Western Fence Lizard - Sceloporus occidentalis

Great Basin Fence Lizard - Sceloporus occidentalis longipes

Baird, 1859 “1858”Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

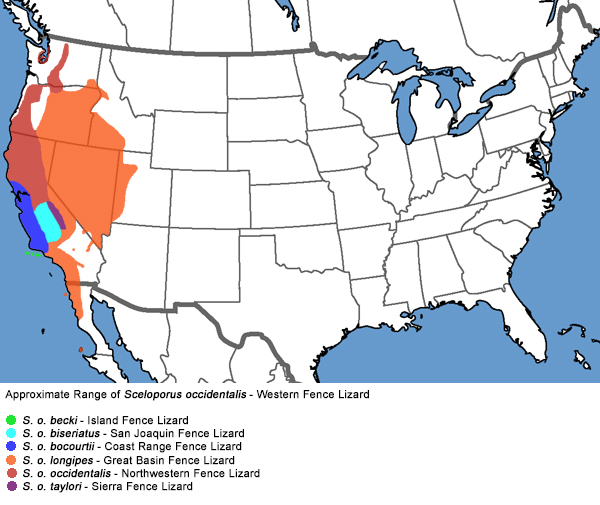

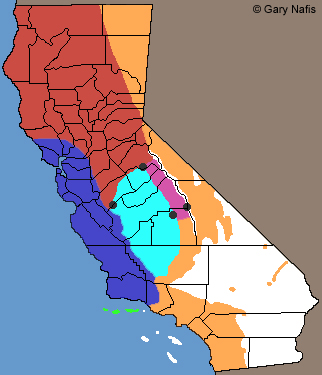

Orange: Range of this subspecies in California

Orange: Range of this subspecies in CaliforniaSceloporus occidentalis longipes -

Great Basin Fence Lizard

Range of other subspecies in California:

Bright Green: Sceloporus occidentalis becki -

Island Fence Lizard

Bright Blue: Sceloporus occidentalis biseriatus -

San Joaquin Fence Lizard

Dark Blue: Sceloporus occidentalis bocourtii -

Coast Range Fence Lizard

Red: Sceloporus occidentalis occidentalis -

Northwestern Fence Lizard

Purple: Sceloporus occidentalis taylori -

Sierra Fence Lizard

Dark Gray: Hybrid Zones

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County | Adult male, Inyo County | Adult female, Inyo County | Adult female, Los Angeles County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, 5,500 ft., San Diego County | Adult female, Inyo County © John Sullivan |

Adult male, San Diego County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, 7,300 ft. Mono County | Adult, Inyo County | Young male, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Mono County © Keith Condon |

Adult male, Modoc County | Adult male,1600 ft. San Gabriel Mountains foothills, Los Angeles County © Lori Paul |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, 9,300 ft. White Mountains, Inyo County | Adult female, Orange County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County | Young male, San Diego County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pale adult female, Lassen County. © Debbie Frost | Adult, Inyo County | Adult female, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Steve Bledsoe | Adult male, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon | Adult male, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

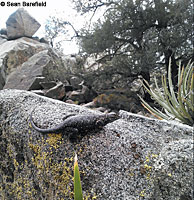

| Adult, New York Mountains, San Bernardino County © Sean Barefield | Adult, Granite Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

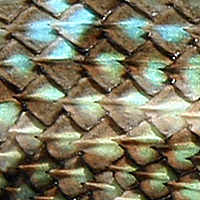

| Western Fence Lizards have overlapping keeled scales with spines on them over much of their body. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Los Angeles County |

Hatchlings, San Diego County © Shelly Hancock | Hatchling, San Diego County © Ketarah Shaffer |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| These hatchlings may have hatched from the nest in a San Diego County yard shown below. They were photographed near the nest site in September. © Connie McDowell |

This picture shows the difference in color and pattern between an adult female Side-blotched lizard (above) and juvenile Western Fence Lizards (below) © Mark Miller | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Mono County © Keith Condon | Juvenile, Orange County © Juan Carlos Tecson Gonzalez |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Color and Pattern Variations |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dark-phase adult male, Riverside Co. © Guntram Deichsel |

