|

This species has been introduced into California. It is not a native species.

|

|

|

| Sub-adult, Orange County © Lester Townsend |

|

|

|

Adult, Orange County

© William Flaxington |

Juvenile, Orange County

© William Flaxington |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

|

|

|

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

|

|

|

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

|

|

|

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

Adult, Orange County

© Ryan Winkleman |

|

|

|

| Adult, Orange County © Larry Leon |

| |

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

| This small juvenile found in Orange County is thought to be a juvenile alien whiptail and not a native Belding's Orange-throated Whiptail due to the fact that its tail is not blue, but I could be wrong. Belding's juveniles of this size should have a blue tail.They lose the blue color as they age, but I don't know at exactly what size they lose it. © Kevin Lentz |

Juvenile, Orange County

© William Flaxington |

| |

|

|

| Sonoran Spotted Whiptails From Their Native Range |

| |

|

|

|

| Cochise County, Arizona |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

|

|

|

| Santa Cruz County, Arizona |

Adult, Pajarito Mountains,

Santa Cruz County, Arizona |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

| |

|

|

| Native Habitat |

|

|

|

| Cochise County, Arizona |

Pajarito Mountains, Santa Cruz County, Arizona

|

Santa Rita Mountains,

Santa Cruz County, Arizona

|

| |

|

|

| Short Videos of Whiptails in Their Native Habitat |

|

|

|

An adult Sonoran Spotted Whiptail crawls along the ground in the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona.

|

Sonoran Spotted Whiptails in

Santa Cruz County, Arizona. |

|

| |

|

|

| Description |

All life history and behavioral information is based on the two species as observed in their natural habitat.

|

| Size |

The average snout to vent length is approximately 3.5 inches (9 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A moderately-large slim-bodied lizard with a long slender tail, a pointed snout, large symmetrical head plates, and a long tail tapering to a thin point about twice the size of the body.

|

| Color and Pattern |

This information is based on previous descriptions of two species which were merged into one - Aspidoscelis flagellicauda and Aspidoscelis sonorae.

The ground color is blackish, brown, or reddish.

There are 6 distinct light-colored longitudinal stripes on the back and sides.

Light spots are present in the dark fields between the stripes. Spots that are lighter in color than the light stripes may also extend onto the stripes. Older individuals tend to be more heavily spotted.

The underside is cream colored and not marked.

|

| Young |

Juveniles are similar to adults but have few spots and the contrast between the light stripes and the dark fields is greater.

|

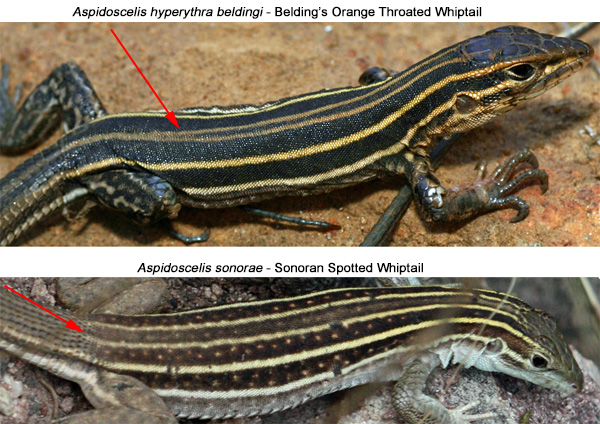

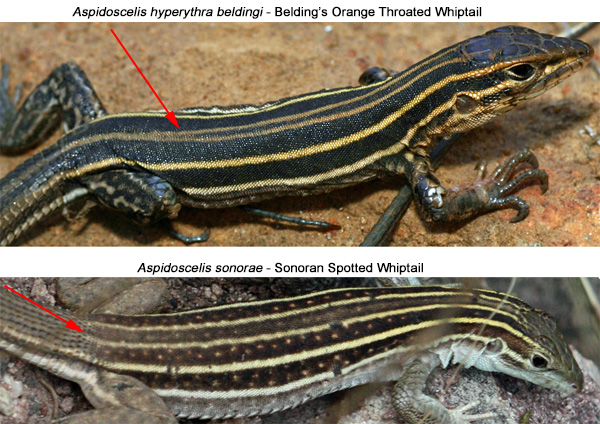

| Comparison With Similar Species |

Similar in appearance to the native species Aspidoscelis hyperythra beldingi - Belding's Orange-throated Whiptail

To differentiate them note the paravertebral stripes (the two stripes on either side of the middle of the back) as illustrated below.

The paravertebral stripes on A. sonarae remain parallel and fade out on the tail.

The paravertebral stripes on A. h. beldingi merge together and become a single mid-dorsal stripe that extends onto the tail.

|

|

| Life History and Behaviors |

Activity |

Active on sunny days in the morning and afternoon, becoming inactive on very hot days or cloudy days.

Both species are active from about April through October or November. Most active between May and August.

Moves actively and rarely appears to stop, though they will rest in the shade occasionally.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats a variety of insects (termites, beetles, grasshoppers) arthropods, and spiders

A very active forager, often continually moving along the ground, poking its snout into leaf litter and bushes, and sometimes using the feet to dig into and scratch leaf litter when searching for food.

|

| Reproduction and Young |

All members of this species are females that do not need males to fertilize their eggs. They reproduce with unfertilized eggs. The eggs hatch into genetically identical female lizards.

A. sonorae lays 2 or 3 clutches of 1 - 7 eggs, with an average of 4, from June through August which hatch about 2 months later.

|

| Habitat |

In California, found in landscaping and on parking lot asphalt. Described by Winkleman and Backlin as "...strongly acclimated to the urbanized environment and readily using spaces underneath concrete slabs for shelter."

Native Habitat

Found in oak and pine and pinyon/juniper evergreen woodlands, interior chaparral, sometimes in semi-desert grasslands, desert scrub, and seems to prefer riparian corridors.

|

| Geographical Range |

Range In California

Established in Orange County.

Discovered in Irvine, they have also been found in surrounding communities where they continue to spread.

Also reported from:

San Diego County in Oceanside.

Los Angeles County in the city of Los Angeles, where they could also be established.

Sacramento County - northeast of Sacramento. iNaturalist reports show at least one juvenile so they are apparently established.

Native Range (Shown on map below)

Ranges across central and southeast Arizona into New Mexico with an isolated population in the Chiricahua and Catalina Mountains of Arizona, and south into the northern parts of the states of Chihuahua and Sonora in Mexico.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Original Discovery in California

In April 2015 a population of alien whiptails observed in Irvine in May 2014 was reported on iNaturalist.org.

Ryan S. Winkleman & Adam R. Backlin published a note in June 2016 * documenting non-native whiptails they found in Irvine. Experts could not identify the exact species and called them "Aspidoscelis flagellicauda/sonorae complex (Spotted Whiptail)."

"Presumably introduced as a single released/escaped pet that subsequently underwent asexual reproduction and established a small, localized population." * These whiptails are all females that reproduce with unfertilized eggs, which allows them to colonize and spread quickly from just one female. Both adults and juveniles were observed, showing that they have established a population. Although the authors concluded that the whiptails were apparently extirpated from the original observation site, Ryan Winkleman informed me that after the note was published several whiptails were observed there, indicating that they are still extant there. I have also received a personal communication from a biologist who observed a few whiptails in June 2016 while conducting a bird survey about two miles from the originally documented area.

The authors also mention that at least one similar whiptail was observed in the neighboring city of Lake Forest, suggesting that the whiptails are more widespread in the region and possibly expanding their range. (I have received other reports that they are well-established there now.)

According to Winkleman and Backlin "The Aspidoscelis flagellicauda/sonorae complex are triploid unisexuals which makes it difficult, if not impossible, to identify these lizards to the species level with just mtDNA. To complicate the identification further, many of the morphological characters that are used to differentiate A. flagellicauda from A. sonorae, including pre-anal scale counts, number of granules between the paravertebrals, and the number of scales around mid-body, were not useful in narrowing the identification. The collected specimens, as examined by Greg B. Pauly, were found in each case to have one character that would favor identification as one species and another contradictory character that would favor identification as the other species. For the purpose of this note, because the specimens are non-native and apparently extirpated from the collection site, [it was later shown that they are not extirpated from the site] we feel that identification to species is not significant and may not be possible without nuclear sequence data due to the aforementioned circumstances."

[Ryan S. Winkleman & Adam R. Backlin, Herpetological Review 47(2), 2016)]

In 2022 Samuel Fisher et al published a paper describing another population found in Oceanside, San Diego County.

|

This map shows where the species occurs naturally, not where it has been introduced in California.

|

| Native Elevational Range |

Found primarily between 700 and 7000 feet elevation (215 to 2130 meters).

|

| Taxonomic Notes |

Name Change

Taylor et al (2018) relegated A. flagellicaudus (Lowe and Wright 1964) to the synonymy of A. sonorae (Lowe and Wright 1964). Their study found that the formal descriptions of Aspidoscelis flagellicaudus and Aspidoscilis sonorae were extremely brief and confirmation that they were two legitimate natural species is lacking. They found that color pattern, preanal scale arrangements and other traditional methods for differentiating the two species are not effective and concluded that the two species are different pattern classes of one species, Aspidoscelis sonorae.

(Harry L. Taylor, Charles J. Cole, Carol R. Townsend. Relegation of Aspidoscelis flagellicaudus to the Synonymy of the Parthenogenetic Teiid Lizard A. sonorae Based on Morphological Evidence and a Review of Relevant Genetic Data. Herpetological Review 49(4), 2018 )

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| These newly-introduced non-native whiptails could possibly impact the native Orange-throated Whiptail and other native lizards and possibly other insectivores in competition for food and territory. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Teiidae |

Whiptails and Racerunners |

Gray, 1827 |

| Genus |

Aspidoscelis (formerly Cnemidophorus) |

Whiptails |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

A. sonorae |

Sonoran Spotted Whiptail |

(Lowe and Wright, 1964) |

| |

|

|

|

|

Original Description |

Aspidoscelis T.W. Reeder et al. 2002

Cnemidophorus sonorae Lowe and Wright, 1964 - Journ. Arizona Acad. Sci., Vol. 3, p. 80

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name

|

Aspidoscelis - Greek - aspido = shield + skelos = leg

Sonorae = of the Sonoran Desert — references the region of occurrence.

Taken in part from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Alternate Names

|

The lizards introduced into California were originally identified as

hybrids of two whiptail species - Aspidoscelis flagellicaudus - Gila Spotted Whiptail and Aspidoscelis sonorae - Sonoran Spotted Whiptail.

|

|

Related or Similar California Herps

|

A. t. stejnegeri - Coastal Whiptail

A. t. munda - California Whiptail

A. t. tigris - Great Basin Whiptail

|

|

More Information and References

|

Herpetological Review47(2), 2016

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Fisher S, Fisher RN and Pauly GB (2022) Hidden in Plain Sight: Detecting Invasive Species When They Are Morphologically Similar to Native Species. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:846431. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.846431

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

Taylor, Emily. California Lizards and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2025.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

None |

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

None |

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

None |

|

|

|

Red: Range in California where this

Red: Range in California where this