|

|

| Adult, Alpine County |

|

|

|

| Adult, Alpine County |

Adult, Alpine County |

Juvenile, Alpine County |

|

|

|

| Adult, Alpine County (missing the fingers on its right hand) |

Adult, Plumas County

© Alan Barron |

|

|

|

| Adult, Warner Mountains, Modoc County © William Flaxington |

Adult, Warner Mountains, Modoc County © William Flaxington |

Adult, Butte County

© Mela Garcia |

|

|

|

Adult, Nevada County

© Chad Lane |

Sub-Adult, Nevada County

© Chad Lane |

|

|

|

Normally-colored adult on top

Melanistic adult on bottom

Alpine County |

Adult, Tuolumne County

© Emile Bado |

Adult, Shasta County

© Hannah Cooper |

|

|

|

| © Spencer Riffle |

An elongated toe (number 4) on each hind foot is the "long toe" that gives this species its common name. |

|

| |

|

|

| Long-toed Salamander Feeding |

|

|

|

| |

Oregon adult eating an earthworm |

|

| |

|

|

| Larvae |

|

|

|

| Mature aquatic larva, Siskiyou County. |

|

|

|

| Mature larva, with legs tucked in for swimming, Siskiyou County |

Mature Larva, Alpine County |

Mature larva eating a Boreal Toad tadpole, 5,800 ft. Shasta County

© Ryan Aberg |

| |

|

|

| Aberrant Larvae |

|

|

|

"Blonde" larva, about 8,300 feet elevation (2530 m.) Nevada County

© Carrie Johnson |

|

| |

|

|

More Pictures of Long-toed Salamander Eggs, Larvae, and Young

|

| |

| Habitat |

|

|

|

Breeding pond, late Spring,

8,300 ft., Alpine County

|

Breeding pond, late Spring,

8,500 ft., Alpine County |

Breeding pond in July,

8,400 ft., Alpine County |

|

|

|

Breeding pond, still frozen in July 2006,

Alpine County |

Breeding pond, mid June 2004,

8,500 ft., Alpine County |

Breeding pond, mid June,

8,500 ft., Alpine County |

|

|

|

Breeding pond, mid June,

8,500 ft., Alpine County |

Breeding pond, late Spring,

8,400 ft., Alpine County |

Breeding pond, still frozen in July 2006,

Alpine County |

| |

|

|

| |

Breeding pond in September,

6,000 ft. Siskiyou County.

|

|

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

A larval Southern Long-toed salamander swims around in an aquarium, using its legs, body and tail to propel itself.

|

Larval Southern Long-toed salamanders swim around in a pond in a forest clearing on a sunny September day in Siskiyou County. |

A larval long-toed salamander in a pond in Siskiyou County. |

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 1 3/5 to 3 1/2 inches long (4.1 - 8.9 cm) from snout to vent, 4 to 6 2/3 inches (10 - 17 cm) in total length.

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized salamander.

The body is stout with 12 - 13 costal grooves and a broad rounded head, a blunt snout, small protuberant eyes, and no nasolabial grooves.

The tail is flattened from side to side to facilitate swimming.

Large untransformed aquatic adults have gills on either side of the head. |

| Color and Pattern |

| Dusky or black above with a yellow dorsal stripe, usually interrupted by dark blotches. The sides are sprinkled with whitish specks. The venter is grey or black. |

| Young |

Larvae have broad heads, three pairs of bushy gills and broad caudal fins that extend well onto the back.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

A member of the Mole Salamander family (Ambystomatidae) whose members are medium to large in size with heavy, stocky bodies.

Ambystomatid salamanders have two distinct life phases:

- Larvae hatch from eggs laid in water where they swim using an enlarged tail fin and breathe with filamentous external gills. - Aquatic larvae transform into four-legged salamanders that live on the ground and breathe air with lungs.

Transformed adults are terrestrial and breathe with lungs but some gilled adults remain in the water and grow to a large size before transforming. However, neotenic adults have not been reported. |

| Activity |

Adults spend much of their lives underground, often utilizing the tunnels of burrowing mammals such as moles and ground squirrels.

Transformed adults are rarely found outside of the breeding season.

They are mostly found under wood, logs, rocks, bark and other objects near breeding sites which can include ponds, lakes, and streams, or when they are breeding in the water. At other times of the year they stay in rotten logs or moist places underground such as animal burrows.

Adults and juveniles migrate to breeding sites in Winter and Spring, and again to wintering locations in the fall. Larvae slow down their activity and winter under the ice resting under debris on the bottom of the water.

At some low-elevation locations (typically not in California) they may remain active all year. |

| Longevity |

| Adults live to about 10 years of age. |

| Sound |

| Adult Long-toed Salamanders can vocalize with squeaks and clicks, which might startle predators who capture them. (Hossack, B. R. 2002. natural history notes: Ambystoma macrodactylum krausei (northern long-toed salamander). Vocalization. Herpetological Review 33:121.) |

| Defense |

| Adults produce sticky skin secretions to deter predators. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Carnivorous.

Transformed adults eat small invertebrates, including worms, mollusks, insects, and spiders.

Larvae start by eating small crustaceans. As they increase in size, they gradually consume larger prey items, including crustaceans, worms, mollusks, and frog tadpoles.

Larger larvae may cannibalize smaller larvae.

Young larvae feed by sitting and waiting for prey, while larger larvae also stalk and pursue prey.

|

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Breeding occurs in permanent or temporary ponds, lakes and flooded meadows.

Adults become sexually mature at 1 - 3 years, and migrate overland from wintering sites to the breeding site in spring and early summer or later in years with a heavy snowpack.

Adults sometimes enter ponds not yet free of ice.

(In Oregon, Long-toed Salamanders may migrate to ponds in October and November.

Males enter the ponds before females.

Females spend approximately 3 weeks at a breeding site, but individual females only stay at the site for 1 - 2 days, and do not feed there.

Males feed at breeding sites, so they can stay at the site for the entire breeding season, which may last 2 months or more. |

| Eggs |

Females lay from 90 - 400 eggs in clusters containing from 1 - 81 eggs in shallow water, attaching them singly or in loose clusters to the undersides of logs and branches, or leaving them unattached on the bottom.

Eggs hatch in 2 - 5 weeks.

|

| Young |

Larvae transform at different rates depending on temperature and the permanence of the pool.

Transformation may take 4 - 5 months in temporary ponds, but larvae may overwinter in permanent ponds. In high elevation ponds, larvae may not transform until their second or third season.

After transformation transformed larvae disperse away from the breeding site.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits alpine meadows, high mountain ponds and lakes.

|

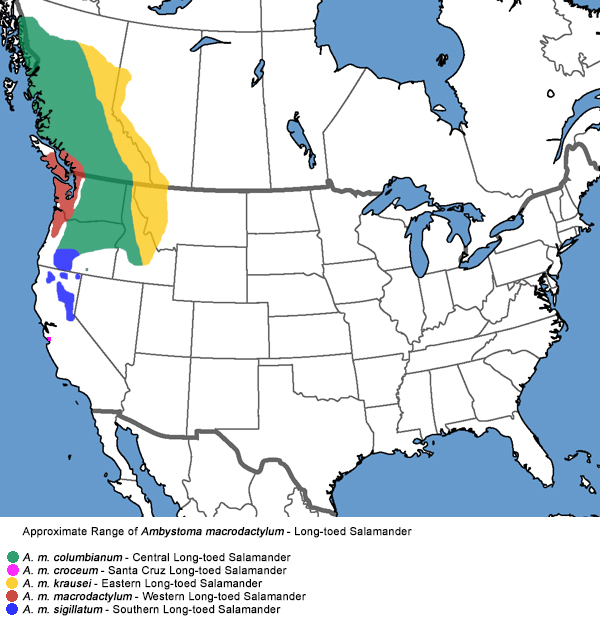

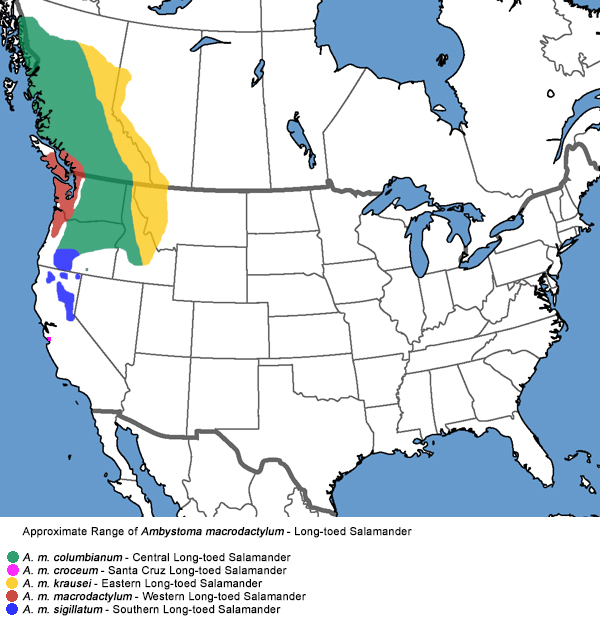

| Geographical Range |

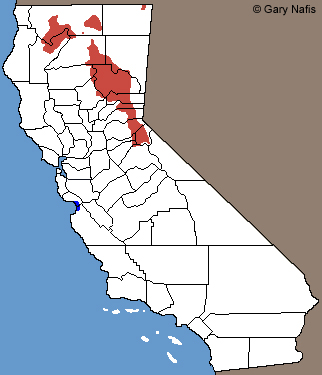

In California, this subspecies, Ambystoma macrodactylum sigillatum - Southern Long-toed Salamander, occurs in the Northeast and along the northern Sierra Nevada south to Garner Meadows and Spicer Reservoir, and in Trinity and Siskiyou Counties near the Trinity Alps. It also occurs in southwestern Oregon.

The species Ambystoma macrodactylum - Long-toed Salamander, is widespread in the west, occurring in California, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, western Canada, and Southeast Alaska.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Found at elevations up to about 10,000 ft.

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Five subspecies of Ambysoma macrodactylum are traditionally recognized, two occur in California:

A. m. sigillatum

A. m. croceum.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Lee-Yaw and Irwin (2012, Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 25: 2276–2287) and Lee-Yaw et al. (2014, Molecular Ecology 23: 4590–4602) evaluated geographic variation of mtDNA and nuclear genes throughout the range of the species and found the distributions of five lineages did not completely agree with those of the five presently recognized subspecies but suggested no changes in the taxonomy of the species. Raffaëlli (2022, Salamanders & Newts of the World. Plumelec, Penclen) continued to recognize the five subspecies."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A 2015 study by Lee-Yaw and Irwin has identified a sixth distinct group in the Central Oregon highlands, but suggested no changes in the taxonomy of the species. (You can see this new group and my estimate of the ranges of all the subspecies described in the paper HERE.)

(J. A. Lee-Yaw & D. E. Irwin. The mportance (or lack thereof) of niche divergence to the maintenance of a northern species complex: the case of the long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum Baird) Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28 (2015) 917-930)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Ambystoma macrodactylum sigillatum - Southern Long-toed Salamander (Stebbins 1966, 1985, 2003, 2012)

Ambystoma macrodactylum - Long-toed Salamander (Storer 1925, Bishop 1943, Stebbins 1954)

Ambystoma macrodactylum - Long-toed Salamander - Flat-footed Salamander (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Ambystoma macrodactyla (Baird 1850)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

This salamander does not appear to be in decline, however some populations might be at risk due to introduced fish and deforestation. UV-B radiation is another possible threat to high-altitude populations.

Protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Ambystomatidae |

Mole Salamanders |

Gray, 1850 |

| Genus |

Ambystoma |

Mole Salamanders |

Tschudi, 1838 |

| Species |

macrodactylum |

Long-toed Salamander |

Baird, 1849 |

Subspecies

|

sigillatum |

Southern Long-toed Salamander |

Ferguson, 1961 |

|

Original Description |

Ambystoma macrodactylum - Baird, 1849 - Journ. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Ser. 2, Vol. 1, p. 292

Ambystoma macrodactylum sigillatum - Ferguson, 1961 - Amer. Midland Nat., Vol. 65, 1961, p. 316

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

1.

Genus: Ambystoma, Greek - amby = round, like the rounded top of a cup + stoma = mouth — poss. ref. large rounded mouth

Steve Bledsoe, Southwestern Center for Herpetological Research

Ref. Ellen Beltz 2006

Ref. E. Jaeger 1962

2.

Ambystoma - Greek - amblys = blunt + stoma = mouth

macrodactylum - Greek = long toe

sigillatum - Latin = adorned with images or figures, referring to the color pattern

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Alternate Names |

None

|

|

Related or Similar California Salamanders |

Santa Cruz Long-toed salamander

California Tiger Salamander

Western Long-toed Salamander

Central Long-toed Salamander

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G5

T4 |

Species: Secure

Subspecies: Apparently Secure

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2 |

Imperiled |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

California Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|

Red: Range of this subspecies in California

Red: Range of this subspecies in California