|

This species has been introduced into California. It is not a native species.

|

|

| Adult, Inyo County © 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

|

|

|

Adult, Inyo County

© 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

Adult, Inyo County

© 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

Adult, Inyo County

© 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

|

|

|

Adult, Inyo County

© 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

Adult, Inyo County

© 2021 Elliot Jaramillo |

Adult, Las Vegas, Nevada

© William Flaxington |

|

|

|

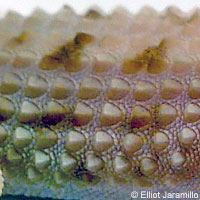

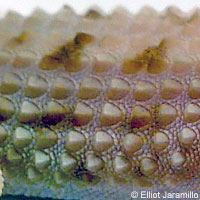

The tail and body are covered with large keeled scales.

Compare with the smoother tail of the Mediterranean Gecko. |

Toes are thin and clawed, without expanded tips or pads underneath.

Compare with the padded toes of the Mediterranean Gecko. |

| |

|

|

|

Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 3 to 4 and 5/8 inches long (7.5 - 11.7 cm) including the tail.

Maximum head and body size is 2 inches (5.1 cm).

Hatchlings are 1 and 5/8 to 2 and 3/8 inches long including the tail (4.1 - 6 cm).

(Powell, Conant, & Collins 2016)

|

| Appearance |

A small lizard with a slender body covered with enlarged keeled scales.

The tail is covered with enlarged keeled scales.

Toes are long and thin, barely wider than the toes, with claws but no toe pads.

Eyes with vertical pupils. Lacks eyelids. Eyes are covered with transparent scales.

Color is a sandy beige with dark brown spots that form a fairly regular dorsal pattern.

The belly is white.

The tail is marked with dark brown cross bands or spots.

(Powell, Conant, & Collins 2016)

|

| Life History and Behaviors |

A nocturnal wall climber at home around human habitations and often assosiated with hunting under electric lights at night.

Given their native desert habitat, it's likely they can survive in rocky desert areas without much water.

|

| Diet |

| Eats a variety of invertebrates, probably including flying insects. |

| Reproduction and Young |

This species is comprised of males and females and reproduction is sexual.

In its native habitat in Qatar, females are known to lay clutches of one or two eggs several times a year from about April to October. Communal egg-laying sites have been observed. (Qatar e-Nature)

In Galveston Texas, hatchlings, juveniles, and adults were all evident in mid-September, which corresponds to the April to October egg-laying observations. (NatureServe Explorer citing Bloom et al. 1986)

|

| Habitat |

Found in natural and altered landscapes.

Favors dry rocky desert areas in its native habitat, and is also commonly found in and around human structures.

A

common house gecko in cities and towns in its native habitat.

Habitat in Texas is the upper walls of dockside buildings (inside and out.) (Bartlett and Bartlett 1999).

First documented habitat in California is at a developed riparian area in the Mojave Desert 210 feet (64 m) below sea level.

|

| Range |

Native Range

From the edge of eastern Egypt south along the Red Sea to Eritrea, and east to Syria, Jordan, southern Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and along the shore of the Persian Gulf through Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the U.A.E. and Oman. Also in a few isolated areas in Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in the U.S.A.

Introduced in Galveston, Texas since at least since 1983. As of 12/21 this species has also been found in Yuma and the greater Phoenix area in Arizona, in the greater Las Vegas area of Nevada, and in California. It is expected to spread further through the desert southwest and possibly farther.

You can view a map of the observations posted on iNaturalist.

Distribution in California

The species was first reported in California October 8th, 2019 at Fort Irwin in San Bernardino County, where it was probably a stowaway on a military airplane returning from the Middle East: iNaturalist observation by Chris Preston. The observation was not vouchered. It is not known if there is an established population there.

A vouchered record of the species in California was first documented in December 2021.

(Hansen & Nafis, Herpetological Review 52(4), 2021)

Elliot Jaramillo contacted this website for an identification of a gecko he found in an underground electric box January 22, 2021 at Furnace Creek, Death Valley National Park, in inyo County. One gecko was vouchered, and another gecko was also observed at the location.

Jaramillo pointed out that food and supplies are brought to the location on a regular basis from Las Vegas, where the species has become established. This is likely how the geckos were transported to the location. There is a small airport at the location which could be another source of the lizard introductions. There are also several campgrounds and a visitor center, which all make for a lot of tourist traffic at the location. This traffic is a less-likely source of the introduction of the species, but it's possible that outgoing vehicles could contribute to the continuing spread of the species to other locations.

"The relatively rapid expansion, apparently via movement of equipment and materials (Babb 2014. Herpetol. Rev. 45:461-462), and its ability to occupy both native and altered landscapes suggest the potential to eventually colonize much of the Mojave Desert. The observations of multiple individuals at the Death Valley site suggests an established population."

(Robert W. Hansen, Herpetological Review 52(4), 2021)

|

|

| Red dots: Some areas where this species has apparently been established in the U.S.A. |

|

Red areas: Native Range

|

| Taxonomic Notes |

Cyrtodactylus basoglui is a junior synonym of Cyrtopodion scabrum.

Some other synonyms include:

Tenuidactylus scaber — SINDACO 1995

Cyrtopodion scaber — RÖSLER 2000

(See more at The Reptile Database)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

It is not yet known what effect introduced populations of this lizard might have on native wildlife.

In Galveston Texas, where the gecko has been seen since 1983, it appears to have displaced the Mediterranean Gecko which was formerly found there.

(NatureServe Explorer citing Klawinski et al. 1994)

It's possible this might happen in California also. |

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Gekkonidae |

Geckos |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Cyrtopodion |

? Cyrtopodion |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

Species

|

Cyrtopodion scabrum |

Rough-tailed Bowfoot Gecko |

(Heyden, 1827) |

|

Cyrtopodion - Fitzinger, 1843

Cyrtopodion scabrum - (Heyden, 1827)

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name

|

Cyrtopodion:

Greek - kyrto = curved

Greek -

podion = foot

Scabrum:

Latin = physically rough or scabrous - covered with scales.

|

|

Keeled Rock Gecko

Bow-footed Gecko

Rough-tailed Gecko

Rough Bent-toed Gecko

Rough-tailed Bowfoot Gecko

Common Tuberculate Ground Gecko,

Keeled Gecko

|

Related or Similar California Lizards

|

Peninsular Leaf-toed Gecko - Phyllodactylus nocticolus

Non-native geckos in California

Rough-tailed Gecko - Cyrtopodion scabrum

Common House Gecko - Hemidactylus frenatus

Indo-Pacific Gecko - Hemidactylus garnotii

Tropical House Gecko - Hemidactylus mabouia

Flat-tailed House Gecko - Hemidactylus platyurus

Mediterranean Gecko - Hemidactylus turcicus

Yellow Fan-Fingered Gecko - Ptyodactylus hasselquistii

Ringed Wall Gecko - Tarentola annularis

Moorish Gecko - Tarentola mauritanica

|

More Information and References

|

The Reptile Database

Wikipedia

NatureServe Explorer

Qatar e-Nature

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Dixon, J. R. Amphibians and reptiles of Texas. Second edition. Texas A & M University Press, College Station, 2000.

Bartlett, R. D. & Bartlett, P. A Field Guide to Texas Reptiles and Amphibians. Gulf Publishing Co., Houston, Texas, 1999.

Robert W. Hansen & Gary Nafis. Herpetological Review 52(4), 2021

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G5 |

Secure |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

LC |

Least Concern |

|

|

|

Red Dots: Areas where this non-native species has been observed and could be established

Red Dots: Areas where this non-native species has been observed and could be established