Dark-phase adult, San Bernardino County |

Dark-phase adult, San Bernardino County © Bo Zaremba |

Adult, Inyo Mountains, Inyo County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The three lizards shown above were photographed in mountainous areas in the northern part of Joshua Tree National Park, where the dark phase appears to be common. Other dark-phase lizards from desert mountains are shown in the main photo section above from the Kingston, Granite, and New York Mountains. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female from Orange County coast, showing yellow coloring on sides and armpits. © Beverly Gandall | Two adults, most likely females, with yellow markings, from the Palos Verdes Peninsula, Los Angeles County © Jonathan Hakim | © Patrick Briggs Unusual striped fence lizard from San Bernardino County, where a striped form occurs among populations of normally-patterned fence lizards. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This unusually pale adult found in Orange County appears to be missing some of the typical dark pigment. (That's a San Diego Alligator Lizard behind it sharing its territory.) © Jacob H. Lloyd Davies | This is the same lizard shown to the left, photographed about 5 weeks later. It looks even paler now. The lack of color appears to be genetic on this individual, but it would be leucistic, not albino, since the eyes are dark. © Jacob H. Lloyd Davies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Riverside County with unusually bright white scales. © Cody Merylees | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rusty-Orange or Yellow Great Basin Fence Lizards (and other unusual skin coloring ) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I have been sent quite a few pictures of spiny lizards that appear to have an unnatural color painted on them, some of which you can see below. Most are rusty-orange or yellow, but some are white or gray or bluish. These are most likely not naturally-occurring aberrant pigments, though that is sometimes observed, as you can see above. These unnatural colors are most likely from human-made substances such as paint or rust or some other chemical. These substances may be added to the lizard in a place where it takes shelter or overwinters. (Someone sent me pictures of a gray lizard that we figured out was colored by paint recently used on her house.) Most of these lizards are Great Basin Fence Lizards, probably because they are common lizards that live among humans in the most populated areas of the state and are easily observed. Living among humans makes them more likely to become contaminated by paint or chemicals. If an artificial color has been added to the lizard's skin it should fade with time and disappear when the skin is shed. This was observed on a bright orange lizard that was regularly seen at public gardens in Pasadena. The same lizard was observed a few months later with the color faded considerably, indicating that the color was added to the skin and not a natural pigment. Other lizards show signs of the skin peeling away the added color. However, some of these lizards were found in undeveloped open space where human-used chemical contamination is not as likely a cause. It has been suggested that these lizards might be covered with fungal spores or pollen. I received one report of orange-yellow fence lizards that were captured in California that were covered with something resembling spores or pollen that was easily brushed off, which confirms that theory. Unfortunately, I don't have pictures of them to confirm that. A similarly-colored orange American Alligator was seen in South Carolina. It was suggested that it might have overwintered in a rusty culvert pipe where the rust gave it the color, but again, that was just one theory. USA Today 2/10/17. You can see more pictures of similar unusually-colored spiny lizards on this page. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This apparent fence lizard was found in May in the San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles County. © Michael DeMarquette. |

This is another apparent adult fence lizard with a rusty-orange coloration that was found in late February in the Santa Monica Mountains of Los Angeles County. © Dana Duncan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is another adult from Los Angeles County with rusty coloring, photographed in mid February © Max Roberts | This unusual pale yellow Great Basin Fence Lizard was photographed in a yard in San Diego County in early May. © Rosanne |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This rusty-colored adult was found in the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles County in late March. © James Hess | © Elysia Hodges This adult was found in Orange County. It's not orange or yellowish like the others, it has some sort of white substance on much of its body. You can see some skin shedding from the nose, and part of the head is the normal color where the skin that was painted white has been shed. In a picture taken a few days earlier the lizard's head was completely white. |

Adult, observed in mid March on a trail in Orange County. © Austin Xu A herpetologist suggested that this lizard might have been covered in fungal spores. It's not clear if he was talking about Yellow Fungus Disease (aka CANV) which sometimes afflicts captive lizards, but this lizard and the others in this section all appear to be in good health and living in clean habitats, which makes that disease an unlikely cause of the unusual coloring. Nevertheless it's an interesting theory for the color. You can read more comments about this lizard at its observation page on iNaturalist. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| © Roger Hatton This bright orange lizard was observed in Los Angeles County in late March. The person who reported it knows and has handled fence lizards and describes the color as the color of the skin, not a color that was added. If the color is part of the skin itself then the unusual appearance might be due to piebaldism - scattered normal and abnormal pigment areas, which would explain the dark head and the other dark areas. That would make it a more natural aberration that what appears to he happening with most of the other lizards here, but the cause of the coloring is still not known. |

© Roger Hatton Two weeks later the lizard shown to the left appears a bit duller in color and a little "dustier" looking when in the shade, which might indicate that it is indeed covered with some substance that gives it the orange color. We can also see that he is a male, and now during the breeding season he has been observed interacting with females who apparently don't mind his unusual appearance. Three months after receiving this picture I was told that the lizard had slowly faded even more. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This unusually silver-blue-colored Great Basin Fence Lizard was found in San Diego County. © Ralph Petrozello | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nesting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A female fence lizard lays her eggs in a nest she dug on a San Diego County patio in mid June. © Connie McDowell |

This hatchling lizard was found near the nest site in September. It may have hatched from eggs deposited there. More pictures of hatchling lizards found near this nest are shown above in the "Juveniles" section. © Connie McDowell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gravid adult female fence lizard in San Diego County in late May digging in loose dirt that had been recently dug up, most likely to use as a place to lay her eggs. |

The location where the lizard was digging as it looked the following day, after she apparently concealed the location by packing the dirt over the eggs and re-arranging the vegetation. (Her activity was not observed, only the results.) © Bill Bachman |

This is the overall location of the San Diego backyard where the fence lizard dug her nest. © Bill Bachman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male Displays and Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two males fighting over territory in May in the San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County. The winner claims the rock - far right. © Mike Dorsey |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male territorial display. © Jason Rojas |

Two adult males fighting in April, San Bernardino County. © Jason Rojas |

Adult male in defensive display during breeding season, Los Angeles County. © Nao Rains |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-adult with throat display 6,000 ft. Inyo County | Adult male defensive display, Los Angeles County. © Douglas S. Brown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two adult males in spectacular breeding colors fight over territory in April in Los Angeles County. © Douglas S. Brown To see the full series of pictures of the battle, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This short video shows two male Great Basin Fence Lizards fighting over territory, biting on to each other's mouth. San Diego County © Stan Budz | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predation, Parasites, and other Dangers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Adult male with ticks on the side of his head. In California, western black-legged ticks (deer ticks) are the primary carriers of Lyme disease. Very tiny nymphal deer ticks are more likely to carry the disease than adults. A protein in the blood of Western Fence Lizards kills the bacterium in these nymphal ticks when they attach themselves to a lizard and ingest the lizard's blood. This could explain why Lyme disease is less common in California than it is in some areas such as the Northeastern states, where it is epidemic. |

Sean Kelly © shot this series of a California Striped Racer eating a male Great Basin Fence lizard in San Diego County. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| California Striped Racers eat mosly lizards. This one is swallowing a Western Fence Lizard while holding the front third of its body straight up off the ground. This racer usually hunts with its head in this elevated position. | Juvenile Pacific Gopher Snake eating a Western Fence Lizard © Daniel Harris | Juvenile fence lizards are preyed upon by many other animals, including the black widow spider. © Rory Doolin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sean Kelly found this juvenile Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake eating a Great Basin Fence Lizard behind his garbage can one afternoon in San Diego County. © Sean Kelly |

A California Striped Racer swallows a male Northwestern Fence Lizard in El Dorado County © Jim Bennett |

This adult was rescued from synthetic mesh fencing in which it was trapped in San Diego County. © Mark Miller | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Inyo County | Habitat, coastal San Diego County | Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County |

Habitat, Santa Ana Mountains, Riverside County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Sierra foothills, Kern County |

Habitat,6,200 ft. San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County | Habitat, Mohave Desert, San Bernardino County |

Habitat, Laguna Mountains, San Diego County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, 6,000 ft. Inyo County | Habitat, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Steve Bledsoe | Habitat, Tehachapi Mountains, Kern County |

Habitat, riparian zone at edge of San Bernardino mountains and Mohave Desert. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult in habitat, Inyo County | Habitat, Mohave Desert water tank, Riverside County © Guntram Deichsel |

Habitat, Granite Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon | Habitat, Santa Ana Mountains, Riverside County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult in brush pile habitat, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos of Great Basin Fence Lizards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A female fence lizard runs across a wall in Riverside County and encounters a male who pursues her. She rejects him and he runs to an open spot on top of the wall and does a push-up display. | A male fence lizard in Inyo County defensively showing his throat color and doing push-ups. | Large, dark phase Great Basin Fence Lizards bask and eat ants off rocks in Inyo County. |

Two male fence lizards fight over territory, biting on to each other's mouth. San Diego County © Stan Budz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos of Other Subspecies of Western Fence Lizard | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A male Northwestern Fence Lizard defecates off the side of a Butte County fence, wipes himself off, then does a territorial push-up display. | I'm not going out of my way trying to film this behavior - I can only take what I get - so here we see another Northwestern Fence Lizard doing his business for the camera. It's like they're trying to tell me something. | Two Coast Range Fence Lizards, Sceloporus occidentalis bocourtii, are observed during the breeding season in early May in San Benito County. The first lizard, a female, has moved from her perch on a rock to a nearby rock in order to get away from the photographer. She begins a territorial push-up display when a male comes up the side of the rock and begins to pursue her. She arches her back and hops away in order to reject him. She may have already mated and is bearing eggs, or maybe he is not her type. He finally stops and does a push-up display, possibly to continue trying to entice her, or possibly to warn the photographer that this is his territory. |

A male Northwestern Fence Lizard fights with a female in Placer County © Rod | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A few fence lizards in Contra Costa County. | A male fence lizard on a tree in Alameda County. | Several juvenile fence lizards come out to bask in the sun on a cool and windy morning in early March. | San Joaquin Fence Lizards on trees along a river in early spring. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sierra Fence lizards run around a rocky area in the woods 8,000 ft. high in the Sierra Nevada mountains. | A Sierra Fence Lizard, or intergrade, runs around rocks in the forest up at 5,600 ft. in Tuolumne County. | These two videos show a Placer County Northwestern Fence Lizard appearing to taunt a garter snake (a Mountain Gartersnake is my guess, because it lacks red.) The lizard keeps moving down towards the snake but when the snake moves towards the lizard, apparently trying to catch it for dinner, the lizard runs up the wall away from the snake. © Rod | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. This animal is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -