Common Chuckwalla - Sauromalus ater

Duméril, 1856Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Diego County | Adult male, San Diego County | Adult, Inyo County | Adult male, San Diego County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, wedged into a crack, Inyo County. The dark body matches its dark lava rock habitat. | Shedding adult female, San Diego County |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Diego County | Adult male, San Diego County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Diego County | Adult, Inyo County | Dark adult male on top of tall lava outcrop, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Diego County | Adult male, San Diego County | Adult, Antelope Valley, Los Angeles County © Todd Battey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male from lava fields in San Bernardino County © Patrick Briggs | Adult male (top) with adult female (bottom) from lava fields in San Bernardino County © Patrick Briggs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Riverside County © Chad Lane |

Adult, San Bernardino County © Loren Prins |

Adult male, San Diego County | Adult male, San Diego County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pale adult from pale sandstone habitat, San Diego County © Stuart Young | Adult, San Bernardino County © John Worden |

Adult male, San Bernardino County © Adam Clause | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Diego County © Adam G. Clause |

Adult, emerging from rock crevice, San Bernardino County © 2005 Joshua C. Pace |

Distant adult male in typical basking poisition, Imperial County | Adult female, Kern County © Ryan Sikola |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Inyo County | Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon | Adult, San Diego County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, San Bernardino County © Mike Ryan |

Adult male, San Bernardino County © Mike Ryan |

Adult in rock crack, San Bernardino County © Mike Ryan | Adult, Inyo County © Yuval Helfman |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distant adult female, Inyo County | Adult male, Riverside County © Jorah Wyer |

Large adult male, San Bernardino County. Note the large femoral pores. © Andrew Borcher The Common Chuckwalla is the second largest lizard native to the United States (after the Gila Monster). |

Adult female, San Bernardino County © Alexandra Hicks |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female, Clark County Nevada, © Brian Hubbs |

Adult, San Bernardino County © Terry Goyan |

Dark adult from lava flow, San Bernardino County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Hypomelanistic adult, Riverside County © Brody Trent |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mating adults, San Bernardino County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg | Adult male from dark lava habitat in San Bernardino County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Adult feeding on top of a bush in San Bernardino County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult emerging from crevice to bask, San Diego County |

Adult, eyeballing the photographer, Inyo County © Jaye B. |

Chuckwallas have a back that is covered with granular scales. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Juveniles |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Riverside County © Chad Lane |

Juvenile, Riverside County © Jeremiah Easter |

Hatchling from dark volcanic rock habitat, Imperial County © Stuart Young | Juvenile, San Bernardino County © Ryan Martin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile from mud hills in San Diego County © Douglas S. Brown | Juvenile in April, San Bernardino County © Lady Li Andre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile in dark lava rock habitat, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mid-sized juvenile next to a crack it uses for shelter, San Bernardino County © Mike Ryan |

Juvenile, San Bernardino County |

Hatchling without yellow coloring, Riverside County © Adam G. Clause | Juvenile, Kern County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chuckwallas in Native American Culture | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

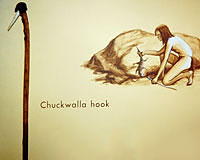

| A Chuckwalla hook on display at the Death Valley National Park Visitor Center. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| When threatened, a Chuckwalla typically escapes into a rock crevice. If a predator attempts to pull it out, the lizard will use its rough skin and strong claws to wedge itself tightly into the crevice, sometimes inflating with air to further increase its pressure against the rock. The tool shown above - a sharpened stone attached to a stick - was used by Native Americans to pull a Chuckwalla from a crevice. The sharp angled stone impaled the lizard forcing it to release its pressure against the rock allowing it to be pulled out of the crevice. The Chuckwalla was later cooked and eaten or possibly dried and smoked to preserve the meat for later use. See below for more information about how Chuckwallas were prepared and eaten. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Todd Battey took these pictures in the Coso Range in southern Inyo County, an area known for its extensive Native American pictographs by the Piute tribe. The large rock contains paintings of deer and bighorn sheep on one side, and human-like forms on the other, including what looks to be a large lizard (the painting is 1.5 feet long) which is certainly a Chuckwalla, considering the importance of this large lizard to these desert inhabitants. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Diego County | Habitat, Imperial County | Habitat, San Diego County | Volcanic rock habitat, Inyo County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Bernardino County, with a distant Chuckwalla sitting on top of the rock pile in the center of the picture. | Habitat, Riverside County | Artificial riprap habitat, Imperial County | Habitat, Owens Valley, Inyo County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Volcanic rock habitat, Imperial County © Stuart Young |

Sandstone habitat, San Diego County | Habitat, Inyo County | Habitat, Imperial County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mud hills habitat, San Diego County desert © Douglas S. Brown | Habitat, Imperial County | Habitat, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Diego County | Habitat, San Diego County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A large old male chuckwalla gets some sun, does some pushups, eats some bushes, then poops. | A Chuckwalla emerges from its crevice and does a territorial push-up display. | From a wide view of its habitat, we zoom in on a Chuckwalla high on top of a rock. | Chuckwallas in the San Diego County desert, including one that crawled up into a bush to eat some flowers. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Riverside County chuckwalla runs across a sandy wash into thick vegetation next to a spring and a San Diego County chuckwalla displays on top of a large rock outcrop. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are more pictures of this species and its habitat on our Southwest and Baja California pages. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. This common species is on the Special Animals List for some mysterious reason. There are no indications from the list that it is threatened in any way. In 2007, this lizard was legally collectable with a license. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -