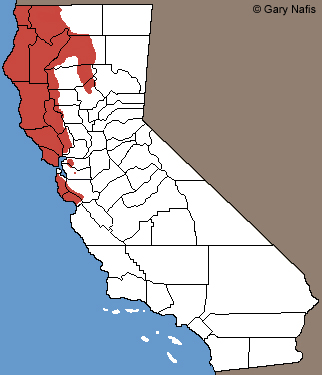

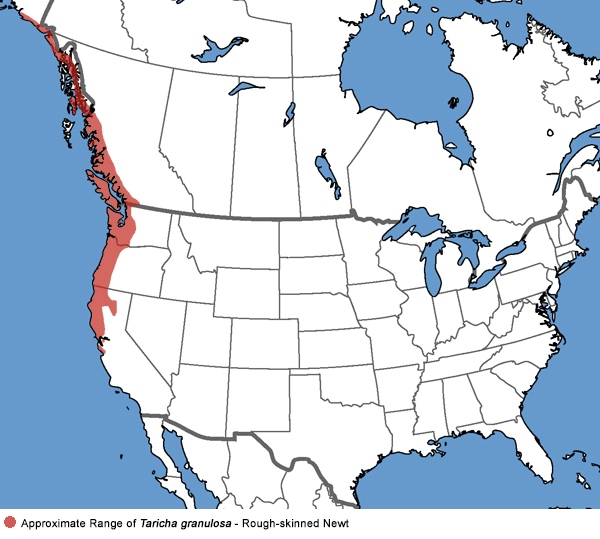

Rough-skinned Newt - Taricha granulosa

(Skilton, 1849)Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Butte County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Humboldt County | Breeding adult female, Butte County | Adult, Mendocino County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding adult female, Butte County | Breeding adult male (on bottom) with breeding adult male Sierra Newt (on top) Both were found in the same pool of water in Butte County. | Breeding adult male, Butte County | Adult, Mendocino County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding adult male, Butte County | Adult male, Butte County | Adult, Butte County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Butte County | Adult, Tehama County © Jackson Shedd | Adult, Marin County © Andre Giraldi | Adult male in water, Sonoma County © Lou Silva |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult in aquatic phase, Del Norte County © Alan Barron | Adult in aquatic phase, Del Norte County © Alan Barron | Adult in terrestrial phase, Del Norte County © Alan Barron | Adult, Sonoma County © Lou Silva |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High-contrast male, Marin County © Adam Gitmed |

Adults swimming in a pond in Summer where they live all year, Thurston County, Washington |

Adult, Napa County © Teejay O'Rear | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very dark aquatic phase adult, photographed in a lake at about 7,000 ft. elevation (2133 m) in Siskiyou County in July. © Rowan Moore Gerety | Adult, Santa Cruz County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rough-skinned Newt Skeleton National Museum of Natural History |

© Regan Sikola Top: Rough-skinned Newt Bottom: California Newt This is a good illustration of how the eyes don't extend past the margin of the head on T. granulosa but they do on T. torosa. |

When seen from above, the eyes of a Rough-skinned Newt, T. granulosa, do not extend to or beyond the margin of the head. Compare with T. torosa, the California Newt, on the right and with other newts found in California here: Newt Identification. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult Defensive Posture | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, defensive posture, Del Norte County |

Adult, Lewis County, Washington This newt is in a defensive posture called "unkenreflex"in which it displays its brightly-colored underside as a warning. The Rough-skinned newt curls it's colorful tail. Compare with the straight tail of the sometimes sympatric California Newt and the sometimes sympatric Sierra Newt. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult in defensive posture, Douglas County Oregon. (Note that this newt is not curling its tail over the back, which is the typical behavior for this species.) |

Breeding adult male in defensive posture, Butte County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Juveniles |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Del Norte County | Juvenile, Santa Clara County | Recently metamorphed juvenile | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This incredible collection of hundreds or perhaps thousands of juvenile newts was found in Napa County in late September under a boat near a lake that had a small amount of water remaining in it during a year of severe drought. No newts were found at the same location four days previously. Two species of newts are found at the location, California Newts, and Rough-skinned Newts. Some of them appear to be California Newts, but it's not possible to know the species of all of them. Recently-transformed newts sometimes gather into masses in order to help them retain moisture which can be lost through the skin. © Anonymous |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

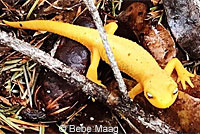

| Unusual Color Variations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This apparently leucistic juvenile Rough-skinned Newt was found in Santa Cruz County © Bebe Maag | Adult with an unusually pale venter that could be due to an autoimmune issue. Humboldt County © Spencer Riffle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This unusual Rough-skinned Newt with a light ground color and dark blotches, was found near the coast in Tillamook County, Oregon in an area with many other typically-colored newts. Populations of unusually-colored or blotched newts have been found in several places on the West Coast which I have listed below in the description of this species. This newt might be part of a similar population or it might be just a single individual with a pigment aberration. © Matt D'Agrosa and Yvonne Stotler |

This is a short video of the newt described to the left. © Matt D'Agrosa and Yvonne Stotler |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This unusually-colored Rough-skinned Newt, photographed in a shallow creek on the northern Sonoma County coast, has gray skin, black bumps on its back (its "rough skin"), and there is a little bit of the natural color remaining on some of its toes and behind at least one of its legs. (What looks like a split in the tail, is probably the top of the dorsal fin seen from directly above.) © Dorothy Yerxa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding and Predation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Several breeding adult newts in a breeding pond eating amphibian eggs, possibly Northwestern Salamander eggs. Many Northern Red-legged Frog eggs were also seen at the location. |

Santa Cruz Gartersnake eating a young newt © Odophile.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The eight pictures above show several Rough-skinned Newts eating earthworms on a road at night in Marion County, Oregon. They were among more than a thousand adult female newts that had migrated out onto the road on two rainy nights in late January & early February to take advantage of the worms which had crawled onto the road. The females were feeding before heading to the breeding pond, which was already full of males awaiting their arrival. © Chris Rombough | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This adult newt (shown in water) is being attacked by a predatory diving beetle. © Lou Silva | This short video shows several Rough-skinned newts in Pacific County, Washington, interact with an underwater egg mass that could be from A. gracile - Northwestern Salamander, or possibly a Long-toed Salamander. Some of the newts appear to be trying to bite the eggs as if to eat them, while others seem to just thrash around without taking any bites. | This short video shows several Rough-skinned newts in a Tillamook Co., Oregon coastal lake, 3.5 feet offshore and in 12" deep water feeding on largemouth bass eggs, most less than 1 mm in diameter. Male largemouth bass construct a nest where the female lays her eggs. It is often a circular depression in the substrate or a patch of submerged vegetation. In this case the nest is the patch of moss in which we see the newts, and the eggs are sticking to the strands. © Chris Rombough |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mating Activity, Eggs and Larvae | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding adult male (top) and breeding adult female (bottom), Butte County | Male and female in amplexus in water, Pacific County, Washington | Male and female in amplexus in water, Pacific County, Washington | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mating ball, Southwest Oregon, © Steven Krause |

Egg on submerged blade of grass, Thurston County, Washington. © 2004 William Leonard |

Larva (in water) Sonoma County © Lou Silva |

Gilled juvenile found on land and photographed in water. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Larvae (in water) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Larvae (in water) | Larva (in air) Santa Cruz County © Aidan O'Brien |

During the breeding season, adult males develop nuptial pads on the toes to improve their ability to hold onto females during amplexus. Compare with the toes of a breeding female without these pads. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metamorphs, found on land at the edge of a pond, and photographed in water. Notice the trace of gills remaining | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rough-skinned Newt Habitat in California | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Mendocino County | Habitat, San Mateo County |

Habitat, near sea level, Del Norte County | Habitat, San Mateo County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Siskiyou County |

Habitat, 5,700 ft. Siskiyou County | Habitat, Humboldt County | Breeding pool in coniferous forest, Butte County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rough-skinned newts move around the rocky shallow margins of a river in Douglas County, Oregon, occasionally coming up for air. |

A few light taps on the back of a Rough-skinned Newt causes it to take a passive defensive posture, raising its tail and head to display the bright orange color of its underside which signifies danger. This "unken reflex" shows a would-be predator that the newt is deadly poisonous, while at the same time, the newt releases deadly toxins from its skin. | Pairs of Rough-skinned newts in amplexus in a breeding pond. | A male and a female Rough-skinned newt in their underwater amplexus ballet. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male newts in the breeding pond wrestling over and waiting for females. | Solo male newts and males and females in amplexus swim underwater in a breeding pond in Pacific County, Washington in mid February. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. This salamander is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | Not Known | |

| NatureServe State Ranking | Not Known | |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | Not Known | |

Return to the Top

© 2000 -