|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Bernardino County |

Sub-adult, San Bernardino County |

Sub-adult, San Bernardino County |

Adult, Riverside County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult from Afton Canyon, San Bernardino County |

Adult, Stanislaus County |

|

|

|

|

These three adult toads were photographed at night as they sat on the vegetation

of a small pond in Los Angeles county, apparently hunting in ambush mode. |

Adult, Borrego Valley, San Diego County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Riverside County |

Adult, San Diego County |

Sub-adult, Stanislaus County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County, as it was found hiding under a fallen log in February. |

Adult, Riverside County |

An adult with an irregular dorsal stripe in a breeding creek in Santa Clara County. |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Santa Barbara County © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile California Toads found in southern California are sometimes mistaken for Red-spotted Toads when they have lots of red spots on their backs, like this one from Contra Costa County. |

Adult, Marin County © Andre Giraldi |

Adult, Lassen County © Debbie Frost |

Juvenile, Lassen County © Debbie Frost |

|

|

|

|

Adult emerging from a California ground squirrel burrow (lower left of photo on right)

Contra Costa County. |

Adult, Darwin Falls, Inyo County |

|

|

|

|

Toads are surprisingly good climbers. This California Toad was photographed climbing the steep walls of a canyon

in San Bernardino County to get to a burrow, which you can see in the third picture. © Jeff Ahrens

|

Adults, Orange County

© Ivan Vershynin & Noah Shipman |

|

|

|

|

| This venerable old California Toad was found as a tadpole in Orange County in 1993 and raised in a grade school classroom. It's 21 years old in these photographs taken 9/14. |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Zach Lim |

|

|

|

|

| Adult toad at the edge of a breeding pond in Contra Costa County during the breeding season, probably a male waiting for a female. © Mark Gary |

Adult male in Contra Costa County breeding pond |

Adult, Santa Clara County

© Yuval helfman |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Marin County © Ben DeDominic |

Adult, Santa Clara County © Zach Lim |

This Sonoma County toad shows white milky secretions from the parotoid glands which contain noxious chemicals that help to deter some predators.

© Dominic Poole |

Close-up showing large oval parotoid

glands behind the eyes. |

|

|

|

|

Adult from intergrade zone with

B. b. boreas, Shasta County |

Tracks made by a California Toad in

San Diego County © Gina Krantz

(Merkel & Associates, Inc.) |

Toads usually move, as this one is doing, by walking or crawling, along with some short hops, while true frogs typically move mostly by hopping. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

Recently metamorphosed toadlet,

Contra Costa County. |

Recently metamorphosed toadlet,

Riverside County. |

Sub-adult, Riverside County |

Recently metamorphosed toadlets, Contra Cost County |

|

|

|

|

| These recently metamorphosed toadlets were found at about 9500 ft. elevation (2,900 m.) in the Sierra Nevada mountains on the Pacific Crest Trail near Mt. Whitney in Inyo County. At this elevation one might expect to see Anaxarus canorus - Yosemite Toad, but that species does not occur so far south. © Douglas S. Brown |

Sub-adult, Stanislaus County, showing brightly-colored pads

on the bottom of the feet that are found on young toads.

|

|

|

|

|

Juveniles, Ventura County

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Unusual Colors and Patterns & Hybrids |

|

|

|

|

Patternless adult, Alameda County.

© Nick Esquivel |

Very pale adult from a San Diego County Desert valley - looking similar to a

Red-spotted Toad. © Steve Bledsoe |

This tiny juvenile toad was found at Darwin Falls, Inyo County, where hypbrids with Red-spotted Toads - Bufo punctatus have been found. While it resembles a California Toad, it appears to be a hybrid since it lacks a dorsal stripe and has less oval and more rounded parotoid glands, similar to the Red-spotted Toad. © Ceal Klingler |

|

|

|

|

This adult found in a desert canyon in San Diego County, is missing some of its normal pigmentation, but it's not an albino because the eyes are dark.

© Cameron Ruland |

Adult male and female in amplexus in a San Diego County desert riparian area. The male appears to be leucistic. © Taylour Unzicker |

| |

|

|

|

| Predators |

|

|

|

|

Most toads are poisonous to other animals, or they taste so bad that a predator will not eat them. But this Valley Gartersnake had no concerns about eating a California Toad.

