim | Adult, Monterey County © Zach Lim | Adult, Monterey County © Zach Lim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County © Spencer Riffle |

Adult, Monterey County © Dave Feliz | Adult, Santa Cruz County © Spencer Riffle |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Spencer Riffle |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This dark and nearly unmarked adult was found in Santa Cruz County. © James Maughn |

This Santa Cruz County salamander was found climbing some grass at night, apparently hunting for food, probably small slugs. © Jared Heald | This Santa Cruz County salamander is displaying a defensive posture after being disturbed by bright light at night. © Jared Heald |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adults found on a rainy night in Santa Cruz County © Adam Gitmed | This Santa Cruz County salamander was discovered eating an earthworm. © Jared Heald |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Santa Cruz County, handled with proper federal and state permits. © Leyna Stemle |

Adult female, Santa Cruz County, handled with proper federal and state permits. © Leyna Stemle |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Benjamin Genter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Looking at the salamander on the left and the willow leaf on the right you can see how the pattern on the salamander helps it blend into its environment to remain undetected. © Ryan Sikola | Recently-metamorphosed juvenile, Santa Cruz County, with native willow leaves they blend in with that are common in the breeding area, handled with proper federal and state permits. © Leyna Stemle |

An elongated toe (number 4) on each hind foot is the "long toe" that gives this species its common name. | © Spencer Riffle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of two sympatric Ambystomatid salamanders: Left: Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander Right: California Tiger Salamander, handled with proper federal and state permits. © Leyna Stemle |

Adult, dorsal pattern close-up, Santa Cruz County © Ryan Sikola | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transformed Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two recently-metamorphosed juveniles, Monterey County © Dave Feliz | Recently-metamorphosed juvenile, Monterey County © Dave Feliz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metamorph, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle |

Metamorph, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle |

Metamorph, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle |

Metamorph, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile © Jon Hirt | Juvenile, Santa Cruz County © Jon Hirt |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Larvae | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Larva in water, Monterey County © Dave Feliz | Larva in water, Monterey County © Dave Feliz |

Larva, Santa Cruz County © Aidan O'Brien |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aquatic Larvae, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle | Aquatic Larvae, Santa Cruz County The second larva from the left has almost completed metamorphosis, having reabsorbed most of its gills and excess dorsal tail. The others show no signs of metamorphosis yet. © Leyna Stemle |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aquatic Larva, USFWS | Aquatic Larva, USFWS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sympatric Salamander Larvae | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Taricha granulosa There are large dark areas on either side of the light coloring around the pupil |

Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum There are no large dark areas in the light coloring around the pupil |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ambystoma californiense Snout is broader, more shovel-shaped Color is mostly gray, or with a little green or blue Toe is more wedge-shaped |

Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum Snout is more rounded Color ranges from black to mottled green and tan to gray Toe is a little more skinny and long |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| More Pictures of Eggs, Larvae, and Young of Other Subspecies of Long-toed Salamanders |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dry breeding pond in November, Santa Cruz County |

Breeding pond, winter, Santa Cruz County |

Breeding pond, late winter Santa Cruz County |

Wildlife refuge habitat (name removed) Santa Cruz County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dried wetland breeding habitat in August, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle | Upland habitat, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle |

Breeding pond habitat, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle | Upland habitat, Monterey County © Leyna Stemle |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding pond in late summer, Santa Cruz County © Leyna Stemle | Habitat, Monterey County © Dave Feliz |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | G5 T1 T2 |

Species Secure. Subspecies Critically Imperiled - Imperiled |

| NatureServe State Ranking | S2 | Imperiled |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | FE | Listed as Endangered 3/11/67 |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | SE | Listed as Endangered 6/27/71 |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | FP | Fully Protected |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -