|

This species has been introduced into California. It is not a native species.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Large adult female, San Diego County |

|

Large adult female with eye injury,

Imperial County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult female, Stanislaus County |

|

|

|

|

Underside of adult female,

Stanislaus County |

Adult male, Merced County |

Adult male, two adult females, and juvenile, Kings County

© Patrick Briggs |

Adult female, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Los Angeles County |

Adult male, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

Adult male, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

Adult, Orange County © Tadd Kraft |

|

|

|

|

Adult, San Francisco County

© Luke Talltree

|

Adult male, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

Adult male, Santa Clara County © Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

| Alameda County © Yuval Helfman |

Adult female, Monterey County

© Yuval Helfman |

Comparison of adult American Bullfrog tympanums (the round eardrum behind the eye).

The diameter of an adult male's tympanum (left) is larger than the diameter of the eye.

The diameter of an adult female's tympanum (right) is smaller than or equal to the diameter of the eye.

|

|

|

|

|

American Bullfrogs have large

webbed hind feet. |

Front toes do not have large pads

on the tips like treefrogs have. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

Juvenile, San Luis Obispo

County © Matt Willis |

Juvenile, San Luis Obispo

County © Matt Willis |

Juvenile, San Luis Obispo

County © Matt Willis |

Juvenile, Merced County |

|

|

|

|

Sub-adult, Stanislaus County

|

Juvenile, Fresno County © Jeff Ahrens |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, Santa Barbara County © Jeff Ahrens |

Transformed tadpole still with tail, just after leaving the water (left)

and two weeks later (right) More |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, easternmost Riverside County © Ryan Sikola |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Calling Male American Bullfrogs |

|

|

|

| Two males calling in daytime in Santa Clara County with small waves made by the vibrations of their throat sacs visible on the survace of the water. © Yuval Helfman |

Calling male at night in Arizona |

Calling male in daytime in Washington

(Short Video) |

| |

|

|

|

| Adult American Bullfrogs From Outside California |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Benton Co., Oregon |

Adult female, Refugio County, Texas |

Sub-adult, Adams County, Washington |

Juvenile male, Benton Co., Oregon |

|

|

|

|

Male calling at night from a lake in

Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

|

Adult Female, Yavapai County, Arizona |

Sub-adult, Bastrop County, Texas |

Adult male, Anne Arundel County, Maryland |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Maryland |

Skeleton of an adult American Bullfrog |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| American Bullfrog Feeding and Predation |

|

|

|

|

| Adult bullfrog eating a lesser goldfinch that came to drink in an artificial pond in Tehama County. © Lori Grennan |

A Diablo Range Gartersnake eating a Bullfrog tadpole in Santa Clara County. The snake regurgitated the tadpole. © Chad Lane

|

|

|

|

|

| Mature American Bullfrog tadpoles eating dead carp in a pond in Washington County, Oregon. © Chris Rombough |

|

|

|

|

Short Video

Mature American Bullfrog tadpoles eating dead carp in a pond in Washington County, Oregon.

© Chris Rombough

|

Adult male bullfrog swallowing a goldfish it found in an artificial pond in Tehama County

© Bonnie Kieley |

American Bullfrogs are voracious eaters that can impact native species, including threatened species like this Arroyo Toad and this Two-striped Gartersnake which were found in the belly of a large adult bullfrog in San Diego County. The snake was dead, but the toad was alive. When put back in the creek, it hopped away. A Bullfrog eradication project is now underway at the site where this was photographed.

© Andrew Borcher

Animals captured and handled under authorization by the Califoirnia Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| These pictures show an adult Giant Gartersnake eating an adult female American Bullfrog in Sutter County. © Richard Porter |

|

| |

|

|

|

Tadpoles and Froglets

|

|

|

|

| Mature tadpole, San Bernardino County |

Mature tadpole, Merced County |

|

|

|

|

|

Tailed metamorph, 1 day

after leaving the water |

Tailed metamorph, 3 days

after leaving the water |

Tailed metamorph, 5 days

after leaving the water |

|

You can see more pictures of American Bullfrog tadpoles,

and their development into frogs here.

|

| Unusually-patterned and colored American Bullfrogs |

|

|

|

|

| Melanistic adult American Bullfrog, Santa Clara County © Yuval Helfman |

Two melanistic sub-adults found in a Butte County pond.

© Roxanne Mulder |

This unusually pale bullfrog was found in Bakersfield, Kern County.

© Jose Casarez |

|

This Series Shows a Leucistic American Bullfrog Tadpole Found in Germany as it Changes Into a Frog Over a Period of 11 Months

All photos © Michael Waitzmann |

|

|

|

|

| Aquatic tadpole, 8/30/16 |

Aquatic tadpole, 9/03/16 |

Tailed metamorphosed froglet, 9/17/16 |

Froglet, 10/09/16 |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile frog, 06/23/17 |

Juvenile frog, 06/23/17 |

Juvenile frog, 07/16/17 |

Juvenile frog, 07/16/17 |

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, San Joaquin River,

Fresno County

|

Habitat, city lake, Los Angeles County |

Desert agricultural irrigation pond habitat, Riverside County |

Habitat, Irrigation canal,

Imperial County

|

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Yolo County canal |

Habitat, agricultural irrigation canal, Sacramento County |

Habitat, foothills creek, 500 ft.,

Stanislaus County |

Habitat, large artificial reservoir,

Fresno County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, large reservoir,

Contra Costa County

|

Habitat, pond, Marin County |

Tadpole habitat, Merced County

|

Habitat, creek, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Colorado River, Imperial County |

Habitat, river, Sacramento County

© Noah Morales |

Habitat, Alameda County

© Yuval Helfman |

Habitat, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, pools at the edge of a river, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| Views of several bullfrogs in ponds and creeks. |

Bullfrogs sitting around a crowded pond interact with each other, making chirping sounds and other noises. |

A bullfrog on the edge of a small pond tries to grab a bug with its tongue and fails, but succeeds on the second try, then jumps into the water to finish it off. |

Hundreds of bullfrogs make their frightened chirping sounds as they jump in and out of the water, or run across the surface to escape from danger. |

|

|

|

|

| Although they are quick to swim to the bottom when first approached, American Bullfrog tadpoles will usually calm down and resuface, where they slowly swim, float, and socialize. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Videos of Calling Male Bullfrogs |

|

|

|

|

A big male bullfrog calls from the edge of a lake in the daytime. He sat making single calls every few minutes, until suddenly lots of other bullfrogs began calling all around him and then he made longer series of calls. Here we see him start with a full series of calls, then wait a bit before making a second series of calls, but this time starting with some longer notes before doing his typical calls. There was a second male about 10 feet from him who was silent, but after this male makes his second full series of calls, the second male begins calling at 1 minute 10 seconds into the video. We can't see him, but he is about as loud as the first frog. You hear him when you can see that the first frog is silent. The second male's calling disturbed this frog so much, he made a short, sharp, territorial call and leaped in the air in the direction of the second frog. He landed closer to the second frog, but the second frog hadn't moved.

|

This is a very short version of the first series of calls heard in the long video shown on the left. |

This is also from the long video shown on the left - the short, sharp, territorial call made just before the frog leaps toward the other male. |

A large male Bullfrog calls at night from a lake in Santa Cruz County, Arizona. |

|

Description

|

| |

| Size |

The largest native frog inhabiting North America.

Adults are 3.5 - 8 inches long from snout to vent (8.9 - 20.3 cm). (Stebbins, 2003)

Males grow up to 7.09 inches long (18 cm), females up to 8 inches long (20.3 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A large frog with long legs and large webbed toes.

Dorsolateral folds are not present.

A short fold extends from the eye over and past the tympanum (eardrum) to the forearm.

The tympanum is conspicuous.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Light green to dark olive green, sometimes brown or tan, with dark spots and blotches.

Sometimes there is light green only on the upper jaw.

Cream to yellow below with grey marbling on larger individuals. |

| Male/Female Differences |

Males have tympanums larger than their eyes.

A female's tympanum is about the size of her eye.

Males also have a yellow throat.

The base of a male's thumb is swollen and dark.

|

| Young |

| Juveniles have many small dark spots. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are greenish yellow with small spots, growing up to 6 in. (15.3 cm).

|

| Comparing Red-legged Frogs and Yellow-legged Frogs and Bullfrogs |

| |

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

American Bullfrogs are highly aquatic - rarely found far from water.

Active day and night.

Prefers a relatively high body temperature and becomes active later in the spring in colder areas.

In areas with freezes in winter, bullfrogs hibernate under water, buried in mud or laying on a pond bottom.

|

| Movement |

Adults and juveniles are capable of hopping large distances.

Bullfrogs are very strong swimmers. |

| Defense |

When disturbed, they will hop into water and dive down, usually making a loud squeaking sound as they jump.

When captured they will sometimes play "possum" then suddenly jump away.

Bullfrogs and tadpoles are upalatable to many predators. |

Territoriality

|

Males defend their territory from other males during the breeding season.

A territorial sound is often used. |

| Longevity |

| Longevity in the wild is thought to be 8-10 years, but captive specimens have lived nearly 16 years. |

| Voice (Listen) |

The advertisement call is a loud low-pitched two-part drone or bellow, popularly described as "jug-o'rum." This is one of the loudest frog calls heard in California These calls are made during the day and at night.

Bullfrogs also produce an alarm call, a short fast squeak, which is usually made before the frog jumps into the water to escape from danger.

A short sharp "bonk" encounter call is also made.

A

loud open-mouthed screaming sound is made when a frog is under extreme stress, such as when it is being attacked or eaten by a snake.

An older female will sometimes vocalize along with males to let her better choose the most dominant male. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats anything it can swallow, including invertebrates, mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians including other bullfrogs.

Bullfrogs typically sit and wait for food to come near them, then they lunge after it. It is likely that bullfrogs also actively hunt other frogs after hearing their breeding or distress calls.

Tadpoles eat algae, aquatic plant matter, and some invertebrates. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Mating and egg laying occurs mostly from May to late August (but in some areas it occurs as early as March and as late as October.) Reproduction begins when the air temperature reaches a certain level (measured at one location in Kansas at 21 degrees C., or about 70 degrees F.)

Males are reproductively mature in 1-2 years, females in 2-3 years. (Lanoo, 2005)

Males set up a territory and make an advertisement call at night, but the call is also heard sometimes during the day.

Males defend their territory from other males.

Females choose a mate by entering a male's territory. An older female will also sometimes vocalize along with males, which creates more competition among the males, allowing the female to better choose the most dominant male. |

| Eggs |

Older females are capable of laying two clutches of eggs in a year.

A female may lay as many as 20,000 eggs and lose up to 27 percent of her body weight.

Eggs are laid in a sheet of jelly about 2 feet in diameter. The egg mass floats at first, then sinks to underwater vegetation just before hatching. Eggs hatch in 3 - 5 days. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles prefer areas of warm shallow water with dense aquatic vegetation. Transformed froglets are 2 in. (5 cm.) in length.

Bullfrog tadpoles are noxious to many species of fish who eat them only as a last resord, and they are probably probably noxious to some reptiles, birds and mammals.

Tadpoles enter metamorphosis anywhere from a few months after hatching in the warmer Southern parts of the United States to the end of their 2nd or 3rd summer in colder areas such as Michigan. In most of California, my guess (based on seeing many large old tadpoles in California) is that transformation probably

occurs after the second summer, but I don't know that for sure. It's possible they transform their first year in hotter areas or if they were hatched in temporary ponds.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits warm, sunny, open, permanent water - lakes, ponds, sloughs, reservoirs, marshes, slow river backwaters, irrigation canals, cattle tanks, and slow creeks. Found in grassland, farmland, including rice fields, prairies, woodland, chaparral, forests, foothills, and desert oases. Frequently inhabits artificial ponds and sometimes sealed swimming pools.

|

| Geographical Range |

Native Range

The species is native east of the Rocky Mountains throughout most of the midwestern, eastern and southern USA, reaching north barely into Canada, and south into eastern Mexico, and west to New Mexico and Colorado. The exact natural range of this species cannot be accurately determined because by the 1920's it had been introduced to frog farms outside of its natural range in order to use its large meaty legs for food, and escaped bullfrogs have become established throughout most of the western United States and southwestern Canada and Hawaii.

Global Range Introductions

American Bullfrogs have been introduced for food around the world. Some of the countries in which American Bullfrogs have been introduced include Mexico, Canada, Cuba, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela, Colombia, China, South Korea, and Japan.

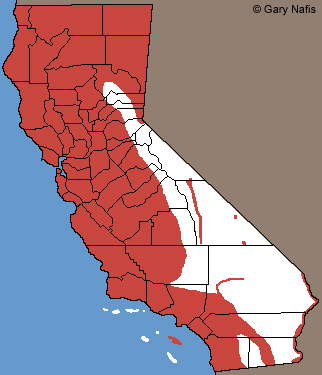

Introduced Range in California

American Bullfrogs are found throughout most of California, but they are absent from dry deserts and high elevations in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Widespread on Catalina Island.

American Bullfrogs appear to have been fairly isolated in their range in California in the 1920s, as indicated by the limited list of specimen record locations shown in Storer (1925), but bullfrogs spread quickly around the state afterwards. Storer indicates that "The Bullfrogs introduced into California have come from at least three sources. Those in Sonoma County were obtained from a dealer in New Orleans and presumably came from Louisiana; those introduced at Farmington were obtained in Missouri, while the frogs at Standard are said to have been obtained from a San Francisco dealer who purchased his stock in Hawaii." He states that the introduction was "done in the first instance by laymen intent upon adding a desirable species to our rather meager frog fauna..." which might be true, but bullfrogs were also introduced as food, specifically as a source of frog legs.

According to Stebbins & McGinnis (2012) American Bullfrogs were first introduced into California either in 1896 or in 1905 (both dates are used in the book) in order to use their legs as a food source. Bullfrog legs are nearly twice as large as the legs of the native California Red-legged Frog that had previously been used for food, so frog hunters concentrated on catching the rapidly-expanding bullfrogs instead of red-legged frogs, but since red-legged frog legs were considered to have a much better taste than bullfrog legs, both frogs continued to be hunted.

According to Tracy I. Storer, in "The Eastern Bullfrog in California" (California Fish and Game Volume 8, Number 4, October 1922) the term "French frogs" was commonly used throughout California for any frog large enough to eat, including California Red-legged Frogs and American Bullfrogs.

|

Red coloring on this map shows the Countries where American Bullfrogs have been introduced, not their exact range.

|

| Elevational Range |

Found at elevations from near sea level to about 9,000 ft. (2,740 m) in Colorado. (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 2006, Frost et al divided North American frogs of the family Ranidae into two genera, Lithobates and Rana. Rana is still used in most existing references.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Rana catesbeina - American Bullfrog (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Rana catesbeina - Bullfrog (American Bullfrog) (Stebbins 2003)

Rana catesbeina - Bullfrog (Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

Rana catesbeina - Bullfrog (Bloody Nouns, Bully, Jug-o' Rum, North American Bullfrog, American Bullfrog) (Wright & Wright 1949)

Rana catesbeina - Eastern Bullfrog (Storer 1925)

Rana catesbeina (Shaw 1802)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

The non-native American Bullfrog is probably responsible for some of the decline of many native species, including frogs, turtles, snakes, and waterfowl, which cannot compete with it or fall prey to it. Since bullfrogs evolved in habitats with a diverse number of predatory fish, unlike many California frog species, they probably have a competive advantage over native amphibians in areas where non-native fish are present. Bullfrog tadpoles are noxious to many species of fish which greatly increases their chance of survival. Bullfrogs also do well in areas disturbed by humans and in artificial wetland habitats such as farm and golf course ponds, unlike most native California frogs. Further introduction to waters where they are not present, should be prohibited and methods of eradication from waters where bullfrogs coexist with native amphibians should be studied and implemented if feasible. Bullfrog tadpoles were (and maybe still are) common in the pet trade in California. Once they transform and growinto frogs, making their care requirements more complicated, many of them are probably released into the wild.

This frog was included on the 2014 Global Invasive Species Database list of the 100 worst invasive alien species.

In their native range, bullfrogs are experiencing some decline with habitat loss, habitat alteration, chemical contamination, and over-harvesting for food.

A 2010 study of part of the Trinity River in California1 concluded that extensive human modifications of the river system have caused it to support American Bullfrogs to the detriment of native amphibian species, and that restoring the river to a more natural state should help to control the bullfrogs and improve conditions for native amphibians.

1 Fuller, T. E., Pope, K. L., Ashton, D. T. and Welsh, H. H. (2011), Linking the Distribution of an Invasive Amphibian (Rana catesbeiana) to Habitat Conditions in a Managed River System in Northern California. Restoration Ecology, 19:204213.

A 2009 study2 has documented male Rana draytonii in amplexus with juvenile American Bullfrogs and has proposed that this causes reproductive interference by the invasive species which could cause a reduction in the population growth rate of Rana draytonii since these males no longer call to attract females which causes fewer females to attempt to breed at the site, and because males engaged in amplexus are at greater risk of predation. And it raises the possibility that male Rana draytonii will find the smaller female Rana draytonii unattractive, leaving them without mates. This preference by the males leads them into an "evolutionary trap." 2 D'Amore, Antonia, Erik Kirby and Valentine Hemingway. Reproductive Interference By An Invasive Species: An Evolutionary Trap? Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(3):325-330. Submitted: 2 September 2008; Accepted: 9 November 2009. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Ranidae |

True Frogs |

Rafinesque, 1814 |

| Genus |

Lithobates |

American Water Frogs |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

catesbeianus |

American Bullfrog

|

Shaw, 1802 |

|

Original Description |

Shaw, 1802 - Gen. Zool., Vol. 3, Pt. 1, p. 106, pl. 33

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Lithobates - Greek

- Litho = a stone, bates = one that walks or haunts

catesbeianus - honors Catesby, Mark

Taken in part from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Lithobates berlandieri

Lithobates pipiens

Lithobates yavapaiensis

Rana draytonii

Rana aurora

Rana boylii

Rana cascadae

Rana pretiosa

Rana muscosa

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Conant, Roger, and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians Eastern and Central North America.

Third Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of Califonia Publications in Zoology Volume 27, The University of California Press, 1925.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This frog is not included on the Special Animals List, meaning there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California according to the California Department of Fish and Game.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|