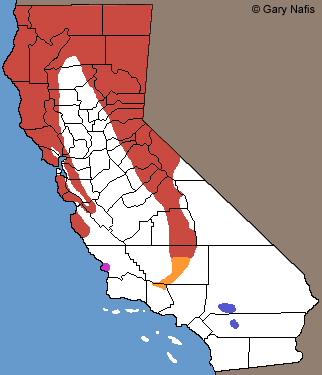

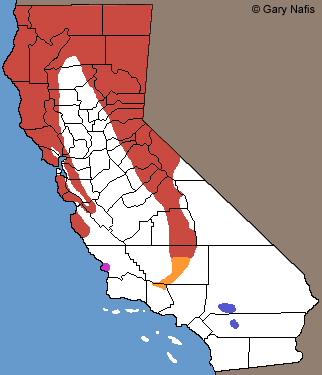

Red: Range of this species in California

Charina bottae - Northern Rubber Boa

Dark Blue: Range of similar species

Charina umbratica - Southern Rubber boa

Orange: area where the species of rubber boa

is recognized as potentially Charina umbratica by the CDFW.

Purple: Area representing recently-discovered

boas of unexamined species, most likely Charina bottae.

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

|

|

| Adult, Alpine County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Napa County |

Adult, Napa County (in situ, stretched out on log bottom left) |

Adult, Santa Cruz County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, 8,000 ft. elevation, Alpine County |

Adult, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

|

|

|

|

| Large, old, scarred adult, Marin County |

Adults, Marin County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Marin County |

Dark adult, Marin County

© Luke Talltree |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Contra Costa County |

Dark adult, Marin County © Natalie McNear |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Santa Cruz County

(Specimen courtesy of Mitch Mulks) |

Adult, El Dorado County, with colorful eyes. © Richard Porter |

Underside of adult, Marin County |

Adult, ready to shed, Marin County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with unusual black eyes, San Mateo County © Natalie McNear |

Adult with unusual black eyes, San Mateo County © Chad M. Lane |

Adult, Santa Cruz County © Zach Lim |

Adult, Sierra County.

© 2005 Jackson Shedd,

Specimen courtesy of John Stephenson

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mendocino County |

Adult, Fresno County © Paul Maier |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Fresno County

© Patrick Briggs

|

Adult, Mono County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Butte County © Jackson Shedd |

Adult, Alameda County © Ben Witzke |

|

|

|

|

| When threatened, Rubber Boas will often roll into a ball, hide their head and elevate the tip of their tail to fool a predator into attacking the tail which looks somewhat like a head. The tail is less-vulnerable than the head and can withstand attacks without much damage. Some boas have many scars on the tail from this tactic. You can see this behavior in the video below. |

Adult found at 7,825 feet elevation in Inyo County. © Jason Fitzgibbon |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with unusual dark markings, Santa Cruz County © Jared Heald |

Old adult with dark markings, El Dorado County © Richard Porter |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Nevada County © Julia Ggem |

Adult, 6,000 ft. elevation,

Tuolumne County © Jeffrey Harker |

Very pale adult, Santa Cruz County © Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Santa Lucia Mountains, Monterey County © Benjamin German |

Adult, San Mateo County a few miles south of San Francisco © Zach Lim |

Adult, Santa Clara County Mountains

© Parsa Fard |

Adult, Santa Clara County Mountains

© Parsa Fard |

|

|

|

|

Adult, San Mateo County

© Zachary Lim |

Group of adults, Marin County

© Chad Lane

In winter, it is not uncommon for several snakes, including multiple species, to share the same shelter. 8 boas were found under the same board along with a few Coast Gartersnakes. |

Rubber Boa skeleton, showing how the backbone is enlarged at the tail tip.

National Museum of Natural History |

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

Neonate, Butte County

© Jackson Shedd |

Juvenile, Madera County

© Patrick Briggs |

Juvenile, El Dorado County

© Jared Heald |

Juvenile, Butte County

© Rodney Lacey |

|

|

|

|

Juvenile from a dwarf population in

Kern County © Ryan Sikola |

Juvenile, Contra Costa County |

Juvenile from 7,200 ft. in northern Inyo County © Keith Condon |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile from near Weed, Siskiyou County © Kevin Lathrop |

Juvenile, Marin County |

|

Sub-adult, San Mateo County |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, Fresno County © Paul Maier |

Juvenile, Kittitas County, Washington

|

|

|

|

|

| These little pink newborns were found in early Fall in Butte County. © Marcus Rehrman |

Adult and juvenile boas found together in close proximity in San Mateo County

© Faris K |

|

|

|

|

| Sub-adult, Santa Cruz County © Yuval Helfman |

Juvenile, San Mateo County just south of San Francisco © Zachary Lim |

Juvenile, Tuolumne County © Zach Lim |

|

|

|

|

Comparison of two small snakes found near each other in Tuolumne County

Left: juvenile Northern Rubber Boa

Right: Coral-bellied Ring-necked Snake

© Emile Bado |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, San Mateo County |

Habitat, Napa County |

Habitat, Tuolumne County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, 2,500 ft. Santa Cruz Mountains, Santa Clara County |

Habitat, 8,000 ft., Alpine County |

Habitat, Marin County |

Habitat, Santa Cruz County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, San Mateo County |

Habitat, lava bed caves at around 4,500 ft. elevation in the Great Basin desert of Siskiyou and Modoc counties. Rubber boas are sometimes seen crawling on rocks inside these caves, where the average temperature is reported as 55 degrees. |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Butte County © Rodney Lacey |

Habitat, Santa Cruz Mountains,

Santa Cruz County |

Habitat, Contra Costa County

|

Habitat, Santa Cruz Mountains

© Zachary Lim |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Santa Cruz County redwoods

© Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

More pictures of this snake and its natural habitat are available on our Northwest Herps page.

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

It was 55 degrees F.around 8 PM at about 8,000 ft. elevation on a mountain pass in Alpine County when I saw this rubber boa crossing the road. It eventually dropped down a huge tree stump to get away from me and curled up under some tree bark.

|

As you can see in this video, when they feel threatened, Northern Rubber Boas often curl into a ball with their head hidden in the middle and the tail on the outside, elevated like a head, which it resembles. When a predator attacks what it thinks is a head, it will only injure the tail, which is much less life threatening to the snake. Many rubber boas have scars on their tails from such attacks |

Natalie took Chad and myself to look under a board she found in Marin County that is used as a shelter by at least 8 rubber boas. When Chad lifts it, we see 7 boas and a Coast Gartersnake. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

Not Dangerous - This snake does not have venom that can cause death or serious illness or injury in most humans.

Commonly described as "harmless" or "not poisonous" to indicate that its bite is not dangerous, but "not venomous" is more accurate. (A poisonous snake can hurt you if you eat it. A venomous snake can hurt you if it bites you.)

|

| Size |

Adults 14 - 33 inches in length (35 - 84 cm.) Typical size of adults is 15 - 25 inches. Newborns are 7.5 - 9 inches long.

Small or dwarf populations have been found in the Tehachapi, Greenhorn and Paiute Mountains, on Breckenridge Mountain, and on Mt. Pinos.

|

| Appearance |

A small constrictor with a stout body and a thick tail with a blunt end (that looks a bit like a head), and smooth shiny small-scaled loose and wrinkled skin, which gives the snake a rubbery look and feel.

Eyes are small with vertically elliptical pupils.

The top of the head is covered with large scales.

Males usually have anal spurs which are small or absent in females. |

| Color and Pattern |

Light brown, dark brown, pink, tan, or olive-green above, and yellow, orange, or cream colored below.

Usually uniform in color on the back, but sometimes dark spots or mottling occur, especially in northern populations, possibly due to scarring.

Usually no pattern below, but sometimes there is dark mottling. |

| Young |

Young snakes are pink or tan, and can be brightly-colored.

|

| Morphological Traits to Help Differentiate Charina bottae and Charina umbratica |

| |

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Nocturnal and crepuscular, sometimes active in daylight.

Sometimes active in weather that would be too cold for most reptiles, with surface temperatures in the 50s.

A good burrower, climber and swimmer.

Often found under logs, boards and other debris, sometimes on roads at dusk. |

| Defense |

The tail is short and blunt and looks like a head.

When threatened, the snake hides its head in its coiled body, and elevates the tail to fool an attacker into attacking the tail. Snakes with scarred tails are common. |

| Longevity |

| Known to live as long as 40 - 50 years in the wild. (Stebbins, 2003) |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Eats small mammals, birds, salamanders, lizards, snakes, and possibly frogs. |

| Reproduction |

Mating begins in spring soon after reemergence from winter brumation.

Females are viviparous, giving birth to an average litter of 1-5 young per year.

Females only reproduce on average once every four years.

Young are born some time from August to November.

|

| Habitat |

Grassland, mountain meadows, chaparral, woodland, along streamsides, deciduous and coniferous forest.

|

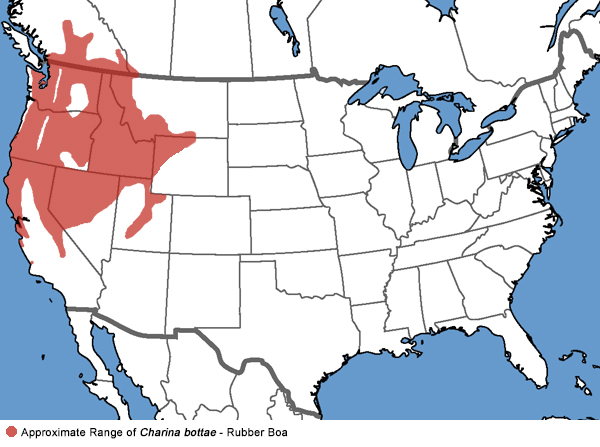

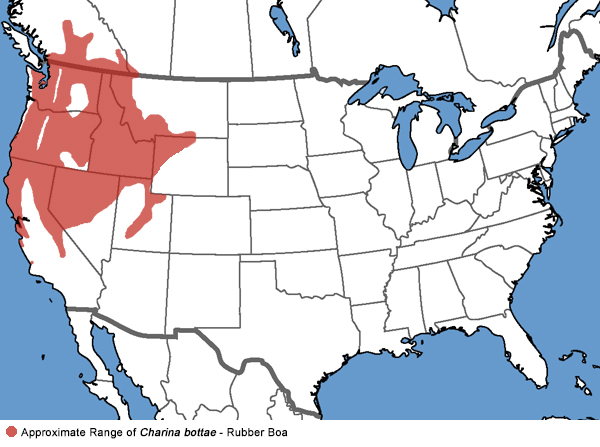

| Geographical Range |

Found from northern Monterey County north along the coast ranges into the Siskiyou Mountains and the northern Great Basin and south to the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains, including the east side to south of Mono Lake. Absent from the Great Valley and deserts.

Ranges out of California in Oregon, Washington, northwest Canada, Nevada, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming and Montana. (See map below.)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Since the species of Charina occurring in the southern Sierra Nevada, the Tehachapi Mountains, Mt. Pinos, and in San Luis Obispo County has not been determined, and because C. umbratica is a species protected by the state, I will show a separate area in purple on my range map of Charina that are of unknown species, and another in orange of Charina that appear to be classified as C. umbratica by the CDFW, until I learn of new scientific studies that change this.

1/15

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rubber boas were found in 2006 and 2010 at Montana de Oro on the coast of San Luis Obispo County, with photo confirmation in 2010. It seems most likely they would be C. bottae, but Stebbins & McGinnis (2012) state that C. umbratica occurs in the "northern part of the South Coast Range" which should include Montana de Oro, but until someone gets a permit to take a DNA sample from one of these snakes, which are found in a State Park, then finds another snake (which is not easy) and gets the sample tested, the species will remain unknown.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Description of the range of C. umbratica from Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012."C. umbratica is found in the northern part of the South Coast Range and at selected sites in Kern, San Bernardino, and Riverside Counties. These include Mount Pinos, Mount Abel, and the Tehachapi, San Bernardino, and San Jacinto mountains…."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife described the range of the Southern Rubber Boa (Charina umbratica) in a 2004 document (which has now been removed):

"The southern rubber boa is known from several localities in the San Bernardino Mountains in San Bernardino County, near Idyllwild in Riverside County, and on Mount Pinos in Kern County.

