|

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, San Mateo County |

Adult, Butte County |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

Sub-adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Alameda County |

Adult, Stanislaus County |

|

|

|

|

| Calaveras County, © Diane Morrow |

Adult, Alameda County |

Adult male, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County. The color and pattern of some treefrogs helps them to blend into their surroundings to avoid detection. |

Adult in pond, Contra Costa County |

Adult in pond, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, 9000 ft. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Tuolumne County |

Adult, Siskiyou Mountains,

Siskiyou County |

Adult, Butte County

© Jackson Shedd |

Adult, Butte County

© Mela Garcia |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mariposa County. © Dr. Jean K. Krejca, Zara Environmental LLC |

Sub-adult, Monterey County

© Carla England |

Adult, Nevada County © Maxine |

Adult, Lassen County © Debbie Frost |

|

|

|

|

| Tan-chartreuse adult, Contra Costa County delta © Teejay ORear |

Adult, Sutter Buttes, Sutter County.

© Jackson Shedd.

Specimen courtesy of Eric Olson. |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County

© LJ Moore |

|

|

|

|

Adult, San Luis Obispo County

© Joel A. Germond |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County

© Joel A. Germond |

Two frogs found in the city of San Francisco, San Francisco County

© LJ Moore |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, just after jumping into the water, Contra Costa County |

Swimming adult,

Contra Costa County |

Adult frogs of assorted colors found above a door in Lassen County

© Debbie Frost |

|

|

|

|

| Foresters working on trees in the Presidio in San Francisco County, found this Sierran Treefrog under the bark of a Monterrey Cypress 40 feet above the ground. © Michael Riedel |

Sierran Treefrogs can wander far away from flowing or standing water after the breeding season. This one wandered up to the top of this rocky fire lookout at 6,700 feet elevation (2042 meters) in Sierra County where it was found in late July.

© Michael Gates

|

|

|

|

|

| This adult Sierran Treefrog was found at an old Native American bedrock mortar site. (Also seen in the water with it is a Horsehair Worm, and some Springtails.) These treefrogs will breed in almost any small pool of water if nothing larger is available, even mortar holes after they have filled with rainwater, in which eggs and tadpoles have been observed. |

Adult Sierran Treefrog and eggs in a large Native American bedrock mortar hole in Contra Costa County.

© Mark Gary |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Monterey County

© Gabriella Valdez |

Adult, Placer County

© Teejay O'Rear |

Using the enlarged pads on their toes, Treefrogs are excellent climbers. This one is hanging onto a glass car window.

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County, showing yellow "flash color" markings on the inner thighs. When the frog fears an attack from a predator, it jumps away, stretching the legs out and exposing the bright color. The predator automatically focuses on the bright color when it pursues the frog, but the color suddenly disappears when the frog lands and folds up its legs. This can confuse the predator long enough to allow the frog to escape. |

This shot of a frog floating in a Santa Clara County pond also shows the yellow "flash color" markings on the inner thighs. © Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

|

|

| These treefrogs have enlarged rounded toe pads that help them climb and can help you distinguish treefrogs from other types of frogs and toads. |

The toe pads are like little suction cups (seen here from underneath the toes.)

|

Dark stripes on the sides of the head from the eye to the shoulder help to identify this frog. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Sexual Dimorphism |

|

|

|

|

Adult female, showing light-colored skin under throat, Contra Costa County

|

Adult male, showing dark-colored skin under throat,

Contra Costa County |

|

| |

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| After undergoing metamorphosis from a tadpole to the adult form, juveniles usually hang around the edge of their birth pond or creek. Often you can see hundreds of them hopping around. These tiny Contra Costa juveniles are only approximately half an inch in length (12.7 mm). |

Recently transformed juvenile,

San Mateo County |

|

|

|

|

A pink and blue Juvenile, Yolo County © Lori Grennan

|

Thousands of these tiny metamorphs were seen around a small pond in Siskiyou County in August. |

|

|

|

|

A blue juvenile found in a squash blossom in El Dorado County

© Dennis Johnson |

Juvenile, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

|

|

| |

|

| Deformities |

Because of their thin permeable skin, amphibians are one of the first indicators of environmental disturbances, some of which can cause malformations as we see below.

More information about frog deformities and malformations. |

|

|

|

|

This recently-metamorphosed juvenile from Contra Costa County has a rear leg deformity that is most likely caused by a parasite that is hosted by a snail before it attaches itself to a tadpole. Such deformities are becoming more common and researchers are trying to determine if there are environmental factors which are favoring the parasites or which make the frogs more susceptible to them.

|

This juvenile treefrog from San Mateo County has a deformed fifth leg.

© Rory Doolin. |

|

| |

|

|

| Mating Season |

|

|

|

|

| Calling male, Contra Costa County |

Calling male, Contra Costa County |

Calling males, Contra Costa County |

Calling male with extended throat sack, Alpine County |

|

|

|

|

| Calling male, Alpine County |

Calling Male, Contra Costa County |

Calling Male, Alameda County |

© Joel A. Germond

A male Sierran Treefrog calls from the ceramic vat seen above trying to attract a female to mate with. |

|

|

|

|

| Adults in amplexus, Santa Clara County. © Bill Stagnaro |

Two males amplexing a female, Fresno County © Julie Nelson |

Eggs, Butte County |

Tadpole, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Sometimes during the mating season a male frog mistakes another species for a female of his species and grabs onto it in amplexus as this Sierran Treefrog is doing with a California Newt in Contra Costa County. © Mark Gary |

|

|

|

See more pictures of Sierran Treefrog eggs and tadpoles Here

|

| Predation |

|

|

|

|

A mature California Tiger Salamander larva eats a Sierran Treefrog tadpole.

© Mark Gary

|

This mature California Tiger Salamander larva is eating a Sierran Treefrog tadpole. © Mark Gary |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Contra Costa County creek |

Habitat, Contra Costa County creek |

Habitat, Alameda County pond |

Habitat, Butte County temporary pond |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, 500 ft, western

Stanislaus County creek

|

Pond habitat, San Mateo County |

Pond habitat, Contra Costa County

|

Lake habitat in breeding season,

8,800 ft., Alpine County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Monterey County pond |

Habitat, Mendocino County meadow |

Pond habitat, 4,500 ft.,

Kern County |

High-altitude wet meadow habitat,

9,000 ft, Sierra Nevada mountains,

Tuolumne County |

|

|

|

|

Pond habitat, 6,000 ft.

Siskiyou County. |

Habitat, flooded roadside above Klamath River, Siskiyou Mountains, Siskiyou County |

Pond habitat, 6500 ft., Warner Mountains, Modoc County |

Habitat, flooded meadow in spring during breeding season, 4,500 ft.

Siskiyou County |

|

|

|

|

Breeding habitat, roadside ditch next to creek, 1,100 ft. Fresno County.

|

Habitat, San Mateo County pond |

Seasonal pond used for breeding,

Contra Costa County.

Follow this link to see more pictures of this pond as it looked in different months (of different years) showing how the pond and its surroundings change over the seasons.

|

|

|

|

|

| Frogs were calling from this flooded ditch next to an agricultural canal in Merced County on a March afternoon. |

Habitat, snow-melt meadow pond at 9500 ft. elevation (2,900 m.) in the Sierra Nevada mountains in Inyo County. |

Breeding habitat, flooded field, Contra Costa County

© Grayson B. Sandy |

Breeding pond, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Woodland post-breeding habitat, Santa Clara County © Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| Three adult male Sierran Treefrogs make their advertisement call one afternoon in early March in Contra Costa County. |

In this short video we see three adult male Sierran Treefrogs make their trilled encounter call. The call of each frog is slightly different. I got the frogs to make these calls near the camera by imitating the encounter call when I was close to the frogs which were sitting on the water in calling position. |

A male Sierran Treefrog makes a few advertisement calls, until a second frog between him and the camera, makes a raspy trilled encounter call. The first frog responds with his encounter call, but when the second frog continues, he then turns to face his aggressor and charges toward him, continuing to make his encounter call. The second frog changes his call to a faster one part call. Finally they both stop, and the first frog sucks in his throat sac and dives underwater. |

An adult male Sierran Treefrog makes a one-part call while floating on the water on a sunny afternoon in Contra Costa County. |

|

|

|

|

| A male Sierran Treefrog makes the one-part or enhanced call from the edge of a small temporary snow-melt pond at 8,600 feet elevation in Alpine County. |

In this video we zoom out from a calling Sierran Treefrog to show an overview of his habitat in Contra Costa County. |

Thousands of recently-metamorphed Sierran treefrogs surround a tiny pond in the mountains of Siskiyou County. |

Recently-transformed Sierran treefrogs around the shores of their birth ponds. |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are .75 - 2 inches long from snout to vent (1.9 - 5.1 cm). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A small frog with a large head, large eyes, a slim waist, round pads on the toe tips, limited webbing between the toes, and a wide dark stripe through the middle of each eye that extends from the nostrils to the shoulders.

Legs are long and slender.

Skin is smooth and moist.

Often there is a Y-shaped marking between the eyes.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Dorsal body coloring is variable: green, tan, brown, gray, reddish, cream, but it is most often green or brown.

The underside is pale with yellow underneath the back legs.

Ability to Change Color

The dark eye stripe does not change, but the body color and dark markings can quickly change from dark to light, and the body color itself can also change, typically from brown to green or vice versa or a combination of both, in response to environmental conditions.

A study of Hyla (Pseuacris) regilla in Washington concluded that "H. regilla has control over and can change its hue, chroma, and lightness during time periods on the order of minutes." ..."...we support the idea that physiological color change has evolved as a mechanism to allow rapid background matching as a tree frog moves from one location to another."

(James C. Stegen et al. The control of color change in the Pacific tree frog, Hyla regilla. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2004, Vol. 82, No. 6)

|

| Male/Female Differences |

| The male's throat is darkened and wrinkled. |

| Young |

| Similar to adults. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are up to 1 7/8 inches long ( 4.7 cm) blackish to dark brown and light below with a bronze sheen.

The intestines are not visible.

Viewed from above, the eyes extend to the outline of the head.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Active both day and night, becoming mostly nocturnal during dry periods.

During wet weather, they move around in low vegetation. In locations at low elevations where temperatures are more moderate, frogs may be active all year. At colder or hotter locations, frogs avoid temperature extremes by hibernating in moist shelters such as dense vegetation, debris piles, crevices, mammal burrows, and even human buildings.

The name "treefrog" is not entirely accurate. This frog is chiefly a ground-dweller, living among shrubs and grass typically near water, but occasionally it can also be found climbing high in vegetation and on trees. Its large toe pads allow it to climb easily, and cling to branches, twigs, and grass.

Green body color absorbs more solar radiation which can be more beneficial in cold and aquatic habitats.

Brown body color absorbs less solar radiation, which may be more beneficial in drier, hotter, more terrestrial habitats. |

| Defense |

| When disturbed, this frog typically hops a large distance or jumps into the water and swims into vegetation to hide. But at times they will use their cryptic body color to avoid predation by remaining motionless. |

Territoriality

|

| Males are territorial during the breeding season, producing a slow trilled encounter call to warn other males. |

| Longevity |

| Not known. |

| Voice (Listen) |

Advertisement calls are heard during the evening and at night, and during the daytime at the peak of the breeding season.

Males produce two different kinds of very loud advertisement calls: a two-parted, or diphasic call, typically described as rib-it, or krek-ek, with the last syllable rising in inflection, and a one-part, or monophasic call, also called the enhanced mate attraction call.

They also produce a slow trilled encounter call, a release call, and a land call, which is a prolonged one-note sound that is produced much of the year, especially during the beginning of the fall rains.

The most commonly heard frog in its range.

(The call of the Baja California Treefrog is known throughout the world through its wide use as a nighttime background sound in old Hollywood movies, even those which are set in areas well outside the range of this frog. The call of the Baja California Treefrog is identical to that of the Sierran Treefrog and the Pacific Treefrog, and it is possible that the calls any of these species were used as movie sound effects.) |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats a wide variety of invertebrates, primarily on the ground at night, including a high percentage of flying insects.

During the breeding season, they also feed during the day.

Typical of most frogs, prey is located by vision, then the frog lunges with a large sticky tongue to catch the prey and bring it into the mouth to eat.

Tadpoles are suspension feeders, eating a variety of prey including algae, bacteria, protozoa and organic and inorganic debris. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and move to ponds or ditches where the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Breeding and egg-laying occurs between November until July, depending on the location.

Adults probably become reproductively mature in their first year. Mature adults come into breeding condition and move to ponds or ditches where the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. These calls attract more males, then eventually females. Males call while in or next to water at night, and during daylight during the peak of breeding when calling can occur all day and night.

Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Some males and females have been observed staying only a few weeks at a breeding site. Some males have been observed moving to another site. And others have been observed staying at a site the entire breeding season.

Males are territorial during the breeding season, establishing territories that they will defend with an encounter call or by physically butting and wrestling with another male. Satellite male breeding behavior has been observed - a silent male will intercept and mate with females that are attracted to the calling of other territorial males.

Breeding locations include slow streams, permanent and seasonal ponds, reservoirs, ditches, lakes, marshes, shallow vegetated wetlands, wet meadows, forested swamps, potholes, artificial ponds, and roadside ditches. The Baja California Treefrog tends to avoid large lakes or streams with very cold water. |

| Eggs |

Females lay on average between 400 - 750 eggs in small, loose, irregular clusters of 10 - 80 eggs each.

(Rorabaugh & Lannoo, Lannoo, 2005)

Egg clusters are attached to sticks, stems, or grass in quiet shallow water.

The eggs hatch in two to three weeks.

Eggs appear to be resistant to the negative effects of solar UV-B radiation and even to increased water acidification.

Eggs can also survive freezing temperatures for a short time.

|

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles aggregate for thermoregulation and to avoid predation.

Tadpoles metamorphose in about 2 to 2.5 months, generally from June to late August.

In summer, there are often large congregations of new metamorphs along the banks of breeding pools.

Metamorphosed juveniles leave their birth pond soon after transformation, dispersing into adult habitats.

|

| Habitat |

This species utilizes a wide variety of habitats, often far from water outside of the breeding season, including forest, woodland, chaparral, grassland, pastures, desert streams and oases, underground caves, rice fields, and urban areas.

|

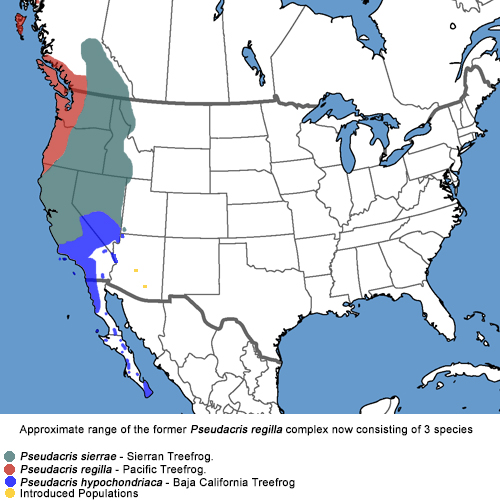

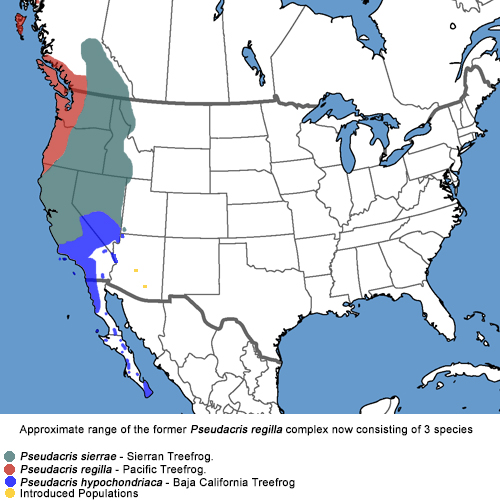

| Geographical Range |

The range of this species is not clear, due to the small number of specimens sampled for the study that described it as a new species in 2006. (see Taxonomic Notes below.) It is apparently found from Santa Barbara County north to Humboldt County, north of Bakersfield and northeast into most of Nevada, southeast Oregon, Idaho, and the extreme northwestern edge of Montana, then north into eastern British Columbia.

The southern contact zone with Pseudacris hypochondriaca and northern contact zone with Pseudacris regilla, are unlear. How far south it ranges into the southern San Joaquin Valley, the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the northern Owens Valley is unclear.

According to the U.S.G.S. online account, this species occurs all the way up the northern California coast into southwest Oregon (in the area where I show P. regilla occurring in California.)

Specific named localities in the 2006 Recuero et al study are:

San Luis Obispo County, Los Padres National Forest

San Luis Obispo County, Santa Margarita

Monterey County, McClusky Slough

Shasta County, Shingleton (Shingletown)

Alpine County, Highland Lakes

Tuolumne County, Kennedy Meadows

Missoula Co., Montana, Clark Fork River

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List comment:

"Jadin et al. (2021, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 132: 612–633) found that P. sierra rather than P. regilla is present in Idaho and Montana, thus greatly expanding the known range of P. sierra."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nonindigenous Populations Outside California

According to the USGS Nonindigenous Populations page (12/20) in 1983 two P. sierra were found at the Miami International Airport and in 1986 a gravid female P. sierra was found in Dover, Florida, both in shipments from a horticultural business in Santa Rosa, California. The potential continuing transport into Flordia or other states is a cause for concern.

Nonindiginous populations of P. regilla occur in Arizona in the Virgin Mountains and in plant nurseries in Phoenix and Tucson (Brenenan and Holycross 2006).

(P. regilla was split into three species, but which species occurs in Arizona is not known.)

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to 12.040 ft / 3,670 m. (Hansen & Shedd, 2025) (P. hypochondriaca, P. sierrae, and P. regilla are treated together as one species.)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Genus changed from Hyla to Pseudacris

The Generic name of this species was changed from Hyla (Treefrogs) to Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs). This creates confusion when some continue to use the long-used common name Treefrog, even though Chorus Frog is more accurate. Most authorities show the common name as either Treefrog or Chorus Frog, which I do here.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"We (actually the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, the Herpetologists' League, and the American Society of

Ichthyologists and Herpetologists) have decided it best to call our local loud mouths, the Pacific Treefrog, Pseudacris regilla.

So, we're going to acknowledge that the species is not a treefrog, it's a chorus frog. But, we're going to concede that the vernacular doesn't have to be an accurate reflection of phylogeny and go with the traditional, well-recognized name, Pacific Treefrog." Kelly McAllister, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The naming of this frog has been confusing for years, and in 2006 it got even more confusing when one species of frog was split into three species (see the information directly below.) I am using this three species taxonomy on this website because it has been adopted by some reputable Herpetological associations, but it is still not universally accepted. Some herpetologist believe that it is not accurate because there are no obvious differences in appearance or in the advertisement calls between the three species of frogs.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One species (Pseudacris regilla) becomes three species:

In 2006 Recuero et al published evidence that Pseudacris regilla is actually made up of 3 species. However, they assigned names to two of the species which they later determined were incorrect. The three species were correctly named in a followup paper.

((Recuero, Ernesto, Íñigo Martínez-Solano, Gabriela Parra-Olea, Mario García-París. Phylogeography of Pseudacris regilla (Anura: Hylidae) in western North America, with a proposal for a new taxonomic rearrangement 2006 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39: 293-304

Recuero, Ernesto, Íñigo Martínez-Solano, Gabriela Parra-Olea, Mario García-París. Corrigendum to ‘‘Phylogeography of Pseudacris regilla (Anura: Hylidae) in western North America, with a proposal for a new taxonomic rearrangement’’ [Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39 (2006) 293–304]

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41(2): pp. 511.))

The names they gave these three species are:

Pseudacris regilla - Northwest Chorus Frog

This is the northern clade, ranging along the north coast from approximately Humboldt County north into parts of Oregon and Washington.

Pseudacris sierra - Pacific Chorus Frog

This is the central clade, ranging approximately from Humboldt County south to Santa Barbara, and east into the Sierras, and the Northcentral, and Northeast part of the state, including Shasta County, and into Nevada, Eastern Oregon, Idaho and Montana.

Pseudacris hypochondriaca - Baja California Chorus Frog

This is the southern clade, ranging approximately from Santa Barbara south throughout Baja California, east to Bakersfield, Beatty, and southern Inyo County. This species is comprised of two subspecies, P. h. curta, which occurs in Baja California, and P. h. hypochondriaca, which occurs in California.

The authors do not provide detailed maps or descriptions of the ranges of the three species and they do not describe the contact zones between the species. They also do not provide any locality information for P. regilla, leaving me to consult previous work on the former subspecies Pseudacris regilla pacifica. This makes it hard to determine where these species occur in the state.

The dark spots on the following map are the approximate localities of the small sample of specimens used in the study. The colored areas are a guess at the range of each species. According a range map put online by the U.S.G.S., P. regilla does not even occur in California, but I have included it on my map because I believe the old subspecies P. r. pacifica ranged south along the north coast to Humboldt County, though I have no reference yet to back that up. It is possible that the species does not occur in California. Obviously, much more research is needed on these three species.

|

|

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The 2017 SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 43 (scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico) comments that

the three species may once again be regarded as only one species, Pseudacris regilla: "Barrow et al. (2014, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 75: 78–900) suggested that the distinction of P. hypochondriaca and P. sierra, drawn on the basis of mtDNA, was not supported by nDNA analysis. This suggests that this taxon will ultimately be included in the synonymy of Pseudacris regilla."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Genus Hyliola

In a paper published April 2016 * William E. Duellman, Angela B. Marion & S. Blair Hedges present a new phylogenetic tree of hylid frogs (Family Hylidae Rafinesque, 1815) that consists of three families, nine subfamilies, and six resurrected generic names and five new generic names. The family Hylidae contains 7 subfamiles, based on molecular information, not necessarily morphologic characters. Using this tree, the four hylid species found in California become part of the subfamily Acridinae (Acridinae Mivart, 1869) which contains two genera, Pseudacris, and Hyliola (Hyliola Mocquard, 1899.) Our treefrogs (formerly placed in the genus Pseudacris) are placed in the genus Hyliola:

Hyliola cadaverina (Cope),

Hyliola hypochondriaca (Hallowell),

Hyliola regilla (Baird and Girard) &

Hyliola sierra (Jameson, Mackey, and Richmond.)

* William E. Duellman, Angela B. Marion & S. Blair Hedges. Phylogenetics, classification, and biogeography of the treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae)

Zootaxa 4104 (1): 001–109 http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press.

Hansen and Shedd (2025) use Psedudacris with this comment: "...Duellman et al. (2016) recommended moving California species [of hylid frogs] to a third genus, Hyliola, based on their geographic separation from eastern members of Pseudacris, a move we find unnecessary and needlessly disruptive of now-established taxonomy. We follo wth reasoning of Faivovich et al. (2018) and Banker et al. (2020) in retaining use of Pseudacris."

Amphibiaweb (accessed January, 2025) uses the genus Pseudacris with the subgenus Hyliola.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List comment: on Hyliola

"Based on a re-analysis of previously published molecular data, Duellman et al. (2016, Zootaxa 4104: 1–109) restricted the name Pseudacris to the eastern and Rocky Mountain species related to P. nigrita and allocated the western species, P. cadaverina, P. hypochondriaca, P. regilla, and P. sierra to Hyliola Mocquard, 1899. Based on genome-wide nDNA data, Banker et al. (2020, Systematic Biology 69: 756–773) argued that Hyliola should not be recognized because (a) the genus Pseudacris already is a monophyletic taxon without the change, and (b) the geographic separation rationale cited by Duellman et al. (2016, Zootaxa 4104: 1–109) is insufficient as the sole criterion for splitting a long-recognized monophyletic clade, causing unnecessary taxonomic instability. Use of Hyliola has not gained any traction in the systematic community, presumably because of the small number of species involved." |

| |

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

The Genus of this species was changed from Hyla (Treefrogs) to Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs). This creates confusion when some continue to use Treefrog because it has been used for many years (as I do here, following the SSAR) while others use Chorus Frog, which is actually more accurate.

(See comments directly above on the use of yet another new genus Hyliola.)

To add to the confusion, these scientific and common names are all used for this frog in various websites and publications:

Pseudacris sierra - Sierran Treefrog

Pseudacris sierra - Sierran Chorus Frog

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Chorus Frog

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Treefrog

Hyla regilla - Pacific Treefrog

Pseudacris sierra - Sierran Treefrog (2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Pseudacris sierra - Sierran Treefrog (2025 CDFW)

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Chorus Frog (Hansen and Shedd 2025)

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Chorus Frog (McGinnis & Stebbins 2018)

Hyliola sierrae (Duellman, Marion, & Hedges 2016)

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Chorus Frog (Pacific Treefrog) (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Hyla regilla - Pacific Treefrog (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Hyla regilla - Pacific Tree-Frog (Stebbins 1954)

Hyla regilla - Pacific Tree Frog (Pacific Tree Toad, Pacific Hyla, Wood Frog, Pacific Coast Tree Toad) (Wright & Wright 1949)

Hyla regilla - Pacific Tree-toad (Storer 1925)

Hyla regilla - Pacific Tree-frog - Western Tree-frog, Wood-frog, Pacific Hyla, Tree-toad, Cadaverous Hyla, Greeny, Cape San Lucas Hyla (Litoria occidentalis; Hyla scapularis; Hyla nebulosa; Hyla scapularis var. hypochondriaca; Hyla cadaverina; Hyla regilla var. scapularis) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Hyla curta (Van Denburgh 1905)

Hyla scapularis (Hallowell 1854)

Hyla nebulosa (Hallowell 1854)

Hyla regilla (Baird & Girard 1852)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

This species is not considered to be declining in population.

Tadpoles are sensitive to nitrites and excess nitrite concentrations from agricultural runoff could cause them harm.

Diseases, pollution, parasites, and non-native predators can all be a threat to all frogs.

More information about frog deformities and malformations. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Hylidae |

Treefrogs |

Laurenti, 1768 |

| Genus |

Pseudacris |

Chorus Frogs |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

sierra |

Sierran Treefrog

|

(Jameson, Mackey, and Richmond, 1966) |

|

Original Description |

Hyla or Pseudacris regilla (Baird and Girard, 1852) - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 174

Recuero, Martinez-Solano, Parra-Olea, and García-París, 2006

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Pseudacris

Greek - pseudes = false, deceptive +

Greek - akris = locust

[Acris is also the genus of Cricket Frogs, which make a sound similar to a locust, so the name probably refers to this frog's call, which could be heard as similar to the sounds of locusts or Cricket Frogs.]

sierra - refers to the Sierra Nevada Mountains

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Pseudacris hypochondriaca - Baja California Treefrog

Pseudacris regilla - Pacific Treefrog

|

|

More Information and References |

U. S. Geological Survey (With maps and information about the 3 species split of the former Pseudacris regilla species.)

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

Recuero, Ernesto, Íñigo Martínez-Solano, Gabriela Parra-Olea, Mario García-París. Phylogeography of Pseudacris regilla (Anura: Hylidae) in western North America, with a proposal for a new taxonomic rearrangement 2006 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39: 293-304

Recuero, Ernesto, Íñigo Martínez-Solano, Gabriela Parra-Olea, Mario García-París. Corrigendum to ‘‘Phylogeography of Pseudacris regilla (Anura: Hylidae) in western North America, with a proposal for a new taxonomic rearrangement’’ [Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39 (2006) 293–304]

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41(2): pp. 511.

Brennan, Thomas C., and Andrew T. Holycross. Amphibians and Reptiles in Arizona. Arizona Game and Fish Department, 2006.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This frog is not included on the Special Animals List, meaning there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California according to the Dept. of Fish and Game.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|