© Pamela Greer |

Toads are conspicuous and at risk during the breeding season when they enter the water and their movement attracts predators. Here we see the remnants of a male, seen next to some freshly-laid eggs, which was picked off and eaten by a predator during the breeding season in a Contra Costa pond. |

An adult Two-striped Gartersnake was observed eating a California Toad in San Diego County. It took the snake almost 45 minutes to completely swallow the toad, which had puffed its body up to make itself harder to swallow. You can also watch a YouTube video of the event:

Two Striped Garter Feeds on a California Toad © Douglas S. Brown |

This adult California Toad was apparently killed and its less-toxic internal organs eaten by a Shrike, a large songbird that is also sometimes called a "butcher bird" because of its habit of impaling the carcasses of its prey on a thorn, a cactus spine or a barbed wire fence, so it can return later to feed on the leftovers. This one was photographed in Contra Costa County

© Mark Gary |

|

|

|

|

The skin of this adult toad is all that was found in a Contra Costa pond. Whatever ate the toad (maybe a racoon) ate the insides and avoided the poisonous skin.

© Mark Gary

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Breeding Season |

|

|

|

|

| Adults in amplexus, San Joaquin County |

Adults in amplexus with eggs,

Contra Costa County. |

A large communal mass of egg strings,

Contra Costa County |

Single string of eggs,

Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Tadpole in water, Contra Costa County |

Mature tadpole with four legs in water,

Contra Costa County |

Recently metamorphosed toadlet,

Contra Costa County. |

Recently metamorphosed toadlet,

Riverside County. |

Go here to see lots more pictures of Breeding, Eggs, Tadpoles and Young

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Alameda County pond |

Habitat, snow-melt meadow pond at 9500 ft. elevation (2,900 m.) in the Sierra Nevada mountains in Inyo County.

© Douglas S. Brown |

Habitat, Contra Costa County pond

|

Habitat, Alameda County creek |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Contra Costa County pond

|

Breeding Habitat,

San Joaquin County creek |

Breeding pond, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, cattle pond in oak grassland, 1,900 ft., Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, desert river wetlands, Afton Canyon, San Bernardino County |

Habitat, desert spring, Darwin Falls,

Inyo County |

Habitat, pond in Sierra Nevada Mountains, 4,500 ft., Kern County |

Habitat, Los Angeles County pond |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, seasonal pool in Central Valley Grasslands, Merced County |

Habitat, small creek in Coast Range foothills, 500 ft., Stanislaus County |

Habitat, San Bernardino County creek |

Breeding habitat,

Santa Clara County creek |

|

|

|

|

Desert riparian creek habitat,

San Diego County |

Habitat, San Bernardino County creek |

Habitat, wetlands at 2,000 ft., Santa Rosa Plateau, Riverside County |

Breeding habitat,

Riverside County pond |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Alameda County pond

|

Seasonal pond used for breeding,

Contra Costa County.

Follow this link to see more pictures of this pond as it looked in different months

(of different years) showing how the pond and its surroundings change over the seasons. |

Breeding pond, Contra Costa County |

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| In late winter just before the breeding season, a huge California toad is found resting underneath a piece of wood near a pond. |

A male California Toad calls during daylight from the edge of a rocky creek in Alameda County (shown here). The call does not seem to be an aggressive or release call, because no other solo male toads were nearby or in contact with him, but there was an amplexing pair swimming back and forth in the water about ten feet away from him. |

A California Toad moves across the wet ground both by crawling and by hopping |

This short video shows the life cycle of the California Toad, from the late winter breeding season when frenzied males call and compete and pair up with females who lay long strings of eggs, to tiny black tadpoles just emerged from the eggs then developing and forming huge feeding masses, to the tiny toads, recently-transformed from tadpoles, massing together around the pond edge then dispersing on their own, to an adult toad moving about on its own, as it will remain until the next breeding season. |

|

|

|

|

| These videos show breeding behavior at the shallow outlet of a pond in Contra Costa County where at least 8 solo males and 10 pairs in amplexus were observed in the area. |

A male toad picked up out of the breeding pond makes the release call, then swims away. |

More videos are available here and here.

|

Herpetologist Sam Sweet has posted some outstanding descriptions of the biology of Arroyo Toads - Anaxyrus (Bufo) californicus - their breeding, egg deposition, tadpoles and metamorphs, illustrated with many excellent photographs, and including comparisons with sympatric California Toads. These are on public herping forums where you can see them here and here.

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults grow to 2 - 5 inches from snout to vent ( 5.1 - 12.7 cm). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A large and robust toad with dry, warty skin.

No cranial crests are present.

Parotoid Glands are oval and well-developed.

Pupils are horizontal.

|

| Color and Pattern |

The ground color is Greenish, tan, reddish brown, dusky gray, or yellow.

Rusty-colored warts are set on dark blotches.

There is much dark blotching above and below, becoming all dark at times.

The throat is pale on both males and females.

A light stripe is usually present on the middle of the back. |

| Male/Female Differences |

Males are usually less blotched than females and have smoother skin.

Females are larger than males and more stout.

During the breeding season, males have

dark nuptial pads on the thumbs and the inner two digits of the hands. |

| Young |

Young have no dorsal stripe immediately after transformation.

The bottoms of their feet is bright orange or yellow.

|

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are dark brown with eyes inset from the edges of the head.

The tip of the tail is rounded.

They grow to about 2.25 inches (5.6 cm) in length before undergoing metamorphosis.

|

| Comparison with Anaxyrus boreas boreas - Boreal Toad |

A. b. boreas:

"Considerable dark blotching both above and below. Sometimes almost all dark above..."

A. b. halophilus

"Generally less dark blotching than in Boreal Toad. Head wider, eyes larger (less distance between upper eyelids), and feet smaller."

(Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Comparison with Sympatric Anaxyrus californicus - Arroyo Toad |

| Adults |

Arroyo toads typically have a light stripe or V across the head and eyelids which is lacking on California Toads.

Mature California Toads typically have a pale dorsolateral stripe (a pale light stripe down the middle of the back) which is lacking on Arroyo Toads. |

| Juveniles |

Juvenile Arroyo Toads show the pale V between the eyes, pale spots on the sacral humps, yellow tubercles, and are unmarked ventrally.

Juvenile California Toads have no pale V or pale sacral hump spots, rust-colored tubercles, a pale dorsolateral stripe, and are marked with dark spots ventrally.

Juvenile Arroyo toads are typically found fully exposed in direct sunlight on the sandy banks

of the natal creek.

Juvenile California toads are typically found dug into wet sand at the edge of the creek, or in shade under vegetation. |

| Tadpoles |

Mature California Toad tadpoles

appear dark with light mottling while mature Arroyo Toad tadpoles appear light with dark mottling.

Arroyo Toad tadpoles tend to remain motionless more than California Toad tadpoles. About a quarter of a small group of California Toad tadpoles will be active at any moment, while only a few individuals in a small group of Arroyo Toad tadpoles will be moving at any moment.

Metamorphosing Arroyo Toad tadpoles show the pale V between the eyes, pale spots on the sacral humps, and yellow tubercles.

Metamorphosing California Toads are darker with no pale V or sacral hump coloring, and rust-colored tubercles. |

(From Sweet, 2010, 1 and 2)

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Active in daytime and at night. Often diurnal after winter emergence, becoming nocturnal in the summer after breeding.

|

| Movement |

| Slow moving, often with a walking or crawling motion along with short hops. |

| Defense |

| This toad uses poison secretions from

parotoid glands and warts to deter predators. Some predators are immune to the poison, and will consume toads. Still other predators such as ravens have learned to avoid the poisons by eating only their viscera through the stomach. |

Territoriality

|

| Male Western Toads are not territorial except when breeding. Amplexing males will kick away other males, and males may briefly fight other males at breeding sites. |

| Longevity |

| Western Toads in Colorado have been reported living at least 9 years. I have received a report of a toad raised from a tadpole that is 21 years old and still alive (9/14). |

| Voice (Listen) |

Most male California Toads do not have a pronounced vocal sac in which sound can resonate, so the volume of its calls is very low, which makes them not useful for attracting female toads at any great distance from the calling site. The calls are faint when compared to the loud calls of the sympatric Pacific Treefrog which usually share the breeding pond. But male toads do make a call during breeding aggregations. The call has been described as a high-pitched plinking

sound, like the peeping of a chick, repeated seveal times. The sound of a group of males calling has been compared to the sound of a distant

flock of geese.

Calls are produced at night and during the day during the short breeding season. Males make their call primarily when they are in close

contact with other males. Rather than being advertisement calls made to attract females, these calls are generally considered encounter or aggressive calls, or release calls, which serve to maintain territory and spacing between males. The calls may also serve other purposes - a lone

male toad has been observed calling.1 It could also be possible that female toads are attracted to the sounds of male encounter calls, and can judge a male's condition by his call, similar to the function of an advertisement call.

Unreceptive females may also produce a release call when grasped on the back by a male. Males and females sometimes make a release call when grabbed across the back by a human hand.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

Diet consists of a wide variety of invertebrates.

Prey is located by vision, then the toad lunges with a large sticky tongue to catch the prey and bring it into the mouth to eat.

Tadpoles consume algae and detritus, including the scavenged carrion of fish and other tadpoles

(including California Toad tadpoles - Herpetological Review 38(2), 2007 178-9)

|

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

Amplexus is axillary - the male grabs the female around her shoulders or armpits.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults (4 - 6 years old) come into breeding condition and migrate to ponds or ditches. Males and females pair up in axillary amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Breeding can occur any time from January to early July, depending on the elevation, winter snow levels, or rainfall amounts, taking place shortly after toads emerge from their hibernation sites and migrate to the breeding wetlands. Scent cues are used to find the way to the breeding site.

In some areas, breeding occurs after snowmelt when breeding ponds refill with water. Amplexus and egg-laying takes place in still or barely moving waters of seasonal pools, ponds, streams, and small lakes.

"Male arroyo toads have been observed in amplexus with small, late-breeding female western toads on three occasions; hybrid larvae hatch, but have massive deformities; most die by Gosner stage 25 (Sweet, 1992)."

AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 14 April 2020.

|

| Eggs |

Eggs are laid in long strings with double rows, averaging 5,200 eggs in a clutch.

Fresh eggs contain some of the toad's toxin to protect them from predation, but this poison decreases over time.

Eggs hatch in 3 to 10 days, often longer in the colder waters of higher elevations. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles are dark brown and grow to about 2.25 inches (5.6 cm) in length before undergoing metamorphosis.

Large schools of tadpoles often feed together in shallow water.

Tadpoles enter metamorphosis in 30 - 45 days, usually in summer or early fall, depending on water temperature - colder water delays metamorphosis.

In years of extreme winter weather, especially at higher elevations, metamorphosis might be only a few weeks before snow begins to accumulate again.

When in the process of metamorphosis, many tadpoles are often seen in aggregations at the edge of a pond in various stages of metamorphosis.

After most tadpoles undergo metamorphosis, large numbers of newly-transformed toads are often seen hopping around the edges of the water.

They may stay and spend the winter at the border of their natal wetland, or they may disperse to nearby sites away from the pond.

|

| Hybrids |

Hybridizes with A. canorus in the northern part of its range. (Stebbins 2003.)

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits a variety of habitats, including marshes, springs, creeks, small lakes, meadows, woodlands, forests, rice fields, and desert riparian areas.

In the spring and early summer, toads are often found at the edge of water, sometimes basking on rocks and logs. At other times of the year they are also found farther from the water where they spend much of their time in moist terrestrial habitats.

Toads use rodent holes, rock chambers, and root system hollow as refuges from heat and cold.

|

| Geographical Range |

The species Anaxyrus boreas is found in most of California, northern Baja Caifornia, Nevada, Idaho, western Montana, northern and central Utah, western and south central Wyoming, central Colorado, and extreme north central New Mexico, most of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, western Alberta, and extreme southeastern Alaska. Toads found in the Rocky Mountains have undergone a severe decline.

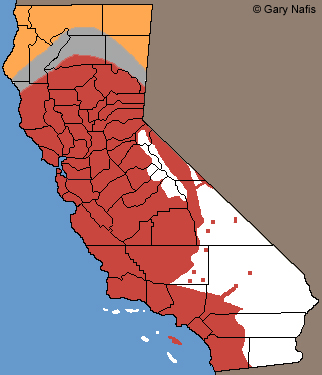

Range in California

The subspecies Anaxyrus boreas halophilus ranges throughout most of California, from the northern forests east barely into Nevada, and south through most of the state east of the deserts, into northern Baja California. Not present in most of the central high Sierra Nevada mountains where A. canorus is present, except south of Kaiser Pass, Fresno county. Present in isolated desert locations including Afton Canyon, Darwin Falls, Grapevine Canyon, the Newberry Mountains, Ridgecrest, the Borrego Valley and Coyote Creek, and Zzyzyx. They have also spread throughout some of the irrigated desert areas in Los Angeles County north of the mountains including the Antelope Valley, Palmdale, Apple Valley, Victorville, Oro Grande and other locations on the Mohave River, Rosamond, and California City, where the toads were probably introduced. A 2019 discovery extended the range well into the Mojave Desert in the Bighorn Wilderness north of Rimrock.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Anaxyrus boreas is found from sea level to over 11,800 ft. (3,600 m.) (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Formerly included in the genus Bufo, and Bufo is still used in many existing references.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 2006, Frost et al replaced the long-standing genus Bufo in North America with Anaxyrus, restricting Bufo to the eastern hemisphere.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Two subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas are traditionally recognized in California - Anaxyrus boreas halophilus, and Anaxyrus boreas boreas.

(Anaxyrus nelsoni has also been treated as a subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas: A. b. nelsoni, but this is controversial.)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List

does not recognize subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas:

"The English name of Boreal Toad is sometimes used broadly for this taxon, especially for populations sometimes referred to A. b. boreas (Baird and Girard, 1852), and refer Western Toad to A. b. halophilus. Two subspecies (A. b. boreas, A. b. halophilus) have been inconsistently recognized historically and we do not recognize them here given the substantial need for additional taxonomic work on this complex. The A. boreas group generally is considered to include a number of isolated populations that appear to be diagnosable as species. Some have been recognized as species and/or subspecies and others have no history of taxonomic recognition. From this complex, A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni are now generally accepted, and three additional allopatric populations have been named as species (A. monfontanus, A. nevadensis, and A. williamsi) recently have been described. Nevertheless, issues raised in older works by Cook (1983, Publications in Natural Sciences. National Museum of Canada: 89), Goebel (2005, in Lannoo, M. [editor], Amphibian Declines, University California Press: 210–211), Pauly (2008, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin), and Goebel et al. (2009, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 50: 209–225), using genetics, morphology, and advertisement calls, suggest that additional diversity remains unrecognized. The published genetic data used to investigate this group has been restricted to mitochondrial sequences, which have proven to be problematic in general (Dufresnes and Jablonski, 2022, Science 377: 127), and this complex is no exception. In such approaches, for example, the mitochondrial network and phylogenetic analyses of by Gordon et al. (2017, Zootaxa 4290: 123–139) found A. boreas to be paraphyletic with respect to A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni. Their work also suggests that the subspecies A. b. boreas and A. b. halophilus may be valid species, but Goebel et al. (op. cit.) found A. b. halophilus to be polyphyletic within the broader A. boreas group. A comprehensive review of the A. boreas group that includes nuclear DNA and dense geographic sampling is needed and likely will reveal a complex evolutionary history, and corresponding taxonomy, for this group that spans a considerably large and complex geographic region."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The SSAR 2017 names list does not recognize subpsecies of Anaxyrus boreas:

"Two nominal subspecies are generally recognized, although Goebel (2005, in Lannoo, M. J. [ed.], Amphibian Declines: the Conservation Status of United States Species. Univ. of California Press: 210–211) discussed geographic variation and phylogenetics of the A. boreas (as the Bufo boreas) group (i.e., A. boreas, A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni), and noted other unnamed populations of nominal A. boreas that may be species.

Populations in Alberta, Canada, assigned to A. boreas have a distinct breeding call and vocal sacs (Cook, 1983, Publ. Nat. Sci. Natl. Mus. Canada 3; Pauly 2008, PhD Dissertation, Univ. Texas at Austin); the taxonomic implications of this warrant investigation. Goebel et al. (2009, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50: 209–225) suggested on the basis of molecular evidence that nominal Anaxyrus boreas is a complex of species (as suggested previously by Bogert, 1960, The influence of sound on the behavior of amphibians and reptiles. Washington DC: American Institute of Biological Sciences 179) that do not conform to the traditional limits of taxonomic species and subspecies (and which we do not recognize here for this reason) and that some populations assigned to this taxon may actually be more closely related to Anaxyrus canorus and A. nelsoni—a problem that calls for additional elucidation. Reviewed by Muths and Nanjappa (2005, in Lannoo, M. J. [ed.], Amphibian Declines: the Conservation Status of United States Species. Univ. of California Press: 392–396) and Dodd (2013, Frogs of the United States and Canada, John Hopkins Univ. Press: 47–65). "

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The SSAR 2012 names list no longer recognized this or any subspecies of A. boreas:

"Goebel et al. (2009, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50: 209-225) suggested on the basis of molecular evidence that nominal Anaxyrus boreas is a complex of species (as suggested previously by Bogert, 1960, Animal Sounds Commun.: 179) that do not conform to the traditional limits of taxonomic species and subspecies (and which we do not recognize here for this reason) and that some populations assigned to this taxon may actually be more closely related to Anaxyrus canorus and A. nelsoni - a problem that calls for additional elucidation."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Toads at Haiwee Springs in the Coso Range, China Lake Naval Weapons Center Station, Inyo County, were found to be genetically separate enough from A. boreas (with similarities to A. nelsoni) to be considered at least a distinct population segment deserving of protection. (Lannoo 2005)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hybridizes with Anaxyrus canorus at Blue Lakes and with A. punctatus in Darwin Canyon and near Skinner Reservoir in Riverside County. (Stebbins and McGinnis 2013)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Toads in "Lone Pine, Owen's Valley, Calif." were considered Bufo nelsoni by Wright and Wright in 1949.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 2017, a new species was discovered within A. boreas in Nevada and named A. williamsi.

(Michelle R. Gordon, Eric T. Simandle & C. Richard Tracy. A diamond in the rough desert shrublands of the Great Basin in the Western United States: A new cryptic toad species (Amphibia: Bufonidae: Bufo (Anaxyrus)) discovered in Northern Nevada. Zootaxa 4290 (1): 123-139 © 2017 Magnolia Press.)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Anaxyrus boreas [no subspecies] (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Bufo boreas halophilus - California Toad (Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Bufo boreas halophilus - California Toad (Salt Marsh Frog, Baird's Toad, Common Toad) (Wright and Wright 1933-1949)

Bufo boreas halophilus - California Toad (Storer 1925)

Bufo boreas halophilus - California Toad - Barid's Toad, Common Toad, Salt-marsh Frog (Bufo boreas, part; Bufo chilensis; Bufo columbiensis, part; Bufo columbiensis halophilus; Bufo boreas nelsoni, part) (Grinnell and Camp 2017)

Bufo columbiensis (Cope 1889)

Bufo halophila (Baird and Girard 1853)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| Anaxyrus boreas is becoming uncommon in many areas of the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains and other areas, probably due to environmental changes caused by habitat loss, especially loss of wetlands, and chemical contamination of wetlands. Toads are also slow-moving and are frequently run over by traffic as they cross roads at night during their breeding migrations, which could also contribute to their loss. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Bufonidae |

True Toads |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Anaxyrus |

North American Toads |

Tschudi, 1845 |

| Species |

boreas |

Western Toad |

(Baird and Girard, 1852) |

| Subspecies |

halophilus |

California Toad

|

(Baird and Girard, 1853) |

| Original Description |

Bufo boreas Baird and Girard, 1852 - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 174

Bufo boreas halophilus Baird and Girard, 1853 California Toad

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

| Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Anaxyrus - Greek = A king or chief

Boreas - Greek = north wind or northern - which refers to the northern range

Halos - Greek = sea, salt

Philos - Greek = having an affinity for - refers to its coastal distribution

Taken in part from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

| Related or Similar California Frogs |

Anaxyrus boreas boreas

Anaxyrus californicus

Anaxyrus woodhousii

Anaxyrus canorus

Anaxyrus exsul

|

| More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This toad is not on the Special Animals List. There are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.`

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|