|

This species has been introduced into California. It is not a native species.

|

It is unlawful to import, transport, or possess this species of frog in California

except under permit issued by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

(California Code of Regulations, Title 14, Excerpts, Section 671) |

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife Coqui page requests you take this action if you find [or hear] a Common Coquí:

"If you observe this species in California, please report your sighting to the CDFW Invasive Species Program, by email to Invasives@wildlife.ca.gov, or by calling (866) 440-9530."

|

|

|

|

Adult, Hawaii, Hawaii

© William Flaxington |

Adult, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture |

|

| |

|

|

| Links to More Pictures and Video |

YouTube Video of Calling Male |

University of Hawaii at Manoa

(Pictures of Eggs)

|

Common Coqui

Invasive Species Fact Sheet -

California Department of

Fish and Wildlife

|

|

|

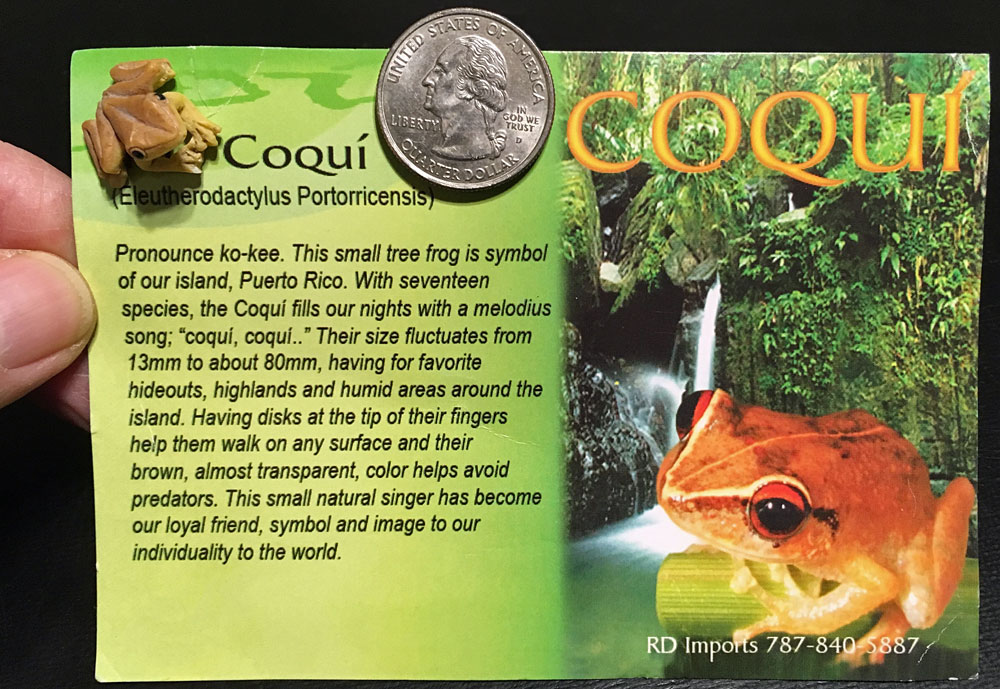

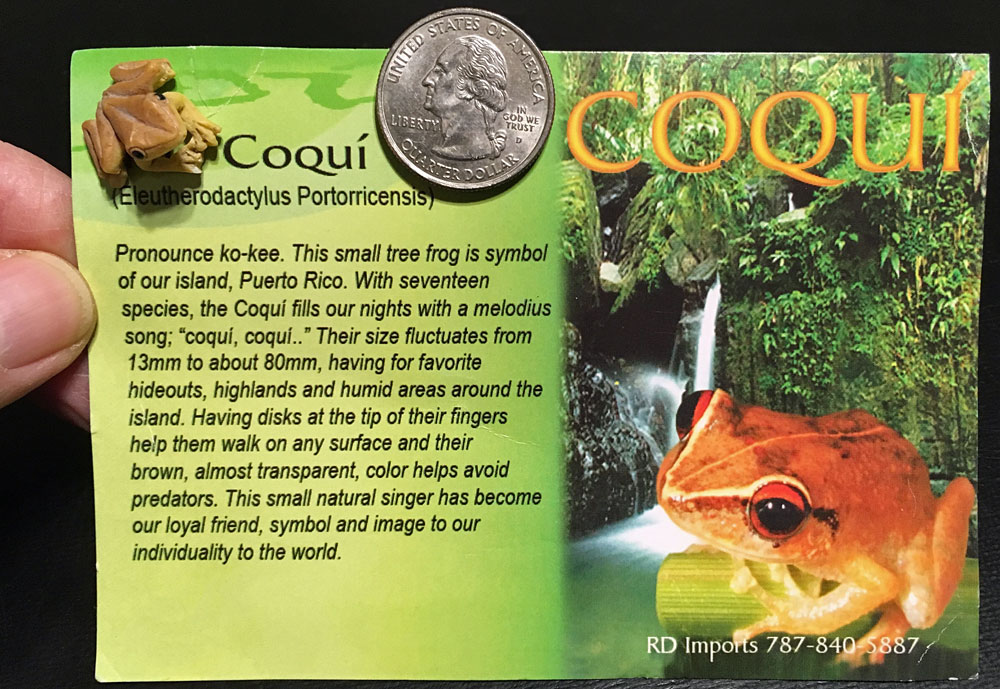

| The Common coquî is considered an unwanted invasive species in Hawaii and California and elsewhere, largely because of the loud call the males make, which changes the sound of an environment considerably. However, the frog and its call are a proud symbol of its native island of Puerto Rico, as you can read on this post card that I was sent by friends. The card came with a life-sized plastic frog attached to the corner. (I put a U.S. quarter dollar coin next to it for size comparison. |

| |

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

A very small frog. Adults are roughly the size of a US quarter dollar coin.

Adult males average 34 mm measured snout to vent (1.3 inches) with a range of 30 - 37 cm (1.2 - 1.5 inches.)

Adult females average 41 mm measured snout to vent (1.6 inches ) with a range of 36 to 52 mm (1.4 - 2 inches.)

Hatchlings are only about 5 mm in size! (1/2 inch.)

|

| Appearance |

A small plain frog without webbing between the toes.

Toe pads are enlarged to facilitate climbing.

Color and pattern are variable:

Frogs can be gray, gray-brown, rich brown, or tan in color.

The dorsal pattern is highly-variable and can be obscure or prominent consisting of brown marks and black spots. Sometimes a light dorsolateral stripe is present.

The venter is white or pale yellow in color often with small brown spots.

The male vocal sac is large and rounded.

|

| Life History and Behaviors |

Common Coquí are nocturnal.

During daylight they hide in rock piles or under leaves or other ground debris.

Sometimes

active during overcast or rainy days.

Common Coquí are not adapted for swimming. Feet lack webbing and toe pads are enlarged to facilitate climbing.

Sit-and-wait predators: frogs feed by sitting and waiting

for prey to come close enough for the frog to jump and grab it with their mouth.

|

| Voice (Listen) |

At night males produce a loud two-part high-pitched call that sounds like the frog's name "ko-kee" with the accent on the "kee."

Male and female Common Coquí respond to different nots of the call

The "co" part of the sound repels other males and establishes territory.

The "kee" part of the sound attracts females.

Males call from a perch above ground.

(Calling does not need to occur in or beside a body of water.)

"...females produce soft, rasping vocalizations to defend their feeding sites." (Amphibiaweb citing Stewart and Rand, 1991) |

| Diet |

Eats invertebrates, primarily arthropods. Diet includes spiders, moths, crickets, snails, small frogs, and sometimes eggs. Males sometimes eat eggs from their own clutch.

Juveniles eat smaller prey such as ants |

Territoriality

|

| Males challenge each other for territory with their calls and the frog that first falters in a singing duel leaves the area without any violent physical contact. |

| Longevity |

| Adults may live as long as 4 - 6 years. |

| Reproduction |

In their native Puerto Rico, Common Coquí breed year round.

In California and other locations of introduction, breeding is probably more common during periods of high heat and high humidity.

Frogs become adults ready to reproduce when they are about 8 months old.

Breeding is not dependent on water, which makes it easier for this alien frog to spread since breeding is not confined to ponds or rain pools.

|

| Eggs |

Eggs when laid are approx. 3 mm in size. (See some pictures here.)

Puerto Rican females lay about 34-75 eggs 4 to 6 times per year. Frogs in Hawaii have been found to lay about 26 clutches per year - or more than 1,400 eggs per female per year!

Eggs are laid on land - on leaves of terrestrial plants and sometimes abandoned bird nests.

"The one to two dozen eggs are laid in moisture-retaining pockets amid ground debris or, occasionally, in protected, elevated sites. Males tend the clutches from deposition until shortly after hatching." (Bartlett and Bartlett)

Eggs hatch in 17 - 26 days (or 14 - 17 days?).

|

| Larvae and Young |

Common Coquí larvae undergo direct development - there is no tadpole stage.

Juveniles hatch out of the eggs as fully-formed frogs with a short tail that is lost shortly after hatching.

Hatchlings are aprox. 5 mm in size (1/2 inch.)

|

| Habitat |

Occurs in a wide range of habitats in its native Puerto Rico, including broadleaf forests, mountains, and in urban vegetation.

Frogs can be terrestrial and arboreal, often climbing into the canopy.

So far in California the frogs appear to be very localized and dependent on sprinkler irrigation systems to receive adequate moisture.

|

| Range |

Non-Native Range

The presence of this invasive species still tenuous in California. It may not actually be established. I have added it to my state list in order to help educate people about its presence, hoping that this will help to prevent it from spreading and becoming established in the state.

The Coqui is listed as established in several locations in Southern California, but there is not much information about where those locations are. The presence of this alien frog is more apparent than that of most invasive species because their loud nocturnal calls are conspicuous and unfamiliar and annoying. It has been found in a number of locations in southern California, including private residences and nurseries in Orange County, Beverly Hills, and Ocean Beach, but it was apparently not established in all of those locations and may not be present anymore.

When I last checked the USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species database in October, 2023, the Common Coqui was listed as being found in four locations:

- A wholesale plant nursery in Torrance, L.A. County, in 2015

- A private residence in Orange County in 2012

- A greenhouse in San Diego County in 2012

- Ocean Beach, San Diego County in 2014.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife included the Common coqui on their list of invasive species in California.

(It's possible there have been more sightings after it was written.)

Common Coqui Invasive Species Fact Sheet

"Current Distribution

A single coqui was collected from a private residence in Orange County in 2012 and was determined to have originated by “hitchhiking” on a tropical house plant. Subsequent inspections of the nursery from which the plant was purchased, in San Diego County, detected (heard) multiple calling males and resulted in the collection of one adult, two froglets, and a cluster of coqui eggs. Currently, that population appears to be confined to the single nursery site. However, in 2014, after a month of nightly calling, what homeowners in Ocean Beach (San Diego) thought to be a songbird was determined to be a coqui."

Native Range

The species is native to the island of Puerto Rico.

Introduced to the Puerto Rican islands Isla Vieques and Isla Culebra, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Florida, and Hawaii. Individuals have also been found transported to other locations, including NewOrleans and Boston, but was never established. (Amphibiaweb)

Established in Florida since at least the 80s but it is still localized and restricted mostly to greenhouses in southern Dade county.

Introduced into Hawaii in the late 1980s and is now a densely populated invasive species that has been found to be established on the islands of Hawaii, Oahu, Maui, and Kauai. At least one established population was completely eradicated on Kauai, and attempts are still being made to get rid of frogs throughout the state.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Found at sea level to 1,200 m (3,900 ft.) in elevation in Puerto Rico.

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

An invasive species. The main concern about the establishment and spread of this species is the hight volume of noise that males produce when they call at night, but it seems apparent that if these frogs were to become widespread they would compete for invertebrate prey with many native species of reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds.

This frog was included on the 2014 Global Invasive Species Database list of the 100 worst invasive alien species.

Looking at the history of the introduction of Common Coquí in Florida, it is doubtful that frogs established in California will be able to disperse naturally around the state, since they are heavily dependent on warm and wet conditions. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Common Coquí were introduced several times in southern Florida but not established until 1973 at a Tropical Garden in South Miami. That population was extirpated by a severe freeze in 1977. Another population was established at a Homestead nursery in 1976 that imported bromeliads from Puerto Rico and populations still occur at several nurseries in the Homestead area. Frogs cannot disperse naturally from these nurseries as they are susceptible to droughts and freezes, and they might not even be self-sustaining, being dependent on new arrivals in plant shipments from Puerto Rico.

Article about Common Coquí in Hawaii - LA Times 12/27/14

The density of Common Coquí in Hawaii is apparently 3 times greater than it is in the frog's native Puerto Rico and females have been found to lay more than four times as many eggs per year as they do in Puerto Rico.

In it's native Puerto Rico, the species is stable in the lowlands but declining in the uplands due to habitat loss, primarily from clearing land for agriculture, disease (chytridiomycosis), and probably from introduced predators such as rats and mongooses. (Amphibiaweb)

|

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Leptodactylidae |

Southern Frogs |

| Genus |

Eleutherodactylus |

Rain Frogs |

Species

|

coqui |

Common Coquí |

|

Original Description |

Thomas, R. (1966). "New species of antillean Eleutherodactylus". Quart. J. Florida Acad. Sci. 28: 375–391.

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name

|

Eleutherodactylus - Greek = free toes (refers to the lack of webbing between the toes often found in other frog species)

coqui - refers to the two-part sound made by male frogs that sounds like "ko - kee."

|

|

Alternate Names

|

Coquí

Puerto Rican Coquí

|

|

Related or Similar California Herps

|

The Common coquí is unlike any other native California frog, but it is similar to some species available at pet stores which might be found as feral individuals in the wild in California.

|

|

More Information and References

|

California Department of Fish and Wildlife Invasive Species

Wikipedia - Common coquí

University of Hawaii at Manoa

National Wildlife Federation

Maui Sierra Club

Amphibiaweb

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Conant, Roger, and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians Eastern and Central North America.

Third Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.

R. D. Bartlett and Patricia P. Bartlett. A Field Guide to Florida Reptiles and Amphibians. Gulf Publishing Company, 1999.

Walter Meshaka, Jr., Brian P. Butterfield, J. Brian Hauge. The Exotic Amphibians and Reptiles of Florida. Krieger Publishing Company, 2004

|

| |

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This frog is not native to California. It is recognized as an invasive species by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

| USDA Forest Service |

|

|

| IUCN |

Upland populations on Puerto Rico should be labeled as "near threatened." |

|

|

|