Recent genetic studies support separation of the southern rubber boa from all other populations of rubber boa. The subspecies appears to have diverged from the more widespread rubber boa between 12.3 and 4.4 million years ago. Possible intergrades between the southern rubber boa and the rubber boa found in the Tehachapi Mountains and on Mt. Pinos warrant further study."

No other CDFW documents that I can find as of 1/15

mention boas in the Tehachapi Mountains or in the Southern Sierra Nevada in their range descriptions. The most current fishing regulations protect all Kern County boas from take, but that could apply only to the Mt. Pinos Kern County population.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Richard Hoyer

has made extensive

studies of Charina. His position on the distribution of the Southern Rubber Boa (SRB) was explained to me in a personal communication:

"The only valid Scientific study that identifies the distribution of the SRB is the 1943 paper by L. Klauber in which he proposed adoption of the new SRB subspecies. That is, the SRB only occurs in the San Bernardino and San Jacinto Mts."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------MtDNA work has shown that most (but not all) Charina in the southern Sierra Nevada and the Tehachapis are more closely related to Charina bottae than to Charina umbratica. "Morphologically, the Kern Plateau, Breckenridge Mountain, Piute Mountains, Scodie Mountains, and Tehachapi Mts populations all are comprised of "dwarf-morph" snakes [similar to C. umbratica] but that trait does not track with the mtDNA." (R. Hansen Pers. Comm. 4/13) Because the morphology does not correspond to the mtDNA findings, there is not enough evidence to support an argument that these populations belong to either species. Until that evidence is found and published, I will continue to show the ranges of Charina in California according to the CDFW interpretation because C. umbratica is a protected species.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NatureServe Explorer Accessed 1/10/15.

Charina umbratica - Klauber, 1943 Southern Rubber Boa Distribution:

"Global Range: (1000-5000 square km (about 400-2000 square miles)) Range encompasses the San Bernardino Mountains and San Jacinto Mountains of southern California; populations in the Tehachapi Mountains and Mount Pinos area have some umbratica characteristics but are included in the C. bottae (northern rubber boa) clade (Rodriguez-Robles et al. 2001, Stebbins 2003). Elevational range is 1,540-2,460 meters (Stewart 1988). Twenty-six of the 40+ localities in the San Bernardino Mountains are in a 16-kilometer strip between Twin Peaks on the west and Green Valley on the east (Stewart 1988). Extent of occurrence is less than 5,000 square kilometers."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to over 10,000 ft. elevation (3,050 m). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Formerly, one species of Charina was recognized, Charina bottae, which was comprised of three subspecies:

C. b. bottae - Northern Rubber Boa,

C. b. umbratica - Southern Rubber Boa, and

C. b. utahensis - Rocky Mountain Rubber Boa.

Some herpetologists still only recognize only one species - Charina bottae, with either no subspecies or with two subspecies -

C. b bottae - Northern Rubber Boa

C. b umbratica - Southern Rubber Boa.

Others recognize two full species of Charina, as is done by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the SSAR, the CNAH, and this web site -

Charina bottae - Northern Rubber Boa

Charina umbratica - Southern Rubber Boa

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

IUCN Charina bottae Taxonomy Notes

Published in 2007.

Accessed 1/10/15

"Nussbaum and Hoyer (1974) showed that subspecies utahensis is indistinguishable from subspecies bottae, and they regarded the concept "umbratica" as meaningless; Collins (1990) apparently agreed with this view and did not recognize any subspecies. In contrast, Erwin (1974) proposed that subspecies umbratica warrants species status; this suggestion did not gain the support of other herpetologists. Stewart (1977) recognized two subspecies (bottae and umbratica) and, pending further study, regarded populations from Mt. Pinos and the Tehachapi Mountains, California, as intergrades between these two subspecies. Stebbins (1985) continued to recognize three subspecies (bottae, utahensis, and umbratica). Rodriguez-Robles et al. (2001) used mtDNA data to examine phylogeography of C. bottae and concluded that "C. b. umbratica is a genetically cohesive, allopatric taxon that is morphologically diagnosable" [using a suite of traits] and that "it is an independent evolutionary unit that should be recognized as a distinct species, Charina umbratica". The authors acknowledged that a mixture of bottae and umbratica traits exists in populations in the Tehachapi Mountains and Mount Pinos, but they interpreted this as persistent ancestral polymorphisms. They also found no support for recognizing utahensis as a valid taxon. Crother et al. (2003) listed C. umbratica as a species whereas Stebbins (2003) mentioned the proposal but did not adopt the split. In this database we maintain umbratica as a subspecies of C. bottae until a concensus on the taxonomy of this group emerges."

Notes from SSAR Herpetologican Circular No. 39, 2012:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Kluge (1993, Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 107: 293-351) placed Lichanura in the synonymy of Charina because they formed sister taxa. Burbrink (2005, Mol. Phylogenet. Evo. 34: 167-180) corroborated the relationship found by Kluge. However, Rodriguez-Robles et al. (2001, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 18:227-237) found C. b. umbratica to represent a morphologically distinct, allopatric lineage that they elevated to species status based on mitochondrial sequences, along with allozyme data from a previous study (Weisman, 1988, MS Thesis, CSU Polytechnic Pomona). With the recognition of C. umbratica and fossil species referred to both Charina and Lichanura (Holman, 2000, Fossil Snakes of north America, Indiana Univ. Press) neither genus is monotypic and they are treated here as separate genera."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

'The subspecific inclusion of C. b. umbratica necessitated the change in English name from “Northern Rubber Boa”. '

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Charina bottae bottae - Northern Rubber Boa (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Charina bottae - Northern Rubber Boa (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Charina bottae - Rubber Boa (Stebbins 2003)

Charina bottae bottae - Pacific Rubber Boa (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Charina bottae bottae - Pacific Rubber Snake (Rubber Boa) (Wright & Wright 1957)

Charina bottae bottae - Rubber Snake (Stebbins 1954)

Charina bottae bottae (Van Denburgh 1922)

Charina bottae - Rubber Snake (Tortrix Bottae; Charina brachyops; Charina plumbea; Pseudoeryx bottae. Two-headed Snake; Lead-colored Worm Snake; Wood Snake; Rubber Boa, part) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Charina bottae (Blainville 1835)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Boidae |

Boas and Pythons |

Gray, 1842 |

| Genus |

Charina |

Rubber Boas |

(Gray 1849) |

Species

|

bottae |

Northern Rubber Boa |

(Blainville, 1835) |

|

Original Description |

Charina bottae - (Blainville, 1835) - Nouv. Ann. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris, Vol. 4, p. 289, pl. 26, figs. 1, 1B

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Charina - Greek - charieis = graceful, delightful

bottae - honors Botta, Paolo E.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Snakes |

C. umbratica - Southern Rubber Boa

L. t. roseofusca - Coastal Rosy Boa

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Snakes of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bartlett, R. D. & Alan Tennant. Snakes of North America - Western Region. Gulf Publishing Co., 2000.

Brown, Philip R. A Field Guide to Snakes of California. Gulf Publishing Co., 1997.

Ernst, Carl H., Evelyn M. Ernst, & Robert M. Corker. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003.

Taylor, Emily. California Snakes and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2024.

Wright, Albert Hazen & Anna Allen Wright. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1957.

Brown et. al. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society,1995.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow,

Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

St. John, Alan D. Reptiles of the Northwest: Alaska to California; Rockies to the Coast. 2nd Edition - Revised & Updated. Lone Pine Publishing, 2021.

Mitochondrial DNA-Based Phylogeography of North American Rubber Boas, Charina bottae (Serpentes: Boidae)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Vol. 18, No. 2, February, pp. 227–237, 2001